Giving Thanks to Mosses

We hardly notice them. we trod all over them. Most mosses don’t even have universal common names. Moss experts are few. Yet mosses are among the most ancient of plants — the first to crawl out of the ocean and inhabit land 450 million years ago.

I wonder if that’s why I feel as if I’m in an ancient land when surrounded by mosses?

Some 22,000 species of bryophytes — including mosses, liverworts and hornworts — exist on every continent on the planet, from the cold of the Arctic to the heat of the desert. The only place you can’t find mosses today is, ironically, in the ocean. Pennsylvania has about 580 species of bryophytes.

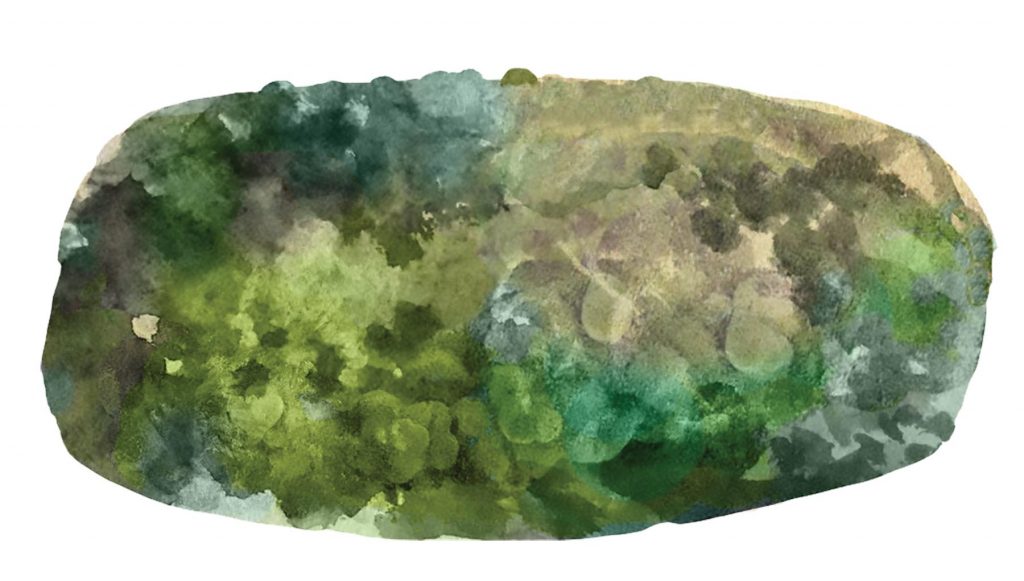

On my walks around the farm, I’ve always bent down and examined them — on the forest floor, by streams and hillsides — on rocks, logs, tree bark, and stumps. My own study of moss began by reading Robin Wall Kimmerer’s beautiful meditation, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses. A botanist, professor at SUNY and a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Kimmerer brings mosses alive by combining her scientific knowledge with Native American wisdom. “I want to tell the mosses’ story,” she writes, “since their voices are little heard and we have much to learn from them.”

Mosses are tiny, only a few centimeters tall, but they play a gigantic role in our ecosystem. They collect rain, prevent erosion, and provide habitat for small invertebrates such as water bears (or moss piglets), mites, spiders, and springtails. Mosses create seed beds for larger plants to take root, keep humidity in the air, and help heal land after fires and volcanos by spreading their spores onto scorched earth. We understand now, after years of harvesting moss from peat bogs — of which sphagnum moss is the largest component — that mosses store huge amounts of carbon and are crucial to stemming climate change. “There is more living carbon in sphagnum moss than in any other single genus on the planet,” Kimmerer writes.

The more I learned about mosses, the more I marveled at them. Mosses can regenerate from broken leaves or stems, clone themselves, and dry out by 98 percent and come back to life when rains return. With no vascular system, mosses absorb water through their leaves, and with no roots, attach themselves to surfaces with hair-like structures called rhizoids Mosses do not flower or fruit. Some are fluorescent; others, resistant to insecticides. Mosses have adapted by surviving where larger plants cannot. “Mosses can live in a great diversity of small micro communities where being large would be a disadvantage,” Kimmerer writes, such as “between the cracks of the sidewalk, on the branches of an oak, on the back of a beetle, or on the ledge of a cliff.”

Over the centuries, mosses have served humanity well. They’ve been used as insulation — in mittens, mattresses, cradles, cribs, and to chink cabins. When the 5,200-year-old “Iceman” was found in a Tyrolean glacier, his boots were packed with mosses, Kimmerer tells us. Mosses are absorbent — sphagnum moss also can absorb 20 times its weight in water — and were once used as diapers and menstrual pads. Mosses are simply beautiful.

I love it when mosses naturally cover my flowerpots and I’ve tried to encourage their growth with yogurt, but it is difficult. Some say to lather pots with a milkshake of moss and buttermilk, egg white, brewer’s yeast or even “a slurry of horse manure,” which I’ll try next, having a plethora of horse manure on the farm. I’ve tried transplanting mosses too, but not successfully. Rock-loving mosses are more difficult to transplant than soil-dwelling mosses, Kimmerer says, and moss must be moved to the “same conditions, the same kind of rock, light and humidity.” But in the end, she writes: “I wonder if it is a kind of homesickness. Mosses have an intense bond to their places that few contemporary humans can understand.”

In trying to identify mosses, I was missing a crucial piece of equipment: a jeweler’s loupe. I learned that straight away when I had the privilege of looking at mosses on the farm with Scott Schuette, a botanist and bryologist at the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. I led Schuette first to a corner of our driveway by a stone bridge to look at a moss I particularly liked because of its blue hue. The moss looked exotic to me, but it couldn’t have been more common — Bryum argenteum, the type nestled in the cracks of city sidewalks. Schuette retrieved his small microscope, handed it to me, and a whole new world erupted before my eyes. What had resembled a green carpet was suddenly a mass of green worms. What I had perceived as blue was actually a silver tinge on the moss’s transparent tips.

Schuette loves showing mosses to people, especially in autumn when, without the diversion of flower and color, mosses are easier to spot. Then, he said, people can go back into the woods in the depths of winter and look again because mosses are still green in an otherwise brown world. Most people don’t realize what they have in their own backyards, Schuette said, even in the city. “Their minds are blown. They say, ‘I had no idea.’ It’s great to show that to people; they slow down, take time, and look.”

We walked around the edge of the pond and came upon a moss that through the microscope looked like a miniature Christmas tree. Schuette called it pinetree or tree moss, but Robert Klips’s field guide, Common Mosses, Liverworts, and Lichens of Ohio, called it American tree moss — Climacium americanum. We were in its ideal habitat, on a pathway near water. I asked if walking on it harmed it, and Schuette said no, but walking on it does keep its growth at bay. Then we found Bryoandersonia illecebra, whose branches looked round under the microscope. Schuette called it worm moss, but the book called it spoonleaf moss.

We put our discoveries into small, brown paper bags and wrote the Latin names on top.

If mosses have benefited humans, how have we helped them? “There’s not a lot of conservation effort,” Schuette told me. “They aren’t charismatic like elephants or lions.”

Humans return the favor by collecting moss for commercial purposes — up to a million pounds a year moss buyers report, according to Penn State — for horticulture use and in arts and crafts. Forty-one percent of it is collected from Appalachia by “mossers,” an old Appalachian practice. We ship moss to 40 countries. Irresponsible harvesting threatens not only moss populations, such as lichen, fungi, and ferns. Creatures like salamanders are often harvested in the process. Schuette testified in a Pennsylvania moss-poaching case against a man in Central Pennsylvania accused of stealing 18 feed sacks of moss in a public forest. Rules exist about which mosses can be harvested, how and where, but Schuette prefers none be taken at all as businesses now exist that grow mosses commercially.

Most animals don’t eat mosses, Schuette said, because of low nutrition and phenolic compounds. “Mosses aren’t inedible; they’re just not delectable.” Reindeer, deer or bear might eat them, he said, but only when other food sources aren’t available, or when eating something else such as blueberries or cranberries. Kimmerer, however, tells the story of a bear that ate moss. The moss passed through the bear’s digestive track whole and Kimmerer wonders if bears purposely eat moss to avoid defecating during hibernation.

I thought we’d travel to the far reaches of the property, where for weeks I’d been making mental notes of mosses to show Schuette, but after an hour and a half we’d found so many mosses — a dozen species on just a few boulders — that we’d hardly moved from the pond. “A nice little microclimate,” he said. On the roof of my writing cottage Schuette identified Hedwigia ciliate, which Klips’s field guide confirmed is usually associated with boulders in the woods, but also “makes an appearance on old roof shingles.” On a rain barrel he showed me Hygroamblystegium varium, described in Klips’s book as “dainty” but offered no common name.

“That’s your first liverwort,” Schuette said to me, pointing out the fuzzy Ptilidium pulcherrimum — or naugehyde liverwort — on the stonewall around the riding ring. “A whole ecosystem potentially lives here,” he said, including centipedes, millipedes, ants, beetles, slugs, and snails. We found a moss I had wanted to show him — which I’d given the common name of fern moss because it looked like a cluster of tiny, squashed ferns — Thuidium delicatulum. Klips’s field guide allowed that “newcomers [such as myself] to botany can be forgiven for trying to look up delicate fern moss in a fern book.” We also found a moss that does have a universal common name: Polytrichum, “many hairs,” or haircap moss, widespread and common.

“What’s in a name?” Shakespeare asked. In the case of bryophytes, a whole lot of letters. Who can blame Kimmerer’s students for begging for shorter names so that mosses are easier to learn? How about memorizing this “mouthful of a name” as Schuette called a tiny liverwort — 1.5 mm wide that grows in bogs: Fuscocephaloziopsis loitlesbergeri. I was charmed by a moss we found that Schuette described as wearing a little stocking cap, so much easier to remember than Orthotrichum ohioense. Still, what fun I had bandying about our invented common names. Klips’s field guide called Dicranum scoparium little brooms, but I called it little troll hair, and Schuette called it “bad hair day” moss. No matter the name, what a magical, miniature world Schuette helped me discover under my feet.

At the end of Kimmerer’s book, she gives thanks to mosses for helping other plants and animals to flourish. Tree seedlings thank mosses for places to sprout; fungi for moisture; birds for nest-building materials; and insects for habitats for their larval stages. Now that I have met mosses, I give thanks to them too. “The patterns of reciprocity by which mosses bind together a forest community offers us a vision of what could be,” Kimmerer writes. “They take only the little that they need and give back in abundance.” She wishes humans would do the same.