In this season of Steelers discontent, Gary Pomerantz offers rattled fans some balm. “Their Life’s Work” is a thoroughly reported and clearly written account of the Steelers’ sensational ’70s, framed through the “brotherhood” of the players and their interplay with the owners.

Based on more than 250 interviews over three years, Pomerantz retells the Steelers story that transcends mere athletics: how a once-hapless team, led by a patient family that breeds loyalty, manhandled its way to four Super Bowl titles and served as civic Prozac to a city undone by industrial decline.

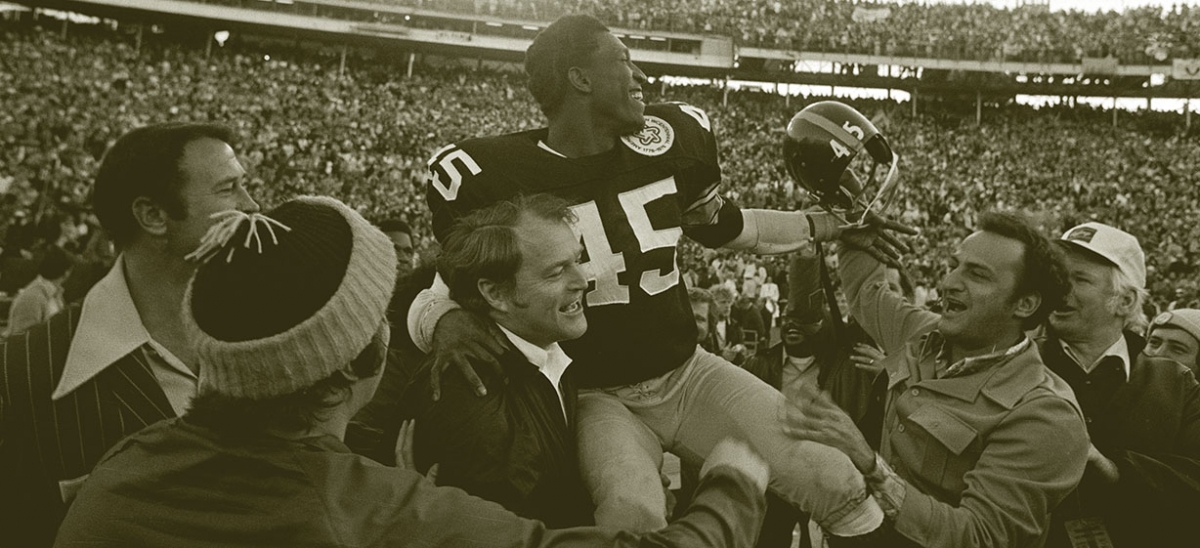

To its credit, “Their Life’s Work” ends up being two books in one. It first gives Steelers fans and casual observers alike what they need to revel in the glory of those days—from detailed coverage of the Immaculate Reception game in 1972 and the first Super Bowl triumph in 1975, to the pizzazz of Frenchy Fuqua’s platform shoes with goldfish in the heels and plenty of tough-jock quotes (“the sumbitch gets open and catches the football,” says one coach about Lynn Swann; “we kicked their asses very thoroughly,” says defensive end Dwight White about the Steel Curtain’s methodology).

But running through its 380 pages of text and 60 pages of notes and bibliography is another narrative: Football is rather unhealthy for its players.

“Football is a savage game,” declares Pomerantz, “a giant threshing machine that cuts down men in the physical prime of their lives.” For every stirring tale of a player’s rise from humble beginnings to the pinnacle of his profession, there is a cautionary tale of bodies wracked with lifelong post-retirement pain, and worse. Mike Webster’s descent into madness as a result of brain concussion gets a full chapter.

Pomerantz, a former Washington Post sportswriter who has written four other books and now teaches at Stanford University, is upfront about his ambivalence. “I saw the game from the inside and though I admired the athletic artistry and grace, and genuinely liked the men who played, the violence disturbed me,” he writes in the opening, explaining why he “gave up” on pro football by the late 1980s.

Lured back in the early 2010s, however, Pomerantz uses his journalistic storytelling skill to describe how the Steelers went from zeroes to heroes over the course of some hard decades. At times, the technique is reminiscent of historian Barbara Tuchman writing about the onset of World War I in “The Guns of August”: Everyone knows how the story is going to end, but as the details unfold, the suspense is gripping. While I have always loved to watch the Steelers play on Sundays, I take no interest in the strategies deployed off the field year-round. Yet Pomerantz’s explanation of scouting, recruiting and the draft—and especially the role of former Pittsburgh Courier journalist Bill Nunn Jr. in tapping into black colleges for key talent (e.g. receiver John Stallworth)—is compelling and convincing.

Real Steelers fans already know that the book’s title refers to coach Chuck Noll’s attitude toward players. Football is something they do for a decade or so, while preparing for “their life’s work.” (It was also used to cut players, as in “it’s time for you to get on with your life’s work.”) The phrase has a touch of irony as the book progresses and we see some players stumble through their post-football lives, though many fared quite well: Stallworth became a millionaire defense contractor; Joe Greene turned to coaching and then rejoined the Steelers; Franco Harris is a Pittsburgh living hero.

It’s not news to learn that Noll was highly professional as a coach and mighty reserved as a person, though Pomerantz shows his knack for an apt phrase by noting that Noll’s “door was always open, but his personality was closed.” By the end of the book, however, it seems that every player in Steelers history has gotten a chance to observe that Noll was emotionally distant; when the author himself notes in the final pages that “Noll wasn’t good at small talk or with sharing his emotions,” the football infraction of “piling on” comes to mind.

The undeniably great character of Art Rooney Sr.—the book’s lodestar—suffers a similar fate, I am sorry to say. The praise for his extreme modesty piles up to cloying proportions. “This was my kind of guy,” “Good people,” “I dig the guy to the utmost” is just a sampling from the players. “He’s God’s gift to the human race” writes a UPI columnist after the 1974 AFC title win. Even President Gerald Ford stands in awe of “The Chief” when the team visits the Oval Office after the first Super Bowl win. Pomerantz does acknowledge that the UPI writer was “every bit as fawning as most sports columns written about the Chief on this day,” but the parade of accolades he’s assembled turns into overkill.

The core of “Their Life’s Work” remains the personalities of the players and the indelible bonds they forged playing together on what fills Pittsburgh fans with irreplaceable pride: “We’ll never see another NFL team like these Steelers,” Pomerantz writes, blaming free agency and the salary cap. But those seem like mundane reasons in the face of the more cosmic case he’s built, brick by brick: that the 1970s Steelers—violent and eloquent, vicious and victorious, scrappy and sincere—were somehow destined to make us all believe in miracles.