The motto painted on the wall of Chautauqua Institution’s outdoor amphitheater exhorts the audience to “Share Your Light.” It’s a message that Chautauquans take seriously, returning annually to the lakeshore community to debate, learn and generally immerse themselves in ethics, arts, music and current events. But as the lakeside institution just over the New York border celebrates its 140th year, it may have to spread the illumination a bit more broadly.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”88″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

The institution has long been a bond among a select audience, many of them Pittsburghers. But this year’s name-check from Smithsonian magazine, which made Chautauqua the first choice of its “best small towns to visit in 2014,” suggests that its brand of brainy conversation and bucolic location is broadening its appeal, despite the digital barrage of likes, tweets and reality TV.

“I call it a liberal arts college for grown-ups,” quips Sherra Babcock, the institution’s vice president for education. Over 100,000 people attend the nonprofit’s programs during its nine-week season, including 8,000 pre-professionals who enroll in summer schools for art, music, dance, theater, writing skills and other special interests.

In its breadth of offerings, Chautauqua differs from other well-known contemporary programs, such as Tanglewood, focused exclusively on music, or the Aspen Seminars, an extension of the Washington think tank. But it was an influential force in 19th century America, lending its name to similar gatherings of devout and earnest scholars who sought to spread enlightenment.

Founded in 1874 as a lakeside Protestant Sunday school assembly, the institution retains a tradition of self-improvement, but it has loosened its stays. Theater, discouraged in the 19th century, has become a mainstay of its entertainment program, along with opera and music. A prohibition on alcohol was finally lifted in 2007. Its fin-de-siècle public buildings are now wired for Wi-Fi. And in recent years, Chautauqua has begun to celebrate contemporary American fiction and non-fiction with its own book award. Timothy Egan was honored in 2013 for “The Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher,” his account of the early 20th century photographer Edward Curtis, who created portraits of 80 American Indian tribes.

The three-year-old Chautauqua Prize is a natural extension of an emphasis on reading and writing that has been a feature of the program since 1878, when co-founder John Vincent compiled a list of titles that readers could follow for self-improvement. The Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle now claims to be the nation’s oldest book club, a year-round correspondence program with chapters still operating in Zimbabwe and Nagasaki. Over 10,000 graduates have completed four-year programs, and graduation ceremonies are held on the grounds each August. An active program for young readers selects titles that encourage age-appropriate discussion.

As Babcock notes, the current focus accents not only literary content, but also the writing process itself. This year’s Writers’ Festival, June 12 to 15, invites aspiring authors to workshop their compositions with experts.

Distinguished authors are weekly visitors to the regular summer program. The acerbic memoirist and Time magazine contributor, Roger Rosenblatt, kicks off this year’s lineup on June 26, followed by novelist Christopher Wakling, political philosopher Danielle Allen, poet Frank X Walker, National Book Award winner E.L. Doctorow, anthropologist John Colman Wood and physician-reporter Sheri Fink.

As in past seasons, the writers’ appearances are tied to themes addressed in daily lectures in the open-air amphitheater. Rosenblatt’s visit is part of a weeklong emphasis on storytelling from the viewpoint of guests such as Tom Brokaw and Margaret Atwood. Walker will read from a new collection that reimagines the experience of York, the African American member of the Lewis and Clark expedition, during a week devoted to an examination of westward expansion. (In a nod to the Twitterverse, audience members may submit questions to lecturers via tweets, an innovation adopted last year.)

The exploration of the West is also the subject of a collaboration among the institution’s schools of theater, voice, opera, dance and visual arts. “Go West!” marks the second season of a multidisciplinary arts production that culminates in a 300-person performance on July 26. Young members of resident performing troupes such as the North Carolina Dance Theater or scholarship students in other disciplines will participate in the Inter-Arts Collaboration, which is unique among American arts summer schools.

The marquee programs represent only a fraction of the classes at Chautauqua. Over 300 special studies courses, ranging from plein air painting to portfolio management to cryptography for kids, are offered each week of the season.

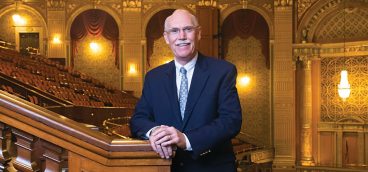

Vice President and Chief Marketing Officer George Murphy says that the curiosity for lifelong learning is what defines a Chautauquan.

“People don’t come here to do nothing,” he says. “They really want to interact with others.” That doesn’t mean that intellectual exchange is the only recreation. Golfing at Chautauqua’s two 18-hole courses, tennis, sailing, swimming and other sports provide the mens-sana element that its founders envisioned.

Chautauqua, which first introduced its audience to Islam in an 1898 course, has long prided itself on its global perspective. Two of this season’s spotlights are on Brazil as a rising superpower and the challenge of democracy in Egypt. In recent years, it has also chosen books and speakers that tackle political and religious controversy head-on.

Brian Castner’s “The Long Walk,” a searing and occasionally scatological account of the author’s service leading an I.E.D. (improvised explosive device) unit in the Middle East, was chosen for discussion in the Circle’s year-round book club (the group meets online to share opinions). Another unexpected title was “Children of Dust: A Portrait of a Muslim as a Young Man.” Ali Eteraz’s cheeky memoir, tracing his evolution from Pakistani madrassa student to contemporary American, confronted Circle readers with the complexities of Islamic heritage.

“We choose books that our volunteer readers feel ought to be read in order to achieve character,” says Babcock. “But we find that whatever the language or subject, our people are open-minded about books.”

This summer the institution’s weekly themes include prescient topics. The July 7–11 focus on the ethics of privacy was selected months ago, even before headlines on the NSA and Edward Snowden dominated the news. The global food supply, the June 30-July 4 theme, is also the topic of a yearlong magazine series by National Geographic, which has signed on as an institution partner for the subject.

United States history, a recurrent theme over past Chautauqua seasons, returns with a weeklong visit from documentarian Ken Burns. It’s an appropriate focus for an organization with a uniquely all-American past.