Is Pittsburgh Still a Baseball Town?

There has been a great deal written about the demise of baseball as America’s game. After the excitement of last season’s NFL playoff games and the drama of the Super Bowl, sports commentators, lamenting painfully slow and dull baseball games dominated by batters swinging with uppercuts and striking out at a record pace, decided to bury baseball and praise football as America’s game.

It’s a view that would find little disagreement among Pittsburgh sports fans. These days Pittsburgh, whether the Steelers win or lose, is a football town, and most Pittsburghers believe that football is our national game, if not our national religion. Those who still believe that Pittsburgh is a baseball town belong on the endangered species list, their numbers shrinking with each losing season. The only sport connected with baseball that’s growing in numbers these days is hating the Pirates owner.

I had the good fortune of growing up in Pittsburgh, a city with a National League baseball team and an NFL football team, so, at an early age, I became both an avid Pirates fan and an avid Steelers fan. In 1979, I actually experienced the joy of watching my Pirates win the World Series and my Steelers go on to win the Super Bowl and wondering, at the time, which victory meant more to me.

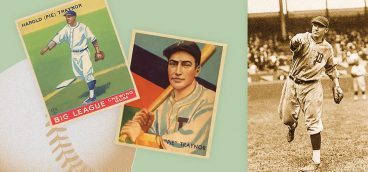

Thanks to my father, my first love was the Pirates. I remember my father telling me stories about Honus Wagner and Pie Traynor while we tossed a baseball back and forth and taking me out to Forbes Field for my first Pirates game in 1948 when I was nine years old. I don’t, however, recall my father teaching me how to throw a tight spiral while talking about Johnny Blood and Whizzer White or taking me out to Forbes Field for my first Steelers game. My love for the Steelers came a bit later when I watched the Black-and-Gold play their away games on black-and-white television in the 1950s. But, like my love for the Pirates, it was love at first sight.

On Sundays, with a lunch that my mother packed with chipped ham “sammiches,” I headed out to Forbes Field from my home on the working-class South Side, and, for a buck, sat on a bench in the left-field bleachers, and watched a Pirates double header. I’d get there about noon, watch batting and fielding practice, then two games, the first starting at 1:00 p.m., the second sometimes lasting until 7 p.m, when it was suspended because of Pennsylvania’ s 7 p.m. Sunday curfew. I really didn’t care if I never got back.

It took a while before I started going out to Forbes Field to watch the Steelers, but, once I did, I never spent a dime to see them play. Early Sunday morning, I headed out to Forbes Field with my football buddies. Once we got there, we propped a Schenley Park bench against the right-field wall, climbed up to the top of the wall, where, carefully avoiding the barbed wire, we jumped into the right field stands. To avoid ushers, we found a hiding place under the right-field stands until the paying customers, wearing their Sunday finery, entered the ballpark. Nobody wore Steelers regalia in those days, unless it was a button.

I may have worshipped those Pirate and Steeler teams of the 1950s, but they were among the worst teams in professional sports. From 1950 through 1957, both teams fell short of winning records, though the Steelers did manage .500 seasons in two of those years.

The Pirates had three straight seasons of 100 or more losses in the early 1950s and, in 1952, finished at 42-112, the worst record in modern franchise history. I saw infielders who should have worn their gloves on their shins, outfielders who played fly balls on a bounce, and a Heisman winning catcher, who could catch a punt but couldn’t catch a pop foul. I saw bonus babies who should have given the bonus money back and grizzled veterans who should have been playing in Old Timers games.

The Steelers weren’t much better, but they did have a bruising defense led by Ernie Stautner, Jack Butler, and Dale Dodrill. Other teams, though they knew that they’d likely win, dreaded coming to Pittsburgh because of the beating they would take. The Steelers’ problem was their offense. The dull and unimaginative Steelers were the last team in the NFL to use the single wing . Their “three yards and a cloud of dust” offense was so predictable that Steeler fans yelled, “Hi diddle diddle Rogel up the middle,” when the Steelers came out of the huddle. They did draft great college quarterbacks, but either converted them into defensive backs (Joe Gasparella), traded them (Lenny Dawson) or dumped them (John Unitas) because they thought that they were too dumb.

The Steelers came to life in the late 1950s and early 1960s when the flamboyant Bobby Layne came to town, but the best they could do was the short-lived Playoff Bowl in 1962. Their long-suffering fans became increasingly restless and even a stalwart like Ernie Stautner wanted out: “This is a lousy sports town and if Art Rooney had any sense, he’d get out of it.”

The Pirates, on the other hand, became, for one glorious season, the stuff of dreams. In 1960, as fans flocked out to Forbes field. they gave Pirate fans, not just a winning season, but a World Series championship. I remember walking to work at Gimbels in Downtown Pittsburgh the morning after Mazeroski hit his miraculous home run. All around me was the litter that remained on the streets, but, for one day, I might as well been that nine -year-old kid again strolling my way to Forbes Field.

The Steelers, after faltering for another decade, finally gave Pittsburgh an NFL championship in the 1970s, and by the end of the decade had won four Super Bowls. The Pirates wove their own magic and won World Series at the beginning and end of the decade, and even Pitt joined in by winning a national football championship. The only problem was that I had taken a teaching position in the English Department at Southern Illinois University in 1969 and was living my life as a Pittsburgh sports fan in exile.

So there I was, walking the dog in southern Illinois after watching, on television, the Steelers defeat the Rams and wondering which was more important to me, the Super Bowl or the World Series victory. And as much as I was thrilled with the Steelers’ Super Bowl win I’d just watched, I knew, looking back on the 1979 season, that the Pirates winning the World Series meant more to me. I love the Steelers, but my heart belongs to the Prates.

In the years ahead, while the Steelers played in more Super Bowls and Steeler fans became the Steelers Nation, the Pirates nearly left the city twice, suffered Sid Bream’s slide in between, and, became the Titanic of baseball when they launched a 20-year losing streak. The Steelers play to sell-out crowds, while the Pirates could give tickets away on most nights and not fill PNC Park. So, I asked myself, why do I care more about the Pirates than the Steelers, no matter how bad the Pirates have been in recent years. And why do I believe Pittsburgh is still a baseball town?

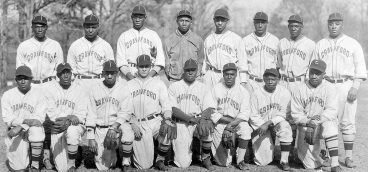

I think that the answer has as much to do with the game itself as my childhood memories. Baseball remains my favorite game, and, I believe, is still America’s game, because it has a history, dating back to the 19th century, that is far richer than any other sport. including football.

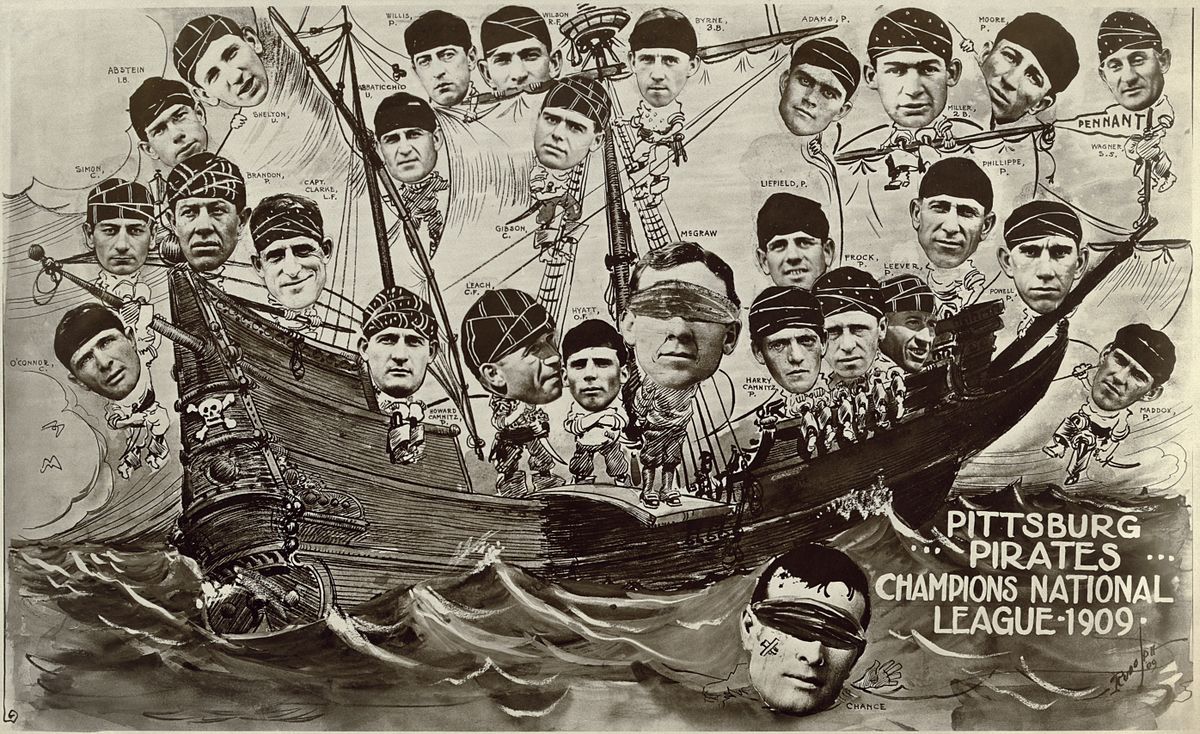

As for the Pirates’ own history, by the time the Steelers (called the Pirates at the time) came into existence in 1933 the Pirates franchise already had a glorious past. They played in baseball’s first modern World Series in 1903. In 1909, led by Honus Wagner, they won their first World Series when they defeated Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers, and, in 1925, they became the first team to come back from a 3-1 deficit in the World Series when they defeated Walter Johnson and the Washington Senators.

As for today’s seemingly hapless and hopeless Pirates, they are a reminder that while baseball can sometimes be a field of dreams, more often than not it breaks our hearts. Former Yale scholar and baseball commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti wrote that “baseball is designed to break your heart. You count on it, rely on it, but when you need it the most it stops.” Win or lose, and mostly these days our Pirates lose, we can always wait, even if broken-hearted, until next year.

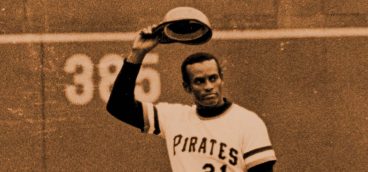

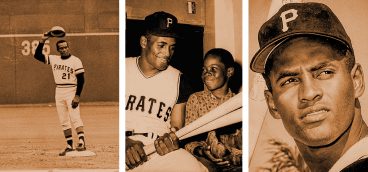

We are approaching the 50th anniversary of one of baseball’s most heartbreaking stories — the death of the hero at the height of his glory. In the 1972 season, in his last time at bat in the regular season, Roberto Clemente lined a double into the left-center field gap. It was his 3,000 hit, a feat rarely accomplished by a major league batter.

Led by Clemente, the Pirates had won the World Series in 1971 and were expected to repeat, but they suffered a heartbreaking loss on a wild pitch to the Red in the 1972 playoffs. The Pirates, however, still had the great Clemente and there was always next year.

But all that changed forever when Clemente, on a plane filled with relief supplies for victims of an earthquake in Nicaragua, died on New Year’s Eve when the plane crashed into the sea.

It breaks your heart.