Q. You’ve been a leader in the Pittsburgh community for decades, serving as president of the Mt. Lebanon School Board, managing partner of Pittsburgh’s oldest and most prestigious law firm — Reed Smith, president of the Allegheny County Bar Association and the Academy of Trial Lawyers, board member of several nonprofits and through your private practice as a litigator and mediator. How would you describe your upbringing and education? Why did you become a lawyer, and were there any key lessons or teachers that formed your approach?

A. I was born and raised in Mt. Lebanon in a “Father Knows Best”-type environment. My parents were active in the community — on cultural and nonprofit boards and in politics. My father owned a manufacturer’s agency, selling parts to the steel industry. I just coasted through high school with no particular vision of what I wanted to do. My guidance counselor kept talking about Kenyon College, which had something called the “Kenyon Plan” — a system that basically recognized Advanced Placement courses. She figured I wouldn’t get in, but when I did, I felt that I had no choice but to attend. I was an econ major there. My father wasn’t a big liberal arts fan, so economics was the closest thing to his preference — a business degree.

I also coasted through college, still with little sense of direction, so I decided to go to law school to keep my options open. I could teach or go into business or practice law. The idea behind going to Pitt Law School was that, if I was going to practice in Pittsburgh, it would be good to have established friends and contacts from school. The whole approach of keeping my options open, however, was derailed by the Vietnam War, which wiped out graduate deferments overnight. It was a rude awakening; all of a sudden the war we were watching on TV was very much a reality. There was no doubt I was going to be drafted, and I wasn’t excited about my options, so I decided to enlist in the Navy, jokingly because they had the best-looking uniforms and because North Vietnam had neither a navy nor an air force.

When I went for an interview, there were hundreds of guys in line. We waited all day for a single interview when the recruiting officer told me that there were only four billets (openings) in Pennsylvania for a Navy commission, “so don’t hold your breath.” Afterwards I was sitting in my apartment thinking, “What a waste of my day” because I figured that I wasn’t going to be able to finish my second year of law school. A friend called and said, “There’s a bar on Route 51 that’s giving away its whole stock of liquor. Let’s go for free drinks.” When I said I hadn’t done my reading for class, he said, “What are you, crazy? We’re probably going to be dead in Vietnam next year anyway.”

After waiting in line to get into the bar, we had to push our way through the crowd and wave a $20 bill for the bartender to serve our “free” drinks. I turned to my right and who was standing there, but the recruiting officer in his whites. I never moved that whole night. If I had had to go to the bathroom, I would have gone in my pants. I stuck to him, “bought” him drinks (bribed the bartenders) and by the end of the night, we had become best friends. I figure that’s how I got my commission.

Stroyd is a winner of Kenyon College’s Gregg Cup, which has been given for the past 90 years to the alumnus “who has done most for Kenyon during the current year.”

At the time, I wasn’t excited about it because I had to leave law school after my second year, but looking back, it was a life-changing step for me. Military service is as close to a meritocracy as I’ve ever experienced. You’re rewarded in direct proportion to your efforts and your results. It was about how far you were willing to go beyond what’s expected of you. Having spent my life coasting, I realized that the more I invested and went beyond what was expected, the greater my reward — a lesson that I carry forth today.

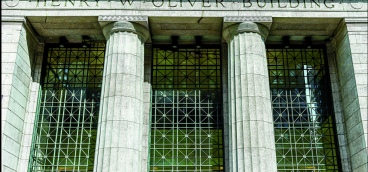

It was life-changing for a second reason. When I was discharged and had finished law school, I didn’t know where I wanted to practice law, so I applied to be a law clerk with a number of judges, including Judge Joseph Weis, a decorated World War II veteran. The Federal Courthouse is now named for him. He would get a couple hundred resumes every year, and I suspect that mine went to the top of the pile because of my military service. I know he always valued the discipline, focus and personal sacrifices that people in the military made. My career path as a lawyer would have been different had I not clerked for him. He wasn’t just a role model; he was my mentor. He was in his 40s when I clerked for him and was 91 when he died, so he was my mentor for 40 years. I never went to the courthouse without visiting him. He guided me though my career and what was going on in my life.

As my role model, Judge Weis embodied every trait that most people imagine a judge and lawyer should have. He was beyond reproach, principled, calm, well prepared in every way, generous with his time, sincere, polite, good humored, respectful and empathetic. He shared his impressions about who were the most effective lawyers and why with us law clerks. He explained why some lawyers were viewed as credible and trustworthy and why they were considered dependable and believable. It was a graduate course in law and psychology — chock-full of lessons that a young lawyer needs. Judge Weis always took the high road and frowned on guerrilla tactics of intimidation. He was the reason for my staying in Pittsburgh.

He introduced me to Walter McGough, head of Reed Smith’s litigation group, and counseled me to work there. “Walter’s going to teach you how to be a good trial lawyer.” And he was right. It was a fantastic experience, and in addition to teaching me how to try a case, he exemplified the best in terms of excellence, preparedness and commitment to his clients and to serving the profession.

Frankly, that kind of experience doesn’t happen much anymore. One of the big draws to practicing in Pittsburgh then was how the lawyers here treated each other with respect; they were effective advocates for their clients but at the same time were civil with each other. Compared with Philadelphia’s dog-eat-dog legal community, Pittsburgh was an ideal place to practice because the other lawyers made my job enjoyable. To this day I love going to the office every day.

The practice of law today, however, is a little different. First, there are lot more lawyers than back then. If you were obnoxious, used intimidation, tried dirty tricks and couldn’t be trusted, word got out and you would be shunned in the legal community. Back then, you’d have one case against a lawyer this year and may be two the next, so everyone had to be courteous and accommodating because you would be dealing with that same lawyer again and again. Now, it’s unusual to have another case against the same lawyer within a couple years.

Q. You do something that, at least to my mind, is unusual in a legal case. Is it true that you try to meet privately with the opposing attorney early in a case to develop a rapport and understanding with him or her? If that’s true, why do you do it?

A. Lawyers should be working toward a solution, rather than needlessly fighting over every little detail, many of which are meaningless in resolving a case. That’s the reason why I prefer to sit down with the other lawyer at the outset of a case so that we can have a civil relationship, rather than be suspicious and less than forthright with each other. If you believe that the other person’s going to stab you in the back every time you turn around rather than being professional, the relationship is going to be unpleasant for the lawyers and, ultimately, not good for the clients. With civility and professionalism, an advocate’s days are more productive and enjoyable. Instead of fighting with an enemy, you’re dealing with a colleague, and you’re both working toward a solution. Are we in World War Three or are we trying to resolve a dispute? Remember that 90 percent of the civil cases settle.

I recognize, however, that a lot of people don’t want to find a solution. They want to be vindicated. Maybe those are the 10 percent that go to trial. Most litigants, however, eventually realize that a lawsuit is so distracting and so expensive that they need it to be over. I try to explain that at the beginning of a case to my clients. A lot of times, though, they don’t want to hear it, and I say, “Okay. I understand that you want to go ahead, but remember this conversation. Eventually we’re going to be looking for a compromise to put it behind us.”

There are some clients where my philosophy and theirs are never going to mesh. In those cases, I say, “Maybe there are other lawyers who’ll do a better job for you.” It doesn’t happen often because they usually don’t call me in the first place. To the extent that I don’t say no to them, I inevitably regret it because they’re never going to be satisfied, and I’m frustrated trying to please them when prosecuting their case.

Q. You’ve been a sought-after mediator for a long time. How did you get into that? Is it something that happens because, in an adversarial profession, people trust you to come to a fair conclusion?

A. Mediation does draw on my experience representing and dealing with frustrated litigants — either my clients or the other side — and trying to find a way to a middle ground. It does take a little experience to pull that off. I started mediating cases more than 30 years ago.

Art Schwab, an innovative federal judge in Pittsburgh, launched a pilot program for mandatory mediation. He and I knew each other from clerking on the Third Circuit, and we shared a suite at Reed Smith, where Walter McGough would tell his secretary to get one of “The Performing Arts” whenever he couldn’t remember which of us was working on a case with him. Art thought I’d be a good person to be one of the early mediators, so I went through training and have mediated more than 100 cases since then.

Maybe a third of my practice is mediation, but I don’t do any advertising. Although there’s no pressure on a mediator, in terms of winning and losing, it’s exhausting, analyzing both sides’ positions, probing their needs and trying to work with them to come up with mutually acceptable solution. More and more lawyers are putting out their shingles as mediators, figuring that it is a pressure-free aspect of practicing law but not realizing how draining it can be. Some are good but not as many as there should be, in that most civil cases settle.

An effective mediator needs to have credibility with both sides, needs to understand the law and needs to appreciate the stresses that the litigants and their lawyers are under. Mediation requires as much diplomacy and creativity as patience and ability to listen.

At the outset of a session, I tell the lawyers and their clients, “If we’re able to find a middle ground — a compromise — one side’s going to take a little less than you wanted when you walked in the door and the other side is going to dig a little deeper than you wanted.” I tell them that my goal is for them to walk away dissatisfied — but equally dissatisfied, because that’s what a fair and equitable compromise means. Neither side should be giving “high fives” but both sides will be able to put the dispute behind them and move on with their lives. So that’s my goal — to make everyone somewhat unhappy but equally unhappy, and sometimes, I succeed even if there’s no settlement!

Q. That is clearly a skill or wisdom that is increasingly lacking in our world. What are the keys to it? Have you gotten better at it in time? And what has it taught you about people and human nature?

A. If making concessions is the key to a successful mediation, I would starve if I were a mediator in Washington, D.C. working to resolve their disputes. Of course, I understand why the politicians don’t want to compromise. Their political bases would vote them out of office if they concede anything.

I’m a lot more patient with the negotiating process now. Basically, I find out what the parties really need — as opposed to what they would like to have. If we can sort out those differences and focus on what they need to have, then we might be able to arrive at a middle ground.

People usually start out demanding what they hope to get, and I let them air that, but before they get their heels dug in, I try to convince them it’s not going to happen — not by telling them outright but by leading them to that conclusion. I reason with them and point out where their positions may not be as strong as they think. I help them have a more realistic assessment of what they need and are likely to get. My job is not to judge — it’s to help them make a realistic assessment of both sides of the dispute.

Most of the time, we find a compromise. The federal system requires mediation within the first 60 days, which can sometimes be too soon. Emotions may still be too high or facts still too sparse.

Trust is half the battle in working toward a settlement. They’re trusting me to assess their case, and they’re trusting me to evaluate the other side’s case. You don’t get that as easily on Zoom. With the pandemic, we had no in-person mediations. Unless I knew the lawyers well, I was just a face on the screen and didn’t have much credibility. It was also harder for me to assess the nuances of a case and the people, so the Zoom world did not result in as many cases settling.

I generally prefer face-to-face sessions, but a lot of clients are from out of town and don’t want to pay to come here or to have me go there.

Q. As you look back over your career and into the future, what concerns you and what encourages you?

A. Diminished civility and professionalism in the legal community concerns me — and perhaps that’s a problem today with people in general. Clearly, there’s less tolerance and less willingness to accept other people’s viewpoints. There are many extraordinary pressures on people today, and a lot more seems to be riding on issues and disputes on a day-to-day basis.

Also, there was a time when there was more loyalty between clients and their lawyers. One of the things I regret about the legal world is that, to a degree, it’s become “What have you done for me lately? I want your best work product in the shortest amount of time at the cheapest price.” Some clients treat their relationship with their lawyer like a commodity, not as an on-going partnership of trust.

When I recently accepted an award from Leadership Pittsburgh, I emphasized the idea of opening our eyes and minds to issues and people with whom you might not otherwise agree. I don’t think we listen to each other as much as we used to. My sense is that politics and our city have become more insular. A “cancel culture” is all too prevalent now. If there’s a single issue you disagree with, you write off that candidate and that political party entirely. We need to appreciate our common grounds, even if we may disagree on particular points.

I have always been blessed with exceptional role models — at Reed Smith, Judge Weis, and my parents — people who steered me in the right direction and helped me along the way. One of the things that was rewarding when I was delivering my remarks at the Leadership Pittsburgh awards luncheon was how many people in that room were there because of their commitment to community service and because I had been able to help them along the way. It was an emotional moment for me — to consider that maybe I’d followed the examples that had been set for me and had helped people in their careers and in their lives.