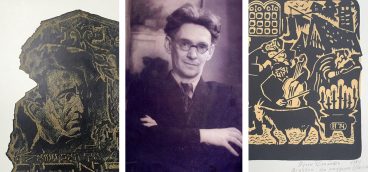

I can’t really say if I found Ernie, or if Ernie found me. When I volunteered for a writing project at the Pittsburgh Holocaust Center in 1992, he was the first person I met. An engaging, bespectacled gentleman in his early 70s, Ernie was one of about 200 Holocaust survivors living here at the time.

I never got to know the others. I just kept talking to Ernie. I liked him from the start, and eventually, our many conversations, first at the Holocaust Center and then at his home, led to a small book.

At 23, Ernie Light, a native of Chudlovo, Czechoslovakia, ended up at the gates of Auschwitz in May 1944. The youngest of 10 children, he arrived at the infamous Nazi concentration camp stuffed inside a locked cattle car along with his mother, father, a brother with polio, a sister with her child, and about 80 others.

During the 24-hour train ride, everyone was squeezed in so tightly that it was impossible to sit, unless you sat on one another. There was no bathroom. At Auschwitz, the cattle car doors swung open, and German guards screamed “Out, out, fast, fast!” The children, many of whom had been crying, clung to their mothers’ dresses.

Eventually, Ernie was sent in one direction, while the rest of his family was herded elsewhere. The next morning Ernie found himself in a huge courtyard with thousands of other prisoners surrounded by electric-wire fencing and guards in towers with machine guns.

Ernie’s main thought was: “Where are my parents, brother, and sister and her child?’ Finally, someone, who had been at Auschwitz a few days, pointed to a building in the distance. “You see that smoke?” the man said. “You smell that stench? That’s where your family is.”

The idea of a crematorium was beyond his comprehension and at first, he was in denial that five beloved family members could be gone just like that. He was frozen in time.

He remembered thinking, “Why?… It’s impossible… How can you take children and gas them and burn them?”

* * *

I met with Ernie on Sunday mornings, prepared with dozens of questions. Ernie had a warm smile and always seemed upbeat. As head of the Pittsburgh Holocaust Center Speakers Bureau, he was used to tough questions concerning his past. Each week, he visited schools and churches to talk about the Holocaust, how he survived, the evils of intolerance, and the importance of speaking out when wrongs are done to others. He would end each of his speaking engagements with a question-and-answer session.

After about a half-year of interviews, I had enough material to put his first-person account into print. In the little book, Ernie discussed growing up in a community of mostly Christians and 18 Jewish families, where everyone got along and anti-Semitism was virtually non-existent. His father owned farmland, and one of his best friends was the son of a Greek Catholic priest.

In a very short period, it all changed. He recalled July 1944 and staggering through an 80-mile death march—from Warsaw to Kutno, Poland—in exceptionally hot weather with nothing to drink. Those who stopped or lagged were shot.

Thirst was worse than hunger. He described the feeling of lice crawling all over his body and always being hungry. He recalled the once-a-month inspections at a work camp in Muhldorf, Germany, where he was paraded in front of SS officers. Everyone had to take his shirt off. Prisoners deemed too frail by the SS were taken to the gas chambers at nearby Dachau.

Ernie almost lost the will to live and, at one point, gave up on God. He told the story of a fellow prisoner who threw himself in front of a passenger train to commit suicide. And he spoke of the day he found a small piece of bread on a dead prisoner, lying in the bunk next to him, and quickly ate it.

Ernie weighed 155 pounds when World War II started. When U.S. medics found him in May 1945, he weighed less than 80. He had stared death in the face and survived.

* * *

With the writing completed, I showed up at Ernie’s house, looking for pictures we could put in the book. As I waited for him at a dining room table, he went upstairs to search for photos. I noticed a dozen or so letters taken out of a large manila envelope. They were from students at a school Ernie had recently visited, thanking him for coming.

One read: “Dear Mr. Light, I greatly appreciate your coming to our school to tell your story. I know I am part of the last generation that will get to hear survivors and still ask questions.”

When Ernie returned with pictures, I asked, “Do you have more letters like these?” He said he did and that he kept them in shoeboxes. He returned with several shoeboxes, containing hundreds of letters, thanking him for speaking at schools, churches, social clubs and other places throughout Western Pennsylvania.

One read: “Dear Mr. Light, My whole life I have not known all the pain and suffering of my family’s past. Half my family is Jewish and many of my relatives died in the Holocaust. The subject was so threatening to my family that the topic has been avoided for my whole life. Thank you for having the courage that my family lacked to be able to talk about this. You have enlightened me of my past.”

Another: “Dear Mr. Light, You answered the students’ questions with patience and gentleness. Your answer to one student’s question about God will long remain with me. I believe it was important for the students to hear you affirm your faith in God and make the distinctions between the actions of man and God.”

Ernie became a Holocaust speaker after attending a reunion of survivors in Jerusalem in 1981. When he returned home, he said, “the realization struck him that he had to start talking about it.” It was time.

After going through Ernie’s many letters, the idea struck me to add another chapter to the book—“Letters to Ernie.” Then, for some reason, I posed another question: “Ernie, with all these letters, is there one of them that’s your favorite?”

Without hesitation, he said there was. “I keep it upstairs, near my bed, in its own envelope. Do you want to see it?”

“Yes,” I answered. “Could I?”

And so, I waited at the dining room table for Ernie to bring down this cherished letter.

During the many Sunday mornings I had spent with him, our conversations had run the gamut from unimaginable dastardly acts to emotional reunions with relatives who also survived. And finally, there was a story of triumph.

Arriving in the U.S. in 1946 with very little, Ernie and two of his brothers eventually became successful business owners (Light Brothers Clothing Store in the Uptown section of Pittsburgh, 1950–92). Ernie married, had two daughters and was blessed with four grandchildren. He certainly was someone who didn’t take life for granted, and when asked about the Holocaust or other matters, his answers were always well considered. So, I wondered, what did this one letter contain, what did it touch upon, that made it his favorite? What was so special about this letter that he kept it in its own envelope, while all the others went into shoeboxes?

Ernie came down the steps and handed me the envelope. I opened it and took out the letter. The first thing I noticed was that it was very short: “Dear Mr. Light, I am very sorry that I fell asleep when you spoke to our class. When I was awake, you were very good.”

I looked up and Ernie was wearing a wide smile.

“Ernie, this is your favorite letter?”

“Yes,” he answered. “That’s my favorite. It’s a good letter.”

* * *

Ernie lived to be 91, passing away four years ago, in November 2011. The small spiral-bound book—“Ernie’s Story: Surviving the Holocaust”—did end up containing a last chapter of “Letters to Ernie.” I did not include his “favorite” letter, however. We printed 300 copies, and the plan was for Ernie to leave a book at each of his speaking engagements. Hopefully, a few people took the time to read it.

Back in the 1950s and 1960s when I was a student, Holocaust education was limited or non-existent at the elementary, junior high and high school I attended. At that point, I don’t think the history books covered it much. I’m well aware that each survivor’s story is different and that circumstances differed in each country where Hitler and the Nazis sought the elimination of the Jews and others deemed undesirable. But, I don’t think I could have found a better person to learn from than Ernie.

Ernie became a Holocaust speaker after attending a reunion of survivors in Jerusalem in 1981. When he returned home, he said, “the realization struck him that he had to start talking about it.” It was time. At first, Ernie said, he was nervous and uncomfortable speaking in front of groups. But he kept talking and kept improving. As the years went by, many of the questions he received from school children, after his talks, were asked over and over again: “Why didn’t you run away? Why didn’t you try to escape from the concentration camps?”

There were, however, those “unexpected and interesting questions,” where Ernie had to dig deep to find the right words and the right answer. Once, after speaking at Pittsburgh’s Schenley High School, he was asked, “With all the suffering you went through, after the liberation, why did you remain Jewish?”

“The boy that asked me the question was black,” Ernie told me. “And, I couldn’t help but wonder if he thought: ‘You are white. You could have blended in. My people never had that option.’ I told the class at Schenley that, if anything, my experience has strengthened my identity. At least I know who I am. When the war began, the Jews who converted to Christianity or assimilated were still Jews in the eyes of Hitler. He took them with the rest of the Jews. Most of them were really lost souls.”

Of all the subjects that I touched upon with Ernie, the one that seemed to baffle him the most was Holocaust deniers. He said that one time he was speaking at a junior high and during the question-and-answer session, a boy asked him: “Why are there Holocaust deniers—people who say it never took place?”

Ernie said he told the boy, “During every period in history there have been people who have tried to rewrite history to their needs. I think the ones saying the Holocaust never happened are obviously anti-Semitic. But why they continue to deny it happened, I don’t know.”

Ernie later told me, “I really don’t think I gave the boy the best answer. That was a tough question. I’m still working on it.”

I guess to some extent, I’m in the same boat. After all these years, I still ponder why his most cherished letter was from someone who fell asleep while he was speaking. Was it his favorite because he thought it was funny? Perhaps he really did think it was a good letter. Maybe, he kept it separate from the others to remind himself of how special each and every child is—even the ones dozing off and not listening. I don’t have the best answer. I’m still working on it.