“Reviewing the following excerpts from some of the 40 first–person profiles I created for the magazine over the past 10 years was an emotional experience for me. How many people get to choose from among the most prominent individuals in their hometown and spend time with them learning their life stories? Some have passed on since the time we spent together and others have become friends. But I remember each and every one of the amazing people I interviewed for their good cheer and willingness to open up and share their personal stories with me. If it’s true that we are all but an amalgam of everyone we’ve ever met or known, I consider myself a very fortunate person.” — Jeff Sewald

Robert Qualters

Artist

Winter 2010

“What’s it like to be 75? Well, I’ll tell you. I’ve had two knee replacements. I’ve had back surgery. I keep falling down and breaking things: my fingers, my skull. But overall I feel pretty good, actually. I still like to work. I don’t give a damn about going to clubs, as I once did. It’s wonderful and natural for people younger than me to do that. Sure, I killed a few brain cells along the way, which was very important. That’s why you have so many of them to begin with. You know they’re going to get fried one by one—if you live life properly.”

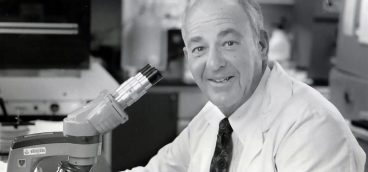

Cyril H. Wecht

Forensic pathologist

Spring 2011

“Sometimes comments come back, often snide, about my involvement in certain high-profile cases. Well, that’s what I do as a forensic pathologist. My work with the media hasn’t kept me from doing autopsies. There aren’t very many pathologists around who have done more than me, and there aren’t very many who, at my age, are still doing them—more than 300 a year. So my detractors can take their criticism and shove it.”

Arnold Palmer

Golfing legend and entrepreneur

Summer 2011

“My father, Deacon Palmer, taught us manners, how to act among people and, I guess, just about everything else we needed to know to get along in the world. But he was never one to lay a lot of accolades on you. So it was really something special when he said, “You did good, kid.” Starting at about 3 years old, I went to work with my dad, who was the golf course superintendent and greenskeeper at Latrobe Country Club. And I stayed at the golf course with him all day long. Among other things, we got to cut the golf course grass together on a tractor! Memories of that place and of those times are some of the best of my childhood.”

Jeanne Pearlman

Philanthropy executive

Summer 2007

“I was raised in Squirrel Hill. It was a close-knit community that valued ideas and intellectual activities. For my parents, dinnertime was not only about eating. It was also about talking, thinking and challenging. Any opinion expressed had to be countered with another opinion. My father would always ask, “Why do you think that?” This caused me to learn how to think. My parents insisted that I get more education than they had—to achieve more than they were able to achieve. I had to always do the right thing because they’d always find out, one way or another. And I had a responsibility to the world. I hope I gave that to my children. Time will tell.”

Paul O’Neill Sr.

Executive

Spring 2008

“Facts and knowledge have always been important to me, in government and in business. I believe that it is my duty to either know the answers or to know where to get the answers fast if an important decision must be made. In the earlier time that I was in government, there was a lot of weight given to facts and analysis and a lot less weight given to political ideology and that had a big impact on how we allocated money and how it was used. I think we’ve lost our way over time. What I see is a bipartisan slouching towards sloth.”

Chip Ganassi

Auto racing entrepreneur

Winter 2011

“In essence, what happens in racing is that you just get tired of breaking bones. At a certain point, you ask yourself, “What am I going to do when I turn 30?” When you’re really young, you think you’re bulletproof. But a couple of my friends died racing, a couple others got hurt badly, and a couple more are still limping around even today. Sure, I had a bad crash. So what? I consider myself very lucky—and I’d rather be lucky than good.”

Thaddeus Mosley

Sculptor

Summer 2010

“I think artists have a personal perspective, a vision—something they want to see. In my old age, a lot of times I don’t feel like cleaning the house or doing stuff like that, but I always, unless I’m sick, feel like going to the studio. I always believe that I’m going to do something better than I’ve done before. Maybe it doesn’t happen, but it is a challenge, and that brings personal satisfaction.”

Barbara Luderowski

Founding director, The Mattress Factory

Summer 2009

“This is an aberration for me, talking about the past this much. I talk mostly about what’s now—and the future. It takes a lot of time and energy to talk about the past. It’s much more interesting for me to talk about what you want to do, what you like to do, and where you’d like to go than it is to talk about where you’ve been. I face forward and go forward.”

David M. Matter

Businessman and civic leader

Spring 2010

“When I look back on my life, everything I’ve accomplished and everything I’ve become has been because of someone else—their advice, their giving me an opportunity. You just can’t figure things out or plan well enough to do it on your own. If you don’t have help—and some good luck—it’s pretty hard to succeed out there.”

Mark A. Nordenberg

University leader

Winter 2014

“My father was an only child born of Swedish immigrants, and my mother had one sister who had no children, so my brother, sister and I were the only grandchildren on either side of the family. All of my grandparents lived just across the tip of the lake in Superior, Wis., and we were very close. But when my father told us during the summer before my senior year in high school that we had to move to Pittsburgh because he was being transferred there by U.S. Steel, we were not happy. I still have images of the five Nordenbergs huddled together wondering what this big, dirty city to the east had in store for us. When we arrived, however, we loved it. Pittsburghers are the perfect blend of Midwestern values and Eastern spark, and without question, moving here was one of the best developments in my life. In a broad sense, it marked my entry into the larger world. Years later, when I went back to Duluth for a school reunion, I remember thinking about how things might have been different had I stayed there. Many people I had known were still in Duluth. They were married to each other and seemed happy, and I was glad for that. But I was also glad that I had moved on.”

Maxwell King

Philanthropy executive

Fall 2015

“I don’t think I’ve ever enjoyed anything as much as my time at The Heinz Endowments. I had already run a newspaper with a $90 million budget and had 650 people reporting to me, so I thought, “I know how to run an organization, and that experience will help me at the Endowments.” But when I got there, the experience that was critical was not managerial; it was my reporting experience, because grantmaking requires the gathering of information, understanding an issue or a problem, organizing, analyzing, synthesizing, and then presenting a response in a way that gets people excited and convinces them to coalesce around it. It’s like writing a piece for “Sunday, Page One.” So my reporting background was what I drew upon and what made the job a comfortable fit. The big difference was, if you’re a newspaper man, you do all of that, and then keep a distance. You’re not an advocate; whereas, if you’re running a foundation, you must embrace a cause and become an advocate for it.”

Ed Rendell

Public servant

Winter 2013

“Like most paths in life, public service comes with its pros and cons. The cons include a general loss of privacy, but I’ve been used to that for so long that it isn’t a problem. Another drawback is the incredible workload. I almost never have a day off. Then there are people’s expectations, which can get way out of whack. But the downside pales in comparison to the upside. I like interacting with and helping people. And even though I’ve been out of office for nearly two years now, people still come to me for help—not as a lawyer, but as an advocate—if they’re, say, having trouble getting a license renewed or getting the City of Philadelphia to clean a vacant lot. Sometimes all it takes is a phone call. My staff says, “Why do you do that? It’s a waste of your time.” But it’s what I’ve done all my life. Of course, I do get the “I’m sorry to interrupt your lunch, but…” routine a lot. But as I say to my friends, “Coal miners have to deal with getting dust in their lungs all day; all I have to contend with are people stopping me for my autograph, to ask questions, or to have a picture taken with me.” It’s an easy tradeoff. My son used to say, “It takes my dad three times as long as anybody else to walk a block.” But it’s a small price to pay.”

Elsie H. Hillman

Political and civic leader

Spring 2014

“Before I was married, I didn’t think too much about where I was going. Life just sort of happened for me, and it happened in a good way. As for Henry, he worked hard to become as successful as he’s become. His family was not poor to begin with, of course, but it was nowhere near as prominent as our family is today. He made the Hillman Company what it is. He’s a good decision-maker and is painfully honest with himself and other people, too. Sometimes, when we write out a large check from one of our foundations to a worthy organization, I think to myself, “How is it that we are able to do such a thing?” Like Henry and I, and our kids, other Pittsburghers of considerable means must learn to be concerned about what’s going on around them in their community. We don’t live alone. None of us are islands. We must pay attention to the needs of others. After all, that’s what community is about.”

Sala Udin

Community organizer

Fall 2013

“As a kid, I’m not sure that I was aware of my “African American-ness.” Public housing was a communal setting—24 families in one building facing 24 families in another—and every day all of us kids poured into the courtyard, which served as our playground. We became each other’s siblings, and all of the parents in the community became our parents. There were no white folks around, so the contrast that would have made us aware of being different was not there. In any case, my earliest awareness of being black came around seventh or eighth grade. I went to school one day and noticed some kids huddled in a circle looking at a magazine. I figured it was probably a girly magazine so, like any other boy of 11 or 12 years of age, I rushed over to look. Actually, the kids were studying a picture of a boy that looked very much like us, only a bit older, who was laid out in a casket with his head swelled-up twice its normal size. According to the magazine, he had been lynched in Mississippi because he “whistled at a white woman.” That boy’s name was Emmett Till, and I had never seen anything that graphic before. I wondered why his mother had allowed him to be photographed that way, in an open casket. Was she trying to tell us something? Well, the whole thing scared the hell out of me. Aside from my days at Holy Trinity, when the nuns rubbed my head for good luck and called me “Little Black Sambo” (my given name was Samuel Wesley Howze), that encounter with the story of Emmett Till was the first time I really knew that I was black.”

Allan H. Meltzer

Economist, professor, author

Spring 2015

“I went to college thinking I was going to become a lawyer, but I took a course in economics and liked it. Then I took more. When I graduated from Duke with a bachelor’s in economics and moved to California in the summer of 1948, I started to work with the Progressive Party there. That proved eye-opening. The membership wasn’t the least bit interested in civil rights, as I was. They seemed interested primarily in defeating the Marshall Plan and promoting a pro-Russian foreign policy. That changed me. I slowly became a Libertarian, and I remain so today. The question for me always was, “Are we as a people better off having others direct us or are we better off directing ourselves?” And I came to believe strongly that, while we would make errors either way, we’d make smaller errors if we directed ourselves.”

Thelma Williams Lovette

Social worker and community leader

Spring 2009

“One thing that I know is true is that we all need each other. If you have something that you think will benefit someone else, share it. That’s what I believe. I think that philosophy came from Mama and Papa because we were always taught to give something back. You know, my mother always wished to visit Africa to see where we came from. And we’d all say, “Mama, you don’t really want to go back there, do you?” Then she’d say, “Yes I do. I want to find out what it was like.” For my 90th birthday, my daughter took me to Africa. What an experience it was! I stood up on Table Mountain in South Africa and looked up to Heaven and said, “Mama, I’m here. And it’s beautiful.”

Andy Russell

Businessman and former Steeler

Spring / Summer 2006

When Chuck Noll took over the Steelers in 1969, we weren’t a good team. We worried about having a loser mentality. But having watched our game films, Chuck told us not to worry about that. He said, “You’re good people. You’re going to be good citizens. Unfortunately, you can’t run fast enough or jump high enough, and I’m going to have to replace most of you.” Only five of us survived the march to winning the Super Bowl in 1975. When you consider people who are successful, they almost always have great attitudes. They are also driven to work hard. Chuck Noll used to say, “Life is a journey—and you never arrive.” You shouldn’t want to arrive. Once you think you’ve arrived, you’ll stop pushing to get better.”

Joe A. Hardy III

Entrepreneur and civic leader

Winter 2007

“Money. That’s your scorecard. Absolutely. But anyone who is financially successful is so because of the contributions of many people. I don’t say that because I’m a good guy. I say that because it’s true. When you’re young, you’re always looking over your shoulder. But when you get to my age, there’s one good thing: You don’t worry about too much. You just get up there and do what you can do, and if people don’t like it, to hell with them. I’m certainly eccentric. But I don’t try to be. Maybe I just look at things a little differently than most people. Look, nobody ever gave me a nickel. I started with peanuts. My folks had a little bit of money but I said, “I don’t want any of it.” So I guess that all I can hope for is that, when people think of me, they think, “Hey, that jackass started out with only $5,000 and made a fortune. Maybe I can, too.”

Ted Pappas

Impresario

Winter 2015

“My parents, God bless them, were nurturing people, but were more interested in scholastic achievement than in personal expression. Part of that was their immigrant experience. They wanted to make sure that we were safe and secure before we were “fabulous.” And, as you might guess, they did not like my choice of career. The theater was too insecure and, to them, undignified. It was a waste of what they considered my potential. In their eyes, it could only lead to unhappiness. They were not concerned so much about success. They were more concerned about honoring one’s gifts. They kept hoping, even after I had some measure of success, that I would finally come to my senses. For me, a life in the theater became a very private and personal journey. It was something I did on my own and, I think, for that reason, if for no other, it has remained precious to me. It’s something that I chose to do despite resistance. When you are optimistic, as I was, you open your life up and many great things can happen.”

William E. Strickland Jr.

Educator and activist

Fall 2014

“I guess I’ve always wanted to make something of myself, and that’s mostly because of my mom. It wasn’t so much what she told me but what she allowed me to do, because once I got into clay, I took over the basement of our house, turning it into a studio. Then I commandeered the laundry area and fashioned a dark room for my photography. My mom supported everything I did, even when I went to the South on my own to work for civil rights. She let me explore life, saying, “I’m with you, Bill, and I’m proud of you.” When I was invited to the White House for the first time by President George H. W. Bush, I saved the invitation and the menu from the luncheon, brought them home and gave them to my mother. She teared up, saying, “I never thought that one of my children would break bread with the President of the United States.” I told her, “The reason I was able to do that is because of you, and all the time, energy and belief you had in raising me the right way. Thank you, Mom, and I love you.”

Jacqueline C. Morby

Businesswoman and private equity investor

Summer 2012

“I went to see Microsoft when they were about $5 million in sales—and, yes, I visited Bill Gates. When you’re visiting companies, one of the things you judge as a venture capitalist is how their offices look. Microsoft was a bit of a mess, with boxes and lots of computer equipment strewn about the place. When I got there, a kid came and told me, “Bill isn’t in yet this morning, but he’s going to be here at some point, so just wait.” Finally, about an hour later, Gates came in looking frazzled. “I’m really upset this morning,” he said. It seemed that he had been pulled over by the police while driving back from the airport the night before. He was also unnerved by some business challenges, about which he went on and on. But then he started outlining his vision for Microsoft, and it was impressive. I planned to bring a partner out to see him, maybe a month later, because the company was so exciting and profitable. But at the time, we were working on another big deal and learned quite suddenly that one of our competitors was doing some courting as well. So we made the difficult choice to postpone meeting with Microsoft to try to rescue our other deal. During the month-long delay, sadly, another investor stepped in and locked up the deal with Microsoft.”

Richard V. Piacentini

Botanist and innovator

Summer 2014

“I had polio as a kid and because of that I was not really good at the kinds of sports that one normally would play in high school. That, combined with the fact that I was shy, meant that I wasn’t very popular. But when I was around 12 or 13, my parents signed me up for sailing lessons and I really excelled at it. I was the skipper and my brother Kevin was the crew. One summer back on Long Island, there were 14 local regattas and my brother and I won 12 of them. (In the two we “lost,” we actually tied for first.) That year, the nationals and the North American championships were set to take place in Massachusetts. We thought about entering, for about a minute or two, but then decided to forget it. It was inconceivable to us that we could win anything like that, so we decided not to go. But two guys—whom we consistently beat all summer long—did enter and came in first and second in the nationals and third and fourth in the North Americans. To this day, I wonder, “If we had gone, would we have won? If so, how different might our lives be today?” Of course, we’ll never know. But that experience stuck with me. That’s why I decided I had to go for the career I wanted. I didn’t want to be asking myself forever, “What if?”

Dan Rooney

Steelers owner and U. S. Ambassador

Spring 2012

“Another big problem we have in the world in general these days is the influence of big money, and the NFL is no exception. When the league entered into its first television network arrangement way back when, the money was huge. We went from making like $150,000 a year to maybe $1 million—a big, big increase. Of course, we all were very happy about that. But my father said, “You’ll rue the day that this happened. Before long, these very entities will feel entitled to tell you how to run your business. TV people will be telling you how, when and at what time to play.” And that’s where we are, pretty much. Money never influenced my father’s decisions. He didn’t do things just because of how much he would earn. He did things because they were the right things to do.”

William S. Dietrich II

Businessman and philanthropist

Winter 2012

“When I graduated from college, I felt a great hunger to achieve. I always thought that Princeton had an air of snobbery to it so I said to myself, “Fine. If achievement is all about money, then I’ll show the bastards. I’ll get the money.” I’ve always been a workaholic. I love to work. But this focus on monetary gain is, unfortunately, what we are all about in this country these days. Life has become a game of acquiring more and more. But once you reach a certain point, then what? For so many people, no amount of money will ever be enough, and that creates a lot of problems, for those individuals and for the country.”

Dick Thornburgh

Lawyer and government leader

Fall 2010

My father passed away while I was in college, so my mother supported me through law school. Afterward, I worked for a couple of years in the legal department at Alcoa. Then, in 1959, I took a job with what is now K&L Gates. By that time, my wife and I had three boys and things were looking pretty rosy for us. On July 1, 1960, however, my whole world was turned upsidedown. My wife was killed in an auto accident and my youngest son, Peter, aged 4 months, was seriously injured with multiple skull fractures and extensive brain damage. The accident changed my entire outlook. At 28, I learned how fragile life can be and how limited our time is to do something useful with it.”

David McCullough

Author, narrator, historian, lecturer

Spring 2013

“To me, one of the most infuriating ideas that is commonly expressed by supposed wise men and women is that other days were “simpler.” There were no simpler times. Would you like to have lived in the midst of the Civil War? How about World War I? How would you like to have suffered through the influenza epidemic of 1918 or the Great Depression? Those were not simpler times. They were different times. And we must understand why they were different and why the people who lived through them were different. No matter what some may tell you, those people weren’t “just like us.” To write or understand history, you must try as best you can to put yourself in the shoes of those who lived in those other times. You have to marinate yourself in your subject, in the time and place. You have to go where things happened, walk the streets, smell the air, and hear the voices.”

Patrick Gallagher

University of Pittsburgh chancellor

Summer 2015

“My view is that what sets us apart from all other creatures is that we are toolmakers extraordinaire. We have always adapted to the tools we’ve made, and they have changed us: tools of industry and commerce, communication and computation, and tools of war and peace. They’re all part of the human story. And that’s why I think that technology doesn’t erode our humanity. In many ways, it accentuates it. Can we understand how these new technologies will change the way we think and live? I believe the fact that these currents are moving through the university and through our society make it a magical time to be alive. It’s exciting to live in a time of great change, even though it’s unsettling when big questions are being asked. That’s not scary for me. I think that it’s out of this kind of chaos that the biggest ideas and advances always come.”

Edgar Snyder

Attorney

Fall 2012

“My brother, the physician, was truly the pride of our family. And I was determined to make my parents proud, too. Unfortunately, when I went to Penn State and got a “C” in chemistry, my hopes for a medical career were dashed. But I remember, at the time, having a conversation with my mother, who was a very funny person with a great a sense of humor. She said to me, “Edgar, if you can’t become a doctor, you should become a lawyer because you’ve got the biggest mouth of anybody I’ve ever met.” She was right. I could argue about anything. At Penn State, I put my big mouth to work as a member of the debate team. I was captain for two years, competed in different parts of the country and, as a result, was able to hone my ability to speak and to think quickly. My strong suit has always been the ability to articulate concepts and ideas, not my intellect. Given my big mouth and ability to articulate, law school did indeed seem right for me. So I went to Pitt for law school and was truly lucky to survive, graduating near the bottom of my class. That’s the truth, and I don’t try to hide it. It serves many people well to understand that you don’t have to be a top student to become something in life. It’s what you choose to do and how hard you’re willing to work at it that counts.”

Manfred Honeck

Music Director, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

Fall 2008

“Every human being develops in his or her own way. I’m sure that I am a little different from my parents, and also from my brothers and sisters. But because of my faith, I began to understand early that it would just not be possible for me to live in this world happily without thinking of others. One can decide to be an egoist or one can decide to encounter the world with open eyes. If you do the latter, you will see the wonderful creation around you. You will also see the challenges you will likely have to face in time. We all go through good times and not-so-good times. That is life, for everyone. We must embrace it all.”

Jared L. Cohon

University leader

Summer 2013

“For the past 16 years at Carnegie Mellon, I have called myself the “Accidental President,” or the “Forrest Gump” of university administrators, and there’s a lot of truth to that. At almost every step along the way, when opportunities arose, I simply didn’t say, “No.” I never sought to position myself for any job. After all, life is really about the journey, which often makes a mess of one’s plans. So when students ask me, “What must I do to become this or that?” I set out to destroy whatever ideas they have about life plans, because I don’t believe in them. I tell them to enjoy and focus on whatever it is they’re doing at the moment, and the next step will become apparent.”