An Elegy for Oscar

Some say we love our pets, particularly our dogs, because it pleases and comforts us to do so. I’m not convinced. From my experience with my own dog, who died helplessly of heart failure in his thirteenth year, I felt and still feel a sense of loss that is more than the absence of self-comfort. What I truly feel is what I hope I am able to discover and express in the words that follow. Perhaps our son came closest to my present mood when he said to me on the day after the dog died that suddenly all of Oscar’s toys looked “extra still.”

Oscar was the name our son Sam conferred on him because from a certain angle he resembled a puppet named Oscar the Grouch. He was a Peekapoo and was a gift from Sam to his mother when he was but two days old. At that time he could easily fit into a coffee cup — a wee mouse of a dog. He never grew into a dog of any significant size. At maturity he only weighed between nine and 10 pounds. His major asset was that he never shed — a matter of crucial importance to my wife since she was allergic to the dander that accompanies shedding.

From the beginning Oscar was alert, affectionate and attentive. “I like a dog that makes you think when you look at him,” our son commented at one point, and Oscar qualified. He actually did make you think when you looked at him because you felt he was thinking as well. And his look never wavered. If you engaged in a game of “who will drop his gaze first,” you would certainly lose. Oscar could never be out-stared. Even though, like all dogs, Oscar thought with his nose and talked with his tail, his eyes always seemed to have a mind of their own.

I realize it’s all too easy to become sentimental over a pet, particularly after it is gone and has left its sense of loss in a family, but Oscar was in many ways more than a pet. He was, to put it simply, a presence. You knew he was there not because he called (or rather barked) attention to himself but because he occupied a particular space, modest as it was. And he always seemed happiest when everyone in the family was around him. He simply had to know that we were at home, and that made him a contented dog. When or if we were away — if only for a few hours — he would greet us at the door when we returned with the most welcoming and enthusiastic commotion of which a small dog was capable.

Devotion is possibly the only word that can describe his attitude toward us. It was unwavering. It was the same quality I associated with Argus, the dog of Odysseus, who was separated from his master for two decades — 10 years of the Trojan War and 10 years of roaming the Mediterranean — before his return to Ithaca. When Odysseus set foot on Ithaca after 20 years, Argus instantly remembered him and then promptly died. I think that Homer included this in “The Odyssey” to suggest, a bit too melodramatically perhaps, that Argus managed to postpone death in order to see his master just one more time.

The story is probably apocryphal, but even Homer understood that the devotion of one dog should not go unmentioned. And Lord Byron’s short elegy to his dog Boatswain makes the same point: “Near this spot are deposited the remains of one who possessed beauty without vanity, strength without insolence, courage without ferocity, and all the virtues of man without his vices. This praise, which would be demeaning flattery if inscribed over human ashes, is but a just tribute to the memory of Boatswain, a dog.”

As a further and indelible testament to the devotion of dogs to their masters and vice versa, there is a canine cemetery near Washington, D.C. for those dogs — primarily German police dogs — that were trained for various duties during times of war. These dogs were credited with saving many lives in combat or in combat-related activity. They were assigned to a single soldier-trainer and were faithful and responsive only to him. The result was that they were destroyed when their masters were slain, wounded or discharged from the service. A statue of a single dog oversees the cemetery, and some of the former masters of these remarkable dogs are known to visit the cemetery annually in tribute to their memory.

Oscar was brave but on a miniature scale. His devotion to my wife was such that anyone who was intent on violating her privacy had to deal with him first. And this included me. If my wife were taking a shower, for example, Oscar would station himself and stand guard at the bathroom door. If the door were left slightly ajar and if he heard me approaching, he would slither into the bathroom and, standing on his hind legs, push the door shut with his front legs. He did this to me on more than one occasion. I knew in my heart that if anyone entered the house with the intent to harm my wife, he would have to kill Oscar first.

It made me call to mind two of my favorite quotes regarding dogs. The first is the indisputable observation that dogs through the centuries and in every culture are the “one beast that taketh to man.” Oscar proved that by his behavior every day. And the second is a terse statement made by the poet Mona Van Duyn: “If you want to know what love is, get a dog.” Oscar’s concern for my wife proved that repeatedly.

Over the 13 years of Oscar’s life, I learned more than a few things from him. Trivial as they might seem to others, they came to be invaluable to me. The first derived from the fact that Oscar never became excited unless there was something to get excited about. In short, he did not seek false excitement. If nothing exciting was happening, Oscar was content simply to be a dog. This was never more apparent to me than when he would jump up and lie beside me on the couch when I was reading a book or a newspaper. (In his final year when he could no longer jump up or down, I had to lift and lower him, but the end result was the same.) He would slug himself against my leg and either rest or sleep as if to be assured that I was there and also to assure me that he was where he wanted to be.

Another thing I learned from Oscar was a simple philosophy of pleasure. Oscar had a finite number of earthly pleasures. He enjoyed the very act of eating his meals. He enjoyed drinking water. It reached a point where I took a certain satisfaction in simply watching him eat and drink because he took care to eat and drink neatly and with relish. Another of his pleasures was to find a place on the carpet in the living or dining room where the sun focused itself into a small spotlight. Within that spotlight Oscar would lie in a small coil and sun himself or simply sleep. When I took him outside, he would revisit his favorite trees and do what dogs invariably do against their favorite tree trunks. All of these constituted his few bankable pleasures, and he repeated them in moderation every day and never wore them out.

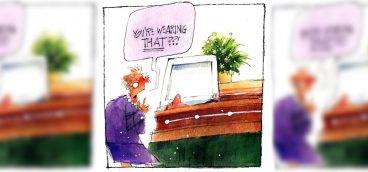

As I said, he had a particular devotion to and affection for my wife. Of course, he would frolic with me or with our son and his wife and their children, but it was my wife who was his anchor. When she had to leave the house for one reason or another, he would announce her return with unstoppable barks of welcome. These would immediately be followed by somewhat angrier barks that seemed to suggest that she had abandoned him for a time for no good reason that was apparent to him. If my wife and I had to go on a trip for a few days or a week, he would greet her with kisses on her nose and cheeks and even on her lips when she lifted and hugged him. And what was most remarkable was that he learned from her to sing — or at least to come as close to singing as a little house dog could come. He sang baritone to her soprano, but he would only sing while he was seated on her lap. And he would not sing for anyone but her. A professional opera singer who was our friend was instantly impressed when my wife and Oscar sang their standard duet for her. She was so overjoyed with the performance that she even tried to have Oscar sing with her. She began to sing a song by Rossini, her particular specialty. Oscar never made a sound. The singer tried again. Oscar remained silent and seemed unimpressed.

Although Oscar was brave when dealing with pain, he had a few pronounced but understandable fears. Thunderstorms terrified him, and he usually hid under a chair or wanted to be close to my wife or myself until they passed. A snap of lightning or a sudden thunderclap would make him shudder almost uncontrollably. He also kept his distance from horses or other dogs, particularly dogs that were larger than he was. On one occasion while we were visiting my brother-in-law, we were unaware that his son had brought his own dog with him. We were also unaware that this dog did not like other dogs and that he outweighed Oscar 10 to one. As soon as we entered the house, the dog pounced on Oscar, leaving him with two deep bite-marks on his right flank. If he had clamped his jaws on Oscar’s head or if my wife had not lifted Oscar by his leash out of the dog’s reach, that would have been the end of Oscar. After the attack, Oscar was subdued, and it was only then that I noticed two bleeding punctures in his pelt. I drove him to a vet’s clinic where he was anaesthetized while the wounds were cleaned and stitched. Later and then for days while the wounds healed, he never so much as whimpered. Nor did I ever hear him whimper except at times in his sleep when he must have been having a bad dream. But then no one is responsible for his or her behavior in dreams, and there is no reason why dogs should be either.

Congenitally, Oscar was a handicapped dog. His father was also his brother, having come from one of his mother’s earlier litters. Consequently the inbreeding left him vulnerable to brief but paralyzing seizures. When they came upon him — and they came unpredictably and without warning — he would contort and go rigid until the seizure passed. At such times all I or anyone could do was stroke him as he lay shuddering and try to soothe him. For a time, we kept him on a regime of phenobarbital, and this seemed to help, but not that much.

On the day that Oscar died, I woke to hear him gasping for breath at the foot of our bed. He was sitting back on his haunches, and his flanks were flexing in and out like bellows. He kept trying to stand, but he could not. I hoped that the spell would pass. As soon as my wife saw that it was worsening, she knew he was beyond our help. I gathered Oscar in my arms and prepared to take him to his regular vet. I placed him on the passenger seat of the car where he kept on trying to stand. Finally, he just turned on his side and lay there gasping. When we finally arrived at the vet’s office, I carried him in, and the doctor saw him immediately. First, he examined his gums and told me that they were quite pale. Then he put a stethoscope to his side. During all this, Oscar continued to try to get to his feet, but his hind legs were no longer reliable. The doctor told me that his lungs were filled with fluid, that this was a typical symptom of congestive heart failure and that the outlook was grim. At that moment Oscar turned on his side as he had done on the car seat and seemed resigned to the inevitable. The doctor told me that it would be best to “put him down.” Facing finality, I agreed but with a slow pain in my chest and throat that made it difficult for me to speak. While he filled his syringe, the doctor asked me if I wanted to stay. I nodded that I did. Less than four seconds later, it was over, but not before Oscar looked at me as if there might be some last thing I could do for him. I returned his look. There was nothing I could do but watch, and we both knew it. The veterinarian felt for a pulse in his neck. “He’s gone,” he said. Then he asked me if I wanted a Kleenex, and I took it.