Crime Is Dropping, but So Are Relations With Police

Editor’s note: This story was first published in the Spring 2020 issue of Pittsburgh Quarterly.

Southwestern Pennsylvania continues to be one of the safest metropolitan regions in the nation, and the latest data suggest it’s only getting safer.

The overall crime rate in the seven-county Pittsburgh Metropolitan Statistical Area stood at 1,687.7 per 100,000 residents in 2018, a year-over-year decrease of 9 percent, according to FBI Uniform Crime Report data. Only Boston had a lower overall crime rate among Pittsburgh Today benchmark regions.

“Compared to other regions, we look pretty good,” said Alfred Blumstein, a professor of urban systems at Carnegie Mellon University. “I think this story is largely a positive one for public safety in the city and in the Pittsburgh region.”

But local experts say the region still faces significant public safety challenges. “An important pressing concern is the issue of police community relations,” Blumstein said. “The notion of trust and faith between the community and the police is still nowhere near as good as we would like it to be.”

Crime at low tide

Southwestern Pennsylvania long has ranked among the lowest-crime regions in metro America. Seattle, for example, had the highest overall crime rate among Pittsburgh Today benchmark regions. At 3,690.3 crimes per 100,000 residents, its overall crime rate is nearly twice as high as what is reported in the Pittsburgh MSA.

Compared to southwestern Pennsylvania, Indianapolis has 1,597 more crimes per 100,000 residents, Baltimore reports 1,503 more crimes per 100,000 residents and Philadelphia reports 674. Even benchmark regions that enjoy rising popularity and populations can’t match Pittsburgh when it comes to low crime rates. Charlotte has 1,479 more crimes per 100,000 residents and Austin has 963.

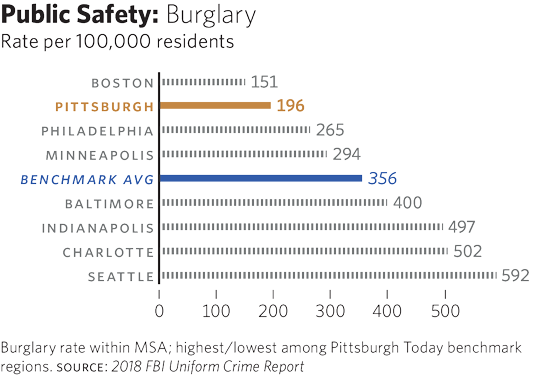

The Pittsburgh MSA did see increases in several categories of violent crime. The murder rate increased a hair from 5.4 to 5.5 per 100,000 residents, and the rate of forcible rape increased from 20.6 to 25.8. Motor vehicle theft and rates of aggravated assault also rose slightly. But even with the increases, the rates of rape, aggravated assault and car theft in southwestern Pennsylvania are lower than in any other benchmark region. And the Pittsburgh MSA saw significantly lower rates of other crimes, such as burglary, which fell by 23 percent.

The numbers follow many years of consistent declines in violent crime, both in Pittsburgh and across the nation. “We’re now at extremely low crime rates in comparison historically,” said Edward Mulvey, director of the Law and Psychiatry Program at the University of Pittsburgh.

As with all metros across the country, crime in the Pittsburgh MSA tends to be concentrated in and around urban areas.

Such neighborhoods often contend with longstanding regional problems, such as decades of shrinking populations and economies. More recent problems, such as the opioid epidemic, are not exclusive to cities, affecting suburban and rural communities alike.

Despite these entrenched issues, Pittsburgh’s crime rates are the envy of many other similarly sized MSAs. However, at the neighborhood level, new data suggest a persistent and widening gap in the degree of trust communities have in the police who serve them.

Challenging relationships

In Pittsburgh’s high-crime areas, relations between residents and local police have eroded over the last several years, community surveys carried out by the Washington, D.C.-based Urban Institute suggest.

Grading on a scale of 1 through 5, residents rated their “relatability to the police” an average of 2.9 in 2015. That rating fell to 2.6 in 2017. Their “willingness to partner with the police” rating dropped from 3.8 to 3.3, and their views of “police legitimacy” slipped from 2.9 to 2.7.

Using a combination of data from host police departments and public information, institute researchers and their community partners identified residential streets with the highest concentrations of poverty and violent crime, and then conducted public surveys measuring community perceptions of the police across a variety of topics. The surveys took place in two waves, one in late 2015, and another in 2017, with different respondents surveyed in each wave.

The surveys were done as part of the National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice, a multi-city collaboration between the U.S. Department of Justice and the John Jay College of Criminal Justice’s National Network for Safe Communities, the Center for Policing Equity and Yale Law School.

Trainings and interventions were developed to strengthen relationships between police and community members. Best practices, including implicit bias training for police and frameworks for community engagement, were rolled out in participating cities starting in 2015, including Pittsburgh. Other cities included Stockton, Calif.; Minneapolis, Minn.; Gary, Ind.; Fort Worth, Texas and Birmingham, Ala.

Pittsburgh is the only city in the initiative where every single metric for perceptions of the police and police-community relations got worse over the two-year period.

Some local experts say the data, although small, highlight longstanding tensions between local law enforcement and the wider community, especially in high-crime areas of the city.

“We deservedly can say we really went all in on that Justice Department training, but it wasn’t enough,” said David Harris, a professor of Law at the University of Pittsburgh. “I think equity and fair treatment continue to be an issue here, whether we want to recognize it or not.”

However, Mulvey said the numbers don’t do justice to the overall positive impact that a more community-oriented approach taken by police over the last several years has had. “It’s a short-term read on a long-term problem, and I don’t think it’s that informative, frankly.”

City police Commander Eric Holmes, the local liaison for the project, said the bureau considers their work with the initiative to be a success. In addition to bolstering longstanding community engagement programs, Pittsburgh has added procedural justice concepts, such as implicit bias trainings and evaluations of all officers. They developed intervention strategies for specific underserved communities, such as East African immigrants, and worked with the Department of Public Safety to develop a multicultural unit.

Holmes said he takes the community survey data seriously, but doesn’t find them surprising.

“Most of them, maybe all of them, were done in high crime areas, in neighborhoods where historically we’ve had a strained relationship, and the data shows that. We’re a work in progress as a police agency, and it just shows us that there’s more work to be done.”

Fragmented enforcement

Improving police-community relations in the region’s low income and high-crime areas is made all the more difficult by a longstanding characteristic of Allegheny County: the fragmentation of local governments and public services.

There are 109 separate police departments spread across the county. Within the City of Pittsburgh alone, the city police have overlapping jurisdiction with police departments from the six major universities as well as both UPMC and Allegheny Health Network hospitals.

In many former steel towns nearby, local tax bases are stretched thin, leaving little money for community engagement, enhanced accountability and other measures to help the officers policing them.

“We have all these departments with very little oversight, with the inability to do anything but some of the more basic tasks, taking on some of these big regional problems,” Harris said. “It’s simply not sustainable in a way that I think serves everybody and gives everybody good service.”

While Cheswick Borough and Springdale Township elected to combine their police departments earlier this year, similar efforts at police consolidations historically have been met with fierce resistance from local departments. “Having a metro police agency would be awesome,” Holmes said. “But I will be long retired before that would ever happen.”

He and other experts emphasize that public safety is a complex issue and that further improvements depend on addressing the many conditions in the region that influence crime.

“We have to think of a much more holistic approach. It can’t just be more cops, more arrests. That’s never the answer. I think we know that now,” Harris said. “Woe unto us if we don’t think more broadly and try to bring not just the necessary law enforcement, but the social services, the investment, the jobs. The underpinning of the community is what has to be repaired.”