Here’s to You, Mrs. Henderson

Of all of the thousands of students attending classes at the University of Pittsburgh last fall, Elsie Henderson was perhaps the most extraordinary. For starters, she didn’t walk the Oakland campus with an iPod fixed to her ears or consumed in cell phone conversation.

She doesn’t own either of those technologies. She doesn’t even own a computer. And she studied French not as a degree requirement, but because knowing the language might better inform her cooking.

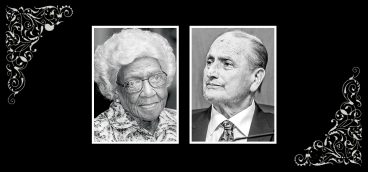

Mostly, though, it was her life experience that set her apart from the rest of the student body. Henderson is 94 years young and even at a school that offers a seniors’ education program, that is pushing the envelope. What is more, this youngest of 14 children from an African American family whose father died young bridged the chasm between her Mount Washington working-class neighborhood and the magnificent Fallingwater, lush country estates and seaside residences of such American royals as the Kaufmanns, Mellons, Heinzes, Shrivers and Kennedys.

Cook, baker, meal planner — she was hired help with an edge forged from a childhood spent in a time and place where nothing was taken for granted, and racism and segregation followed her like a shadow. Listen to her account of her journey across two worlds, and it is clear that what her wealthy employers got for their money was a devoted, hard-working woman with uncommon skill and instinct in the kitchen and the moxie to speak her mind when necessary and to demand respect always.

She shared some of those memories with Pittsburgh Quarterly one April morning. The conversation took place in her Highland Park apartment, across a dining room table she had already prepared for lunch with a single china setting, silverware and linen napkin perfectly arranged and as elegant a place setting as you’d find in any fine restaurant. It’s a habit that would’ve been an inconceivable extravagance in the neighborhood of her childhood with its muddy lanes and tight blue-collar row houses.

Elsie’s family managed to get by largely because of her mother’s simple rule: Everyone works. Several brothers had jobs in the local steel works. Her mother did housework for others. The only child not holding down a paying job, it seems, was Elsie herself. “I was more interested in school. I had a library card by the time I was six and I used it.” Her formal schooling ended with the 11th grade, but her love of the printed word, particularly poetry, and her intellectual curiosity did not. The payoff was an awareness of the world around her that belied her level of education. Whether it was Frank Lloyd Wright or Isaac Stern, she understood the significance of her employers’ guests and the issues they discussed better than most of the help.

Once, she recalls, the woman who hired her to cook for a party at her Sewickley Heights estate was nearly breathless with anxiety over the fact that a priceless dinner service would be used that evening. “There was a man in Sewickley who the rich people depended on if they didn’t have their own butler. The night this woman was having that big to-do she came out into the pantry and she said, ‘William, I want you to be very careful because the dinner service we are using belonged to the Emperor Napoleon when he was exiled on the island of Elba.’ And of course William, being a Southerner and not knowing much about history, said, ‘Island of what?’”

This has Elsie in stitches. “Oh, dear. I knew about Napoleon and Elba. But William, he didn’t get it. He said to her,‘If I break anything I’ll tell you.’ She said, ‘William, if you break one of these dishes, I love you dearly, but I’ll stop speaking to you altogether.’”

Life taught her other lessons, particularly what it meant to be black in America before civil rights became a movement. Trips taken as a child to segregated Front Royal, Va., to visit her grandparents in the 1920s cast lasting memories. “My grandparents were as high as black people could go at that time. My grandfather had a store that sold farm implements and had cattle. Not many white people came into his store, but everyone knew Bird Jeffries.

“At the end of their road, there was a white man who had a grocery store. And he had — I know it was homemade — the best peach ice cream. My grandmother would let us go down there, but she would school us first. She said, ‘When you go in, you give the man your money first. White folks don’t have to pay until after they get what they went there for. But you have to pay first.’ We’d do exactly as she said. ‘And when you come back up the road, don’t pass any white folks,’ she said. And she would get up and she’d show us what to do. ‘You step aside for them,’ she said. I didn’t think much about that back then. Little children, things go in one ear and out the other. And we did what we were told. But when I think about that now, it almost brings tears to my eyes. Could you see me stepping out in the road for someone today?”

The answer to that question is no. And from the stories she tells, it seems likely that those she worked for and who knew her well would also have a difficult time imagining her bowing to disrespect. Take her job interview with H.J. “Jack” Heinz II, for example. She had quit Schenley High School a year earlier to start cooking in Sewickley Heights. One day, Miss Gouzie, a white woman who paired wealthy clients with butlers, cooks and other help, called with a job lead.

Elsie arrived at the interview early to make sure the prominent industrialist was not kept waiting. “Finally, Mr. Heinz came in. He sauntered. He never walked. And we talked, and then he said, ‘If you come to Rosemont Farm, I promise you’ll have a good time.’ That didn’t sound right to me. It angered me a little bit. So, I said, ‘Mr. Heinz, if you give me ample time off, I’ll find my own pleasure.’ He left with his chauffeur and after he’d gone, Miss Gouzie said, ‘Elsie, you shouldn’t have said that to Mr. Heinz.’ I said, ‘Mr. Heinz shouldn’t have said that to me. I’m not going out there for a good time. I’m going out there to cook.’”

She did most of the cooking and baking at the Heinz estate, relying on skills learned from her mother or developed on her own, on the fly. “My mother kept open house,” Elsie says. “She wasn’t happy unless she was feeding people, so I learned a lot about cooking, most everything. Of course, there was a limit to the kinds of food we ate compared to what millionaires ate. But if you’re interested in those things, it comes easy.”

Pheasant was one of those foods, although at Rosemont Farm the job of roasting it fell to a chef hired specifically for the meat course. “When we had pheasant, he would remove the feathers to roast it, of course. But after it was roasted, he would clean those feathers and reapply them on the pheasant so when it was wheeled into the dining room, you just couldn’t believe it. It looked like the bird. Then, he would remove the feathers in front of the guests and carve.”

She left Rosemont Farm shortly after Jack Heinz and his wife, the former Joan Diehl, divorced in 1942, but not before spending three years with the family that she ranks among the most enjoyable of her career. The couple’s only child, the late U.S. Sen. H. John Heinz III, was five years old when they met and to this day she refers to the angel food cake recipe of hers that was his favorite as “Johnny Heinz’s chocolate mint angel food cake.”

Her longest and most memorable job was as a cook and baker for Pittsburgh retail mogul Edgar J. Kaufmann and his wife, Liliane, at their Fayette County summer home, Fallingwater, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright at the height of hiscreativity in the late 1930s. From 1947 to 1964, Elsie’s weekends at Fallingwater introduced her to some of the nation’s most famous writers, painters, opera singers, industrialists and politicians. They dined on cuisine she helped to prepare but had never experienced in her mother’s kitchen, including sweetbreads, standing ribs, roast pheasant, vichyssoise, cold jellied consommé, oyster bisque, Eggs Benedict, Yorkshire pudding, gazpacho and chocolate soufflé.

“Out of all of the people I worked for, the Kaufmanns were a head above everyone when it came to food. One thing about them was that they would not touch a leftover no matter what it was. The help would use it up, so it wasn’t wasted.”

In 1956, an August flash flood sent the waters of Bear Run over the parapet walls and into the famous house, damaging stairs and partially submerging the living room sofas. Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., “Young Kaufmann” to Elsie, had Wright flown in to supervise renovations and assigned her to greet him at Greater Pittsburgh Airport. She found the architect kind and engaging, if somewhat of a flirt. “Mr. Wright got into the car and said, ‘Young lady, what do you do at Fallingwater?’ I told him and he said, ‘If the food is as good as you look, everything will be just fine.’ On the ride back, he wanted to drive past the Cathedral of Learning, which he called the ugliest building in the world. I said, ‘Mr. Wright, everything in Oakland has taken up all of the space. The only way they could have gone was vertical.’ He said, ‘Yes, well, it’s still ugly.’”

The list of influential families she worked for grew as years passed. She spent several summers in Hyannisport, Mass. cooking for the Shrivers and Kennedys. Ethel Kennedy’s concern for and loyalty to her staff was legendary, Elsie says. When, for example, a long-time cook whose health was failing told the family she had to quit and move into a nursing home, “Ethel said, ‘No, when you die, you will die in my house.’ That is exactly what happened. And Ethel brought all of her people into Boston and put them up in a hotel for the funeral and Ethel’s sons were pall bearers.”

Ted Kennedy was another of Elsie’s favorites.

“One night, he was invited to stay for dinner. The Kennedys used leftovers, of course, and Ethel wanted the roast beef from the night before ground up and used with spinach and egg. Ted came in and was standing at the stove and I said, ‘Are you going to be with us tonight?’ He said, ‘What are we having?’ I showed him.” Elsie is giggling now, making a squinting face. “And he looked and looked and, oh dear, he said, ‘No, I don’t think so. I don’t eat anything ground up.’”

Those days are behind Elsie Henderson now. Most of those she worked for are long dead, as are many relatives and old friends. That is not to say she is inactive or that her ties to the region’s influential families have atrophied. Only a few months ago, a few of those families helped to secure her lease for at least another year when rent was raised far above her means.

With her housing concerns behind her, she’s focused on new projects, including a book of recipes written with former Pittsburgh Post-Gazette food editor Suzanne Martinson that is due out soon. And she expects to resume the study of French at the University of Pittsburgh in the fall, when, once again, she will be among the most extraordinary students on campus.