Clan Carnegie

The fact that the Carnegie Museum complex in Oakland happens to be located on Forbes Avenue wouldn’t be particularly noteworthy except that Andrew Carnegie and Brigadier General John Forbes both hail from the small town of Dunfermline, Scotland.

Forbes named our city, Carnegie put it on the map, and both longed to return to Scotland. Forbes never made it, dying in Philadelphia, where he is buried. But Carnegie did go home again and again, leaving a strong philanthropic legacy. Pittsburgh and Dunfermline have another commonality. Dunfermline is the site of the first Carnegie Library in the United Kingdom, while the first in the United States was built in Pittsburgh.

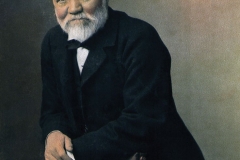

Just a short train ride from Edinburgh, Dunfermline is home to the Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum and John Forbes’s Pittencrieff estate, now a park. Young Carnegie and his family lived in a one-room cottage and were restricted from going onto the grounds of Pittencrieff. “But as a boy Carnegie was very aware of the exploits of General Forbes,” said Angus Hogg, trustee of the Carnegie Dunfermline and Hero Fund trusts. General Forbes, born more than 100 years before Carnegie, was a heroic figure to the young man.

Before the Carnegies left for the U.S., little Neg or Negie, as Andrew was called, enjoyed stories about William Wallace, Robert the Bruce and other heroes of Scottish history. “He was very close to his mother as well, and most like her in character,” said Lorna Owers, manager of the Birthplace Museum. “His younger brother, Thomas, was more like the father.”

Carnegie’s father, William, was a hand-loom weaver, and when the bottom fell out of that industry, in 1848 he moved the family to Allegheny City. “They sold absolutely everything to get there, but the father never did manage to make a living and died in Pittsburgh in 1855,” said Nora Rundell, CEO of the Carnegie Dunfermline and Hero Fund trusts. It was young Carnegie who supported the family, going to work as a bobbin boy at 12.

After he made his fortune in steel, Carnegie went back to Scotland and bought the Pittencrieff estate, donating it to the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust for the benefit of the community. “He had the last laugh on those who wanted to exclude him,” Owers said.

She explained that Carnegie’s family subscribed to the working-class Chartist movement for political reform and did not believe in inherited wealth and position, which the monarchy represented. It was part of what fueled his desire for philanthropy. However, contrary to what some believe, he did leave his family comfortably well-off, even while giving the bulk of his fortune—some $350 million—away. In 1901 he sold Carnegie Steel to J.P. Morgan for $480 million; Morgan created United States Steel after the purchase.

“Many believe it was Carnegie’s wife, Louise, who really encouraged his great philanthropy later in life,” Rundell said. Carnegie and Louise had one child, Margaret Carnegie. She married Roswell Miller, and they had four children before they divorced. Louise, the oldest child, married James Gordon Thomson. They had five children before she died at 27 of polio. The Thomson children—Mary, Louise, Betty, Margaret and William—were all born and raised in Scotland.

“I am sure my great-grandfather would have been enormously proud of the achievements of his foundations around the world,” said William Thomson, former president of the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust and now its honorary chair.

Thomson and his siblings grew up in Edinburgh and Skibo Castle. Looking over the Firth of Dornoch, Skibo is the Highlands estate Carnegie bought for his pregnant wife. It provided an idyllic escape for the young Thomson children. “It was our second home, really, because my father lived in Edinburgh, and we would spend summers and holidays there, except for Christmas, because it was closed up in the winter.”

Margaret Carnegie Miller, grandmother to the Thomson children, spent the winters in the U.S., where she died in 1990 at the age of 93. Thomson and his siblings would go to Skibo for Easter, and their grandmother would arrive in May and stay until the fall.

“My grandmother was very kind to us because when my mum died, my dad was faced with what to do with us, really,” recalled Thomson’s sister, Margaret. “Back then I lived in this sort of dream world and never thought of Skibo coming to an end.”

Their grandmother insisted they spend as much time as possible at the estate, which included what was considered a model farm and dairy. “I remember cleaning udders and milking my cow,” said Margaret, who developed a love of animals and country life from the experience. “I decided when I was 15 that I always wanted to live here. I carved my initials in a tree under a flap of bark, ‘M.T.’, and made a vow that this is where I wanted to spend the rest of my life.” Today Margaret lives with her sister Mary, neither of whom married, on a sheep and cattle farm five minutes down the road from Skibo.

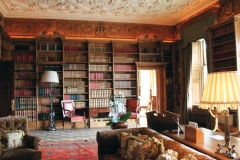

“There is a lot to see at Skibo,” said William Thomson, who as a child kept hamsters in what was Carnegie’s bathroom. “The pool, which has been restored, was really quite something in the 1900s. When my great-grandfather bought Skibo, he set about making many improvements. He brought architects in and expanded it enormously. Only a small part in the front is original and even that had been restored.”

In 1982, Carnegie’s daughter left Skibo, and it was sold to become what it is today, the exclusive Carnegie Club, with a membership fee of £20,000 (nearly $32,000) and annual dues of £7,660. Just outside the town of Dornoch, it is probably best known for hosting the wedding reception of Madonna and Guy Ritchie. Asked during a recent dinner at Skibo if she was sad to see the estate sold, Margaret Thomson said she wasn’t. “We couldn’t afford to keep it. It’s so huge, and once your family leaves, it’s no longer the same place.”

At dinner, Margaret wore the same red Carnegie tartan her grandmother favored, and around her neck she wore her great-grandmother’s watch on a chain. Margaret seems to have inherited the same twinkle in her eye that her great-grandfather was said to have, though what she knew of him as a young girl was limited. Her grandmother didn’t talk much about her parents.

“They were a very loving trio, and she was very private when it came to that,” Margaret said. “Carnegie was such a personage in that day, and this was a young girl growing up in that atmosphere. She was proud of him, there is no question about that, but she learned not to talk about him. She was also a little bit afraid of him, because he was so much older, she told me, but she adored him.” She also recalled her grandmother getting “a wee bit uptight” when people started talking about him. “I think she felt he was often misquoted.”

Margaret remembered, as a child, going into a shop in Edinburgh. “I was with my sister, and I heard this kid wanting this toy or something and the reply was, ‘Who do you think I am? Andrew Carnegie?’ ”

She and her siblings grew up being shy about being Carnegies. Margaret knew her great-grandfather was a philanthropist and gave away organs and built libraries. “I have to say, very much to my shame, I didn’t know much more about him.”

It was when Margaret visited Pittsburgh earlier this year for the 100th anniversary of Carnegie Mellon University that she learned more about what her great-grandfather had accomplished. “I realized Grampa Negie was kind of fascinating when we visited the Hall of Architecture at the Carnegie Museum. All these plaster casts of the wonders of the world he had made for the masses, for the people who could never see these things. He didn’t purloin them, which I think was good, and, maybe because he was Scottish, he didn’t want to pay for them. I don’t know,” she said laughing.

It was also during that visit that she realized how much his philanthropy continues to mean to others. “Students would come up to my brother-in-law and me when we were walking across the campus and thank us for what my great-grandfather had done.”

What she most admired about Carnegie was the way he got people to invest in their future. “What I think was brilliant was that you could ask him to build a library or a university and he would say, ‘OK, you buy the land or you get the books.’ The minute you have input yourself, you look after it. There is an incentive, and I think he knew that. Scotland will give you everything. Don’t you think that’s where we went wrong?”

A symbol of what has gone right in Scotland are the Carnegie Trusts. They are headquartered in Dunfermline under one roof in the Carnegie House, which opened in 2008. It’s home to the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust, The Carnegie Hero Fund, The Carnegie UK Trust and the Carnegie Universities of Scotland Trust.

“It was William Thomson who masterminded war and peace between the different factions of who would get what in the new space,” said Hogg. “And in his usual diplomatic fashion, he steered us through the process of co-location.”

“The architect was amazed that this could work, but in fact the trusts had a common purpose, so it wasn’t that difficult,” added Thomson.

On the walls are several Italian watercolors from Skibo that Carnegie purchased during his travels abroad. Thomson added that “he was quite well conned, particularly with Scottish things. There is a glass cabinet in the drawing room at Skibo, and among other things, a cup and a saucer that had been used by Bonnie Prince Charlie, allegedly. They were like relics in a Catholic Church; somebody’s lock of hair but most of them were absolute nonsense.”

Margaret recalled another of Carnegie’s passions, one that some believe killed him. He died in 1919 and is buried in Sleepy Hollow, N.Y.

“Grampa Negie was a pacifist, maybe because of the Civil War. He went over to Berlin to see the Kaiser to talk with him and stop him from going to war. This was 1913, I believe. He came back believing he had been successful. When war was declared, according to the family, it broke his heart.”