Andrew Carnegie was America’s first great industrialist, the nation’s quintessential philanthropist, and, closer to home, Pittsburgh’s favorite son. He was also, however, a man of startling ethical and moral contrasts, and those paradoxes threaten his reputation.

Was his bountiful philanthropy based upon purely beatific instincts or was it, to paraphrase Clausewitz, simply self-promotion “by other means?”

During the “over busy 19th century,” as philosopher Hannah Arendt termed it, nobody was busier than Carnegie. He was born in 1835 in Dunfermline, Scotland, to William and Margaret Morrison Carnegie, both from long lines of political radicals and free thinkers. Their first child, Andrew, was born into modest but promising circumstances. Will Carnegie was a third-generation weaver. Unfortunately, his trade and the modest economic underpinnings of the family were in the crosshairs of the first stage of the industrial revolution: textiles. By 1835, there were 110,000 power looms in Great Britain, and each year tightened the economic vise until in 1847 a defeated Will Carnegie told his son: “Andra, I can get nae mair work.”

In 1848 the family immigrated to Pittsburgh’s North Side, then Allegheny City. Andrew had to find work. His first job as a bobbin boy at the Blackstock Cotton Mill paid $1.20 a week for a 12-hour day, six days a week. He soon became a messenger boy with the Atlantic & Ohio Telegraph Company at $2.50 per week. It was his first big step, and he knew it: “There was scarcely a minute in which I could not learn something… I felt that my foot was on the ladder and that I was bound to climb.”

While not out delivering messages, Carnegie began to sit in for the telegraph operators and quickly learned the trade. In 1851 he was promoted to fulltime operator at a salary of $4 a week. With his astounding telegraphy skills and willingness to take on managerial duties, Carnegie’s profile began to rise. This was not without design: “The rising man must do something exceptional and beyond the range of his special department. He must attract ATTENTION.”

He drew the notice of Tom Scott, superintendent of the western division of the Pennsylvania Railroad and became Scott’s telegraph operator in 1853. One morning, only a few months on the job, Carnegie took bold action bordering on the reckless. An accident had log-jammed part of the Western Division. Scott could not be located. Disregarding standing orders, Carnegie, 18, sent instructions under Scott’s name rerouting several trains and quickly unclogged the system. Scott was so pleased that he bragged about it to company president, the formidable J. Edgar Thomson, calling Carnegie “his little white-haired Scottish devil.”

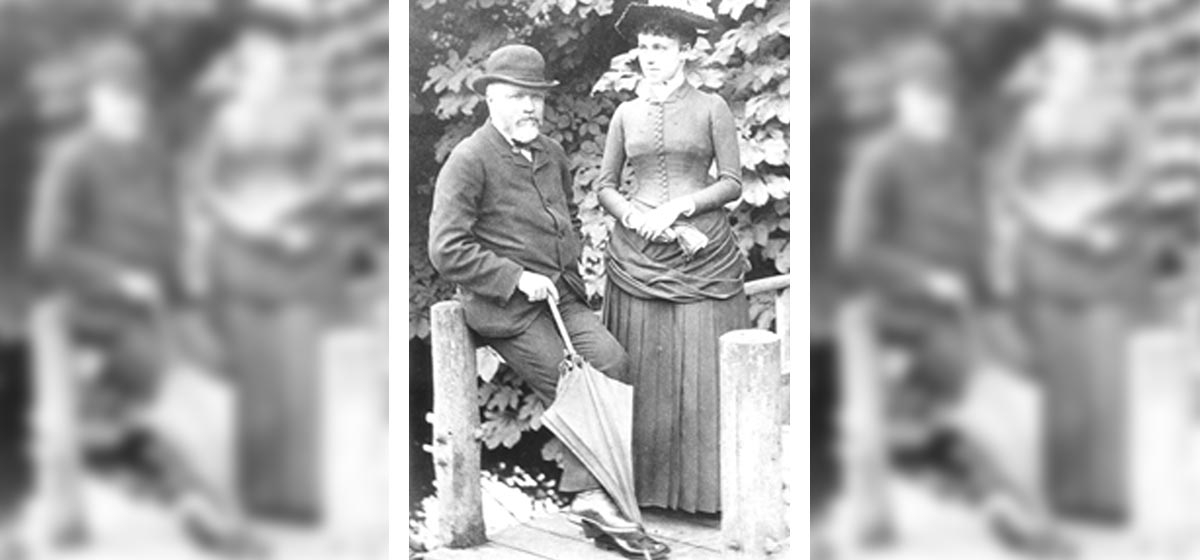

Scott, born in 1820, Carnegie, and Thompson, born in 1808, were linked by a common thread. They had absent or weak fathers, and work became a substitute for family. Thompson was a bachelor, while Scott and Carnegie married late in life. They had father-son roles: Thompson for Scott and Scott for Carnegie; and not the least, each was a born speculator.

As the Pennsylvania Railroad became America’s largest industrial enterprise, “conflict of interest” was almost unknown. It was common for railroads’ key insiders to invest in railroad suppliers and to buy property in the path of new lines — a surefire way to make money. In 1856 Scott arranged for Carnegie to invest $500 in Adams Express, a package shipping company; he loaned him the $500. Similar investments followed. But the bell-ringer was the Woodruff Sleeping Car Co. For an investment of $250 (borrowing the rest), Carnegie held shares that generated $5,000 ($100,000 in today’s dollars) in annual dividends in 1863. Years later Carnegie attempted to rewrite the Woodruff story, claiming that Woodruff, “a farmer-looking kind of man” brought the idea first to Carnegie, who then alerted Scott and Thompson to the opportunity. It was pure fiction.

Set against peers Rockefeller, Mellon and Ford, you had to bet on the spectacularly talented Carnegie. His high intelligence was coupled with gritty pragmatism and street smarts; he was a consummate salesman, using charm and a Scottish brogue which he fell in and out of to suit the occasion. Requiring little sleep, he was a bundle of nervous energy. Today he would be diagnosed as hypo-manic — a variant of manic-depressive conditions with all of the highs and none of the lows. He was also a fearless risk taker. Like all great men, he had a vision —steel — but in this case it came much later. His first 37 years were all about execution.

Deal maker

With the exception of his oil holdings, Carnegie’s investments leveraged his position at the railroad and his relationships with Scott and Thompson. With several successes under his belt, Carnegie pursued an even grander project. The St. Louis bridge vaulted 1,500 feet across the Mississippi with a main span of 515 feet. It was, in the words of the great architect Louis Sullivan, “spectacular and architectonic.”

The high-risk project had state-of-the-art engineering and financing. The St. Louis Bridge Company, Andrew Carnegie principal owner, was the general contractor with Keystone and Union Iron Works (a Carnegie company), supplying the bridge and steel. When Carnegie learned the St. Louis Bridge Company was going to sell bonds to finance the project, he seized the opportunity. He’d succeeded selling bridges, telegraph lines and sleeping cars. Why not sell their bonds? His first stop was Junius Morgan, a rising American banker in London and the father of J. Pierpont Morgan in New York. The 5’3” Scotsman with the sparkling eyes and fast patter soon sold him $1 million in bonds. Getting Morgan gave Carnegie’s substantial reputation a big boost. But then he overreached. He sold bonds for the construction of a railroad from Davenport, Iowa to St. Paul, Minn. In 1873 the project went bad, the bonds went south and this signal failure involved Carnegie in litigation for the next dozen years. J.P. Morgan took notice.

Though an engineering and technological marvel, the St. Louis bridge was behind schedule, over cost and out of money. Carnegie had to turn to J.P. Morgan for interim financing. Morgan didn’t become the premier financier in America without being a superb judge of character. With Carnegie, he was spot on. Morgan could not deny Carnegie’s talents and accomplishments, but Carnegie failed the test of character. He was a fast talker and a sharp dealer – in short, a young man on the make. Morgan set harsh terms. If the bridge was not completed by Dec. 18, 1873, Morgan would foreclose with disastrous consequences for Carnegie. Morgan would have done it in a heartbeat, perhaps with satisfaction. However, on Dec. 18, the span was completed, and Carnegie was saved. More than the sale of Carnegie’s steel interests to Morgan in 1901, the St. Louis project was the pivotal event in Carnegie’s career, a near-death experience that changed his philosophy.

“Master of steel”

Several factors set Carnegie on his course to become the king of steel. First, iron was giving way to steel. Iron was strong but because of its high carbon content, as a residue of the ore smelting process, it was brittle and might fail under sharp stress. Once the carbon was minimized, the resulting steel retained strength but became malleable. The first large-scale device to transform iron into steel was patented in 1855 by Englishman Henry Bessemer. With the Bessemer converter, cold air was injected into the molten iron, reducing the carbon content, thus “converting” iron to steel. During his bond-selling trips to Europe, Carnegie met Bessemer and saw the towering, flaming converters in action. The sight captured his imagination. Iron rails were giving way to steel rails. The latter cost twice as much but gave eight times the life. Railroads at that time were “the” big market for steel. And nobody could sell rails like Carnegie.

So Carnegie determined to concentrate his talents and efforts in one field: steel. In 1872, he proclaimed: “Put all good eggs in one basket and watch the basket.” That year, he put together a steel plant syndicate named Carnegie & McCandless, with his brother Tom and Henry Phipps as partners. The company was capitalized at $700,000 when the average company steel plant was capitalized at $170,000. This signaled Carnegie’s ambition not just to enter the industry but to lead it, all from a start-up plant. His master stroke was hiring Captain Bill Jones who had been passed over for the superintendent’s job at Johnstown’s Cambria Iron Works. Jones had it all. He was mechanically talented and highly innovative with several inventions to his name. He was a brilliant manager and leader who commanded the affection of his workforce.

Profits were at worst adequate and occasionally quite good, but they were sacrificed on the altar of market share. To the consternation of his investors, Carnegie ploughed an excessive 80 percent of earnings into expanded capacity and the most advanced technology. He saw it as the road to dominance and vast profits. The Japanese would succeed with the same strategy a century later.

The renowned Frick

To reduce cost, Carnegie cut wages whenever possible. He also needed low-cost raw material, in particular coke used to smelt iron. In 1881 this brought him face to face with Henry Clay Frick, 14 years Carnegie’s junior, and the “king of coke.” They were an odd couple: the dour and taciturn Frick and the effervescent Carnegie — a listener and a talker. Jones summed it up: “ I don’t particularly like Frick, but you always know where you stand….with Carnegie it’s a different matter. He is a sidestepper.” Frick needed capital. Carnegie needed coke. The initial 1882 investment gave the Carnegie Company 11 percent of H.C. Frick, with Frick as the sole coke supplier to the steel company. This slashed coke costs, and Carnegie was so fond of the arrangement that, unbeknownst to Frick, he and his partners quietly bought shares from Frick’s partners and in three years controlled Frick’s company. This early, contentious tone of the Carnegie-Frick relationship ultimately would yield a bitter harvest.

In 1889 tragedy struck as Jones was killed in an accident at the Edgar Thompson works. For Carnegie, he was the last indispensable man. Scott and Jones were critical to Carnegie’s success. The former plucked him from obscurity and the latter forged the weapon that made him the master of steel. Carnegie shortchanged both. When Scott needed a loan guarantee for his struggling Texas and Pacific Railroad in 1874, Carnegie turned him down. After Jones’ death, Carnegie’s agents convinced his widow to sign over the 50-plus patents Jones had held for a paltry $35,000. Carnegie later admitted that the Jones mixer alone saved the company $200,000 a year over the next decade.

1889 was a pivotal year, and Carnegie made two fateful changes which steered Carnegie Steel for the next decade. Frick became president, with gradually increasing ownership until it equaled Carnegie’s partner Phipps. Years earlier, Jones had hired and mentored an energetic 17-year-old Charlie Schwab. “Smilin’ Charlie” was a complement to the unsmiling Frick. Schwab succeeded Jones at Edgar Thompson and became a confidant of Carnegie, eventually succeeding Frick as president.

The Homestead impact

The facts of the brief but bloody Homestead strike are clear. On July 1, 1892, the Amalgamated Union, along with most of the non-union Homestead workers, occupied the plant. The company advertised for replacement workers in several cities, but before the strikebreakers could arrive, the firm had to regain possession of the plant. To that end, Frick brought in some 300 Pinkertons from Philadelphia and barged them, along with arms and ammunition, up the Monongahela to Homestead.

There was a fatal flaw in the plan, though. The Pinkertons had no direct access to the plant and had to traverse a no-man’s land occupied by a roiling mob of strikers and sympathizers. The Pinkertons were repulsed with an estimated four dead, along with six strikers. This was live “industrial warfare” with gunfire, dynamite, incendiaries and even a small cannon. There were longer and bloodier strikes in American labor history, but none captured the American imagination as Homestead did.

It ended quickly with the arrival of the entire Pennsylvania National Guard, 8,500 strong. The workers vacated the plant and, by the end of July, 500 strikers had crossed the picket line, bolstered by replacement workers.

Carnegie tried to stage manage public opinion from his retreat in Scotland. The original script had him playing the “good cop” to Frick’s “bad cop.” Frick, well cast as the bad guy, had been anti-labor in the violence-ridden coal fields and had maintained that posture as President of Carnegie Steel. A stunning denouement to the strike and to the reputational balance between Frick and Carnegie occurred on July 23. Anarchist Alexander Berkman burst into Frick’s office, shot him twice and knifed him. Frick refused anesthetics so he could guide the surgeon in removing the bullets from his neck and back. He then remained some time at his desk. Frick’s courage did not go unnoticed. While Berkman didn’t kill Frick, he did put a bullet through the Homestead strike.

Carnegie was deep into damage control. His first line of defense was that if he had been there, it wouldn’t have happened. Frick was “young and rash.” Of a long line of Carnegie fabrications, this one stands out: “While in Scotland I received the following cable from the leaders of the union of our workmen: ‘Kind master, tell us what you want us to do, and we shall do it for you.’” Not surprisingly the “kind master” couldn’t produce the cable. Carnegie’s pronouncements compounded matters: “I am a strong believer in the advantages of trade unions …. There is an unwritten law among the best workmen: ‘Thou shall not take another member’s job.’” And to British Prime Minister William Gladstone: “The works was not worth one drop of human blood. I wish they had sunk.” And finally on wages: “We do pay the highest wages in the world …. $2.90 per day ….” The actual figure was less than half.

The public began to see through these deceptions. The St. Louis Post Dispatch wrote: “Ten thousand Carnegie public libraries will not compensate the country for the evils of the Homestead lockout. Say what you will of Frick; he is a brave man. Say what you will of Carnegie; he is a coward.”

The judgment of history fell upon Carnegie not because of his labor practices. Low wages, long working hours and the absence of union representation were generally in line with those of his competitors and common in the industrial landscape. Widespread unionization waited another 45 years until the mid-1930s when John L. Lewis established the CIO. What tainted Carnegie was his public espousal of progressive and enlightened labor policy while practicing the opposite. Piling lie upon lie to salvage his reputation made it even worse.

Cashing out

From 1895-1900, massive consolidation swept steel. The major players were Carnegie Steel (the largest and strongest), Federal Steel (backed by Morgan) and the Moore brothers’ National Steel. Carnegie was mainly in so-called “heavy products:” rails, beams and plates. Its competitors had grown through buying producers of light products, and they began to integrate backwards into Carnegie’s business. It was a serious threat. He had one recourse – integrating forward into light products. Of the move, U.S. Steel chairman Elbert Gary said: “The Carnegie Company would have driven entirely out of business every steel company in the United States.”

When Carnegie Steel approved construction of the world’s largest plant for production of tubular products at Conneaut, Ohio, it was Morgan’s worst nightmare. His vision of the future called for large combines, stable markets and steady profits. Carnegie, in Morgan’s view, was the reigning “prince of chaos” and threatened the industrial system Morgan was painstakingly creating.

Charlie Schwab, now 39, was chairman of Carnegie Steel. His position was far stronger than Frick’s, and he knew how to handle Carnegie: a lot of flattery and a little deception. Morgan called Schwab into a meeting to get his views on the steel industry’s future. Their views were similar. Morgan said he was inclined to buy. Would Carnegie sell? He would. The price was $400 million for the company and $80 million for the estimated 1900 and 1901 profits, bringing the total to $480 million. The estimated profits were inflated by some $30 million. Morgan didn’t care. Better to be cheated by Carnegie than to have him destroy the industry. Carnegie’s share was $225 million ($4.5 billion in today’s dollars). It was the largest liquid fortune in the world.

Redemption

Carnegie would live another 18 years, turning his restless energy to charitable good works. He once said that the man who dies rich dies disgraced. And Carnegie had already established a pattern of charitable giving before selling Carnegie Steel. In 1892 he gave $2 million to build Carnegie Hall in New York. In 1895 he established the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh with $1 million. As the library later expanded into the Carnegie Museums, Carnegie’s total largesse ran to $25 million. He established more than 3,000 libraries throughout the world – costing $60 million. He gave away nearly 8,000 church organs at a cost of over $6 million, a strange gift for the agnostic Carnegie. His rationale: “It lessened the pain of the sermons.”

In 1902 he donated $30 million to establish the Carnegie Institution of Washington as a think-tank for advanced scientific research. About $10 million established the Carnegie Trust for the universities of Scotland. He seeded the Carnegie Technology School, now Carnegie Mellon University, with $7.5 million. Some $15 million created the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, which spawned the giant pension fund TIAA-CREF and the Educational Testing Service. In 1904, he created the Carnegie Hero Fund with $5 million. In 1911, to oversee the many gifts, he endowed the Carnegie Corp of New York with $125 million for “the advancement and diffusion of knowledge.” He gave $1.5 million to build the International Peace Palace for the permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague. In 1910, $10 million established the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Not all his efforts succeeded. He was a fervent anti-imperialist. Upon learning that the U.S. would pay Spain $20 million and then govern the Philippines as a dependency, Carnegie offered President William McKinley $20 million to buy the Philippines and then set them free. He never thought small.

To their credit, most of the creators of America’s fortunes have left a significant portion of their wealth to charity. Nobody, however, did it with the energy and creative capacity of Carnegie. In American history, he was unique. He had the intellectual capacity of a Bill Gates, the vision of a Sam Walton, the gambler’s nerve of a Kirk Kerkorian, the promotional ability of a P. T. Barnum and the philosophical instincts of … an Andrew Carnegie.