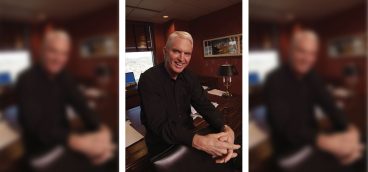

What Do I Know? Guillermo Velazquez

My story begins in Mexico City.

I am the youngest of eight children, and my father passed away from liver disease when I was 11. When someone in your life dies while you are still young, you don’t really understand what’s happening. All I knew was that I saw my father working, and then he was gone.

I did well in school and my mom was very proud of me. But when you do well, there is always pressure to do well the next year, and every year after that; it’s expected. I always had good grades in school, and that got me recognized, but my mom couldn’t be present when I received rewards. She had to work.

At 14, I was enrolled in an entrepreneurial program that teaches kids how to build and run a company. I did this while still in high school, and when I graduated at 18, I left with a degree in business. For me, it was exciting because I was always very clear about what I wanted to do and what I wanted to be. I wanted to do business, and I wanted to travel the world and speak many languages. That was my dream.

My mom wanted me to become a lawyer because all of my uncles from my mom’s side were lawyers, as were her cousins, and I almost went that way. But I never felt like I wanted to be a lawyer. Some of my high school friends ended up in medical school, and I almost went that way, too, because, at that age, I was simply trying to figure things out. But I didn’t see myself as a doctor, either.

The entrepreneurial program took place alongside my traditional schooling. You could spend as little as one year in the program, but I stayed for 10, even through college, because it was so much fun for me. I made a lot of friends, but I can say that I was one of the few students there who had a clear goal in life.

The Pittsburgh Hispanic Development Corporation’s Business Incubator guides entrepreneurs to assess their business ideas, and to plan, launch and operate their businesses.

One thing that I liked particularly was that the entrepreneurial program had a cultural-exchange aspect. If you wanted, you could host a student from a different country in your home. Or you could apply to go to another country and be hosted there, mostly to learn about a foreign culture, to try out a new language, and to see how people lived. But if you wanted to go to the U.S. or Canada, you had to be bilingual and, at 20, I did not speak English at all. So, I told my mom that I wanted to learn English and that I had to attend a specific school to do it. She didn’t really want this so, essentially, I had to pressure her to pay. With some money she had saved from my dad’s pension, my mom finally allowed me to go and learn English and, by 22, I was bilingual and earned a diploma in English as a second language (ESL).

Having learned English, I decided to enroll in the exchange program and was selected to go to the U.S. But we were so poor that we didn’t have the money to pay for the airfare, which was required. As you might imagine, I was very disappointed, yet I remained in the entrepreneurial program. I wanted to keep learning and, at that point, to begin working. I didn’t want to finish school, with a degree, and start from zero. So, I told my mom, “I’m going to go to work,” and she didn’t want that either, because none of my brothers or sisters worked before graduating. But I assured her that I could handle it. So, I began looking for a job, and then, boom! I got hired by Nissan Motor Corporation, mainly because I was bilingual, and completed my last year of college.

At the time, one of my classmates in Mexico was hosting a foreign exchange student from Pittsburgh. She didn’t speak Spanish, so I became her personal translator. I loved it because it allowed me to practice English, and we became friends. It was she who convinced me to apply again for an exchange. “Where could I go?” I asked. She said, “Why not go to Pittsburgh?” And I said, “OK, I’ll apply.” Boom, again. I was selected and, in January 1996, I arrived in Pittsburgh.

At first, I was staying in Springdale with my host family, but they decided to sell their house and I moved to New Kensington. I was doing an internship at The World Trade Center in Pittsburgh, so I had to take the bus all the way from New Kensington to Downtown every day. About a month after I started that internship, I learned that they wanted me to stay on and work full time, but that wasn’t my plan. Sure, the job would afford me an opportunity to practice English all day; on the other hand, I told myself that I had promised my mom to return to Mexico. So, I made a request to them: “Can I tell you in two weeks?”

Latino business is the fastest growing segment of the U.S. small business

ecosystem.

For the first week, my mom cried day and night and I thought, “I’m not going to be able to do this.” By the end of the second week, I had made up my mind. I was going back to Mexico. I couldn’t bear my mom’s tears any longer. When she finally called me, she had calmed down. “So, what’s going on with that job offer?” she asked. “Is it still on?” I said, “Yes,” to which she replied, “You should take it.” “Are you sure?” I asked. She said, “Yes.” A year later, when I went home for a visit, I learned that my brothers and sisters worked hard to convince my mom to let me stay here. But I still didn’t think I was going to stay in Pittsburgh long term. It’s not that I didn’t want to be here; it just was never my goal to stay. Pittsburgh was very far away and, culturally, couldn’t have been more different. Nobody here spoke Spanish. I had no friends. And when everyone left work at 5 o’clock, I would stay because, what else would I do? I couldn’t go back to New Kensington and do nothing. I didn’t even have a TV!

In the evenings, I worked late at The World Trade Center, helping one of our clients to expand internationally. In time, that company hired me and I worked there for almost 15 years. I was always on the go, constantly shuttling between Latin America, Europe, and Canada. It was fine because I was still in my 30s, which is a good time to do that kind of thing because you have the energy. But even back then, I always wondered, “How and why did I end up in Pittsburgh, of all places?” I wanted to move to Washington, D.C., and I applied for jobs in California, so I tried my very best to leave. I even built a house in Mexico because I thought I was going to go back there. But somehow, I just couldn’t move away.

Soon after 9/11, I qualified for U.S. citizenship, but was not sure that I was going to apply because I was still thinking about heading home. Traveling at that time was a nightmare and, eventually, I got tired of it. Then one summer, I returned from a trip overseas. I landed in Pittsburgh on a Sunday afternoon, and the weather was very nice. I said to myself, “Ahh, I’m home.” And that’s when it hit me. Pittsburgh was really my home now. So, I decided to become a U.S. citizen.

Pittsburgh is a good place to live. But in time, I began to do some soul-searching. I have always been the kind of person who wanted to do something to help people. As a kid, my family lived close to a convent, and my mom would send us kids there to help the nuns with their planting, to water their gardens, and so on. During vacations, I had to go to the convent every day. I believe that the nuns transferred good values to me, and I carried them with me to Pittsburgh, wanting to do something good.

One day, I ran into Victor Diaz, founder of the Pittsburgh Hispanic Development Corporation (PHDC). I had known Victor since 2000, when I was still at The World Trade Center. In passing, I said to him, “I’ve always wanted to have a master’s degree, but I will never be able to do it given the full-time job I have now.” He replied, “Why don’t you come and work for us? We have a part-time job for you. We just received a grant for this new organization we created.” It was the answer to my prayers.

When I joined the PHDC, all it had was a mission statement. I jumped in because Victor told me they wanted to create an incubator for Latino businesses. “An incubator?” I thought. “I know how to do that.” Then he added, “We also want to have a housing program.” I thought again. “I don’t know exactly how to do that, but I’ll figure it out. Can I start with the incubator?”

Next, I asked Victor, “Where’s the business plan?” “There isn’t one,” he said. “You’ll have to create it.” So, off I went to develop the PHDC’s programs: the business incubator; a housing component; and, then, later on, an employment initiative and an ESL program, all the while working on my master’s degree — an MBA in global management — at Point Park University.

Early on in my tenure at the PHDC, we were having conversations with the City of Pittsburgh about the space in which we’d be located. It was on the second floor of an old building in Beechview, and all it featured were windows, brick walls, and scattered pieces of wood, with one light in the middle. The city said, “You can be here, but you’ll have to raise the money to rebuild.” In time, we did, and it was a lot of work. While I was still studying for my master’s degree, the build-out took place. In those days, I was just one person — me — working with clients, and it was very intense. Consequently, I really didn’t have a life.

I actually started serving clients in 2017, in a tiny office on Broadway Avenue in Beechview. I had just a desk, basically. I received my master’s in May 2018, and the new space was opened the following year. Throughout, many people came to my office. They couldn’t believe that they actually had functioning food service and mechanic businesses, barber shops, and cleaning companies in the U.S. People sometimes came to me in tears. Some moms would say, “Back in my country, I watched movies and saw parents and children playing in their backyards. Now I am playing with my children in our own backyard. We are living in the house of our dreams.” That’s when it all clicked. This is why I ended up in Pittsburgh, to build a platform for economic development within the local Latino community. Everything came together: my training in management, entrepreneurship, marketing, IT, and international business. In my previous job, I was always traveling overseas to conduct business. Having been to many countries (and speaking four languages), I learned to understand how their economies worked and how people lived. Now I was in Pittsburgh, doing the same thing, and helping people to create sustainable businesses here.

Believe me, I didn’t do this for the money. When I joined the PHDC, I was living off one of my IRAs. And it wasn’t until 2020 that I had a part-time person helping me. Now, we have a staff and a group of consultants numbering 15 persons, four of whom are full time. But when you start to get a little older — I’m now 52 — you begin to ask yourself questions: “What is going to be my legacy? What is going to be my contribution to the world, to life?” Well, the PHDC is my contribution.

Many people come to our business incubator without capital, and I tell them that they’ll have to have some money to make some money. The training starts there. I don’t want to kill their dreams. I want them to stay with us and, when they’re ready, we’ll help them. Currently, we are working with nine financing institutions. An organization’s reputation is on the line when you go to a financing institution and they decide to invest. If it doesn’t work out, it’s going to be harder the next time. And when it comes to banks, many of which want access to the Latino market, I tell them that they must have bilingual people working at their institutions. Bankers must be able to communicate and interact with Latino people in Spanish, the language with which they’re most comfortable. I’ll say that they’re trying, however slowly.

As for our employment program, we’re simply a community and economic development organization that helps to connect employers with good candidates. When we started the program, we were bombarded by many employers who were looking for workers. I responded to their calls by asking, “Why are you looking for Latino workers?” They would say, “Because they’re reliable.” Essentially, I was doing research, trying to understand. “Reliability” is what employers see in Latino workers. Some people will have papers and others may not. But this is the United States, and we have been an immigrant country forever. People have always wanted to come here to provide a better life for themselves and their children. But, if you listen to certain community leaders, they like to say, “These people are coming to take our jobs.” So, tell me who wants to do the jobs they take? Who wants to be cleaning Downtown at night for $10 an hour? Who wants to roof houses in August? I could show you people who would take those jobs in an instant. The other thing I often hear is, “These people are working here and sending the money back to their home countries,” to which I respond, “They’re sending maybe, at most, 20 percent of what they earn per month. The rest of their money gets spent here.”

So, take a moment and ask yourself, “What is this country all about? Why has it done so well?” Because for more than a century, immigrants have come here, became entrepreneurs out of necessity, and created successful businesses. If we don’t make a way for the new wave of immigrants to do this, they can’t contribute to the economy. They’ll live on public assistance because nobody’s helping or teaching them.

At the PHDC, we are dedicated to improving the lives of Hispanic people who live locally. In my opinion, if we improve their lives, we create positive economic output for everybody. We aim to create good examples for others to follow. In fact, we have assisted businesses that started five years ago and are now million-dollar companies, employing 10 or more workers. Their families needed housing, and through our home ownership program, we’ve helped them to buy houses. As long as we provide opportunities for these people, they will want to stay here. If they stay here, they will invest their money. And if they invest, they will create roots, and the wealth they build will stay here as well.

It’s a fact that the government doesn’t want immigrants to have Social Security numbers or, in Pennsylvania, even driver’s licenses. Can you imagine how many people would be attracted to the state if we offered driver’s licenses to immigrants, as other states do? When I came to this country, all I had to do was show my passport and I got a license. How do you expect entrepreneurial people, with restaurants, food trucks, or whatever, to thrive when they can’t drive legally? Some of the companies that we’re helping can’t grow because they aren’t permitted to drive. These companies could grow and provide more employment (and tax revenue), but the state is limiting their growth.

I never wanted to build an immigrant program. What I’m interested in is economics. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we had to raise money to help many people and their families who didn’t have access to benefits. If we weren’t here, who would have raised the funds necessary to help these people pay their rent, for example? Remember, no one was obligated to stay in Pittsburgh. If a family was nine months behind on rent, what would have prevented them from moving to another state? The irony is that the current situation works to the immigrants’ advantage because, if they relocate, with no ID there’s no way to trace them. We helped some families pay rent because we didn’t want them to leave Pittsburgh. If, all of a sudden, many of these families started leaving, this town would soon feel pretty empty.

My mom, who passed away in 2015, was a strict woman. As a result, my siblings and I have all done well. We always say that it’s because of her and the tough life we had when we were growing up. When I look back and consider where I started, and where I am now, I feel a sense of satisfaction because not only have I been able to fulfill the dream of what I wanted to be, I also have fulfilled my life by doing something meaningful. And I pray that my contributions to society, to my culture, and to the people that I belong to, will carry on.