Editor’s note: Since late 2005, we have interviewed many of the most interesting and noteworthy people in our “city-state of Pittsburgh” as my old editor and friend John Craig used to call this area. The number of interviews that have appeared in this magazine reaches well into the hundreds (writer Jeff Sewald alone has interviewed nearly 80). As a special 20th anniversary issue treat and a tribute to the greatness of the light and lives that course through Pittsburgh, we’ve put together a compendium of thoughts from a fraction of these interviews. We’re sorry we can’t include all — space simply won’t allow it. But I hope you enjoy reading the wit and wisdom of these Pittsburghers, many no longer with us, as much as I enjoyed editing them.

– Douglas Heuck

Previously in this series: 20 Years of Interviews Pt. I

Paul O’Neill

Alcoa CEO and U.S. Treasury Secretary

“Borrowing from 15 years of government service and more than 20 years in the private sector, I was trying to think: What are the common elements of what I would consider to be success? Where you find real success, first of all, you find a vision of excellence. It’s not just one person’s vision of excellence but one that is shared in the community. The second characteristic of success is not being denied execution. It’s a determination to knock down walls or whatever it takes to succeed. And the third element is speed of execution. You don’t sit around and wait and hope and wish. You actually go commit things and do things.”

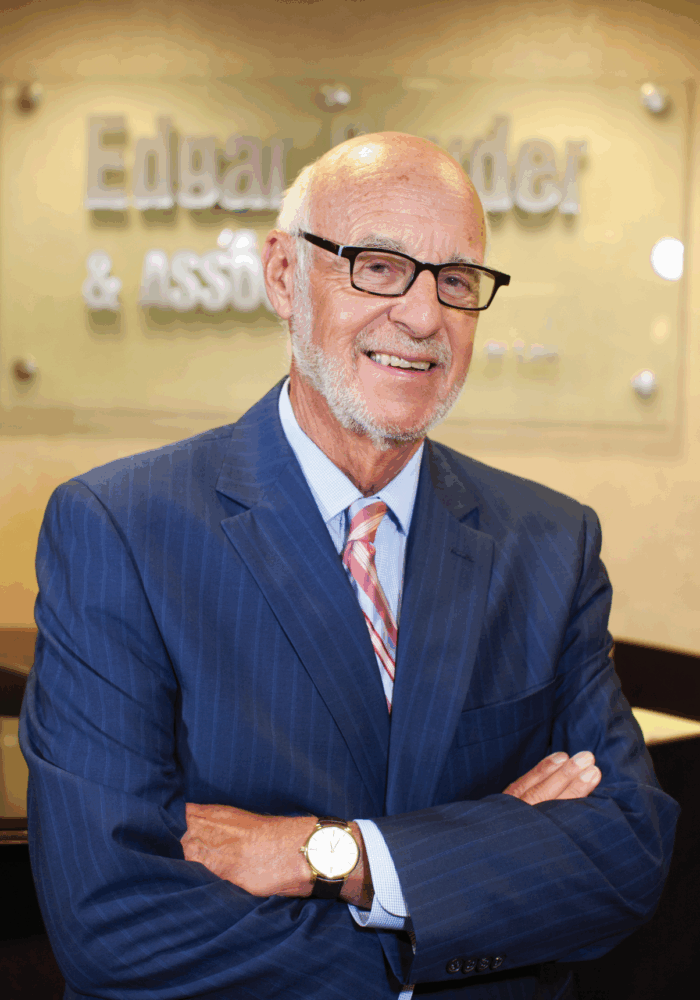

Edgar Snyder

Attorney

“My brother, the physician, was truly the pride of our family. And I was determined to make my parents proud, too. Unfortunately, when I went to Penn State and got a ‘C’ in chemistry, my hopes for a medical career were dashed. But I remember, at the time, having a conversation with my mother, who was a very funny person with a great sense of humor. She said to me, ‘Edgar, if you can’t become a doctor, you should become a lawyer because you’ve got the biggest mouth of anybody I’ve ever met.’ She was right. I could argue about anything. At Penn State, I put my big mouth to work as a member of the debate team. I was captain for two years, competed in different parts of the country and, as a result, was able to hone my ability to speak and to think quickly. My strong suit has always been the ability to articulate concepts and ideas, not my intellect. Given my big mouth and ability to articulate, law school did indeed seem right for me. So, I went to Pitt for law school and was truly lucky to survive, graduating near the bottom of my class. That’s the truth, and I don’t try to hide it. It serves many people well to understand that you don’t have to be a top student to become something in life. It’s what you choose to do and how hard you’re willing to work at it that counts.”

Manfred Honeck

Music Director, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

“Every human being develops in his or her own way. I’m sure that I am a little different from my parents, and also from my brothers and sisters. But because of my faith, I began to understand early that it would just not be possible for me to live in this world happily without thinking of others. One can decide to be an egoist or one can decide to encounter the world with open eyes. If you do the latter, you will see the wonderful creation around you. You will also see the challenges you will likely have to face in time. We all go through good times and not-so-good times. That is life, for everyone. We must embrace it all.”

Dr. Cyril Wecht

Forensic Pathologist

“I’ve probably done more exhumations than any other forensic scientist in the country because my work has been so involved in medical-legal matters. In fact, I just did an exhumation for a guy who’d been dead for two or three years. And even I, after 45 years and more than 100 exhumation autopsies, for a moment thought, ‘What the hell is this?’ My nose is yours and my eyes are yours. I can smell and see what you smell and see. But there are certain things to which you can’t acclimatize. For me, the most important thing is never to lose cognizance of the fact that I’m dealing with deceased human beings. Somebody somewhere loved these people. These situations must always be handled with great dignity and respect.

“Sometimes comments come back, often snide, about my involvement in certain high-profile cases. Well, that’s what I do as a forensic pathologist. My work with the media hasn’t kept me from doing autopsies. Does it make me an egomaniac to say that I enjoy the media and being on TV programs? I don’t think so. I don’t rush home to see myself. The producers send me discs of the shows and I don’t look at them. I simply don’t have the time, and I watch very little TV anyway. I read five newspapers every day—four on Saturday when there’s no USA Today, and three on Sunday. (There’s no Wall Street Journal on that day, either.) I still work seven days a week, many evenings, and I like to write. I don’t waste time. I give interviews, even while I’m in the car, via cell phone. I get many requests from students and I’ll often have them call me at home on weekends when I’ll have more time to spend with them. Sure, I work hard. And yes, I’m proud of what I do.”

Kathy Humphrey

College President

“In kindergarten, I struggled at the white school because the other children wouldn’t play with me. I was different. I was strange to them, and I didn’t come to school the same way they did. And I didn’t live in their neighborhoods. I complained to my parents about this, and I remember hearing them talk about whether they should move me back to the neighborhood school. They decided not to do that because they believed it was important for me to learn to survive in that world, and I’m grateful today that they didn’t make me change schools. The experience taught me how to live in two different worlds, and to communicate in two different ways, so much so that my father used to say to me, ‘You’re going to make it, Kathy, because you understand how to communicate with white people.’

“My parents were very forward thinking, and education was crucial to them. They were willing to make great sacrifices for it, and it made me grow up fast. I was independent in many ways and comfortable in different situations. In school, I sought out many student leadership positions. A person had to be fearless to do that, and a lot of my fearlessness came from my mother and father. They were always clear because when you have as many children as they did, you have to be regimented and organized to function. Still, I used to say to my mother, ‘When I grow up, nobody’s going to tell me what to do,’ to which she replied, ‘Kathy, somebody is going to tell you what to do for the rest of your life. If nothing else, you’re going to have to obey the stop signs.’ ”

Richard V. Piacentini

Botanist and Innovator

“I had polio as a kid and because of that I was not really good at the kinds of sports that one normally would play in high school. That, combined with the fact that I was shy, meant that I wasn’t very popular. But when I was around 12 or 13, my parents signed me up for sailing lessons and I really excelled at it. I was the skipper and my brother Kevin was the crew. One summer back on Long Island, there were 14 local regattas and my brother and I won 12 of them. (In the two we ‘lost,’ we actually tied for first.) That year, the nationals and the North American championships were set to take place in Massachusetts. We thought about entering, for about a minute or two, but then decided to forget it. It was inconceivable to us that we could win anything like that, so we decided not to go. But two guys — whom we consistently beat all summer long — did enter and came in first and second in the nationals and third and fourth in the North Americans. To this day, I wonder, ‘If we had gone, would we have won? If so, how different might our lives be today?’ Of course, we’ll never know. But that experience stuck with me. That’s why I decided I had to go for the career I wanted. I didn’t want to be asking myself forever, ‘What if?’