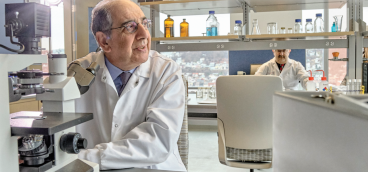

What Do I Know? Dr. Kathy Humphrey

I was tenth in a family of 12 children. My mother was a secretary and seamstress. My father was a bricklayer who was in the Army and stationed in Shreveport, Louisiana, where he met my mother. This was at the time of “Jim Crow” and, after my father’s discharge from the service, my parents moved from the Deep South to Kansas City, Missouri, where I was born.

My parents moved to the Midwest with the hope that their children might have a better opportunity for an education. If you read the book The Warmth of Other Suns, about the six million African Americans who moved from the South to the North and West between 1915 and 1970, you will see that my parents’ relocation was a natural progression for black families at that time. It wasn’t until I read that book that I realized my family was a part of what is called the “Great Migration.”

In Kansas City, we lived in a predominantly black neighborhood, as most African Americans did in those days. The Civil Rights Act had been adopted in 1964. I reached the age for kindergarten in 1968, the year that Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, after which desegregation became the thing to do. All black children in my neighborhood, up to my street, went to the neighborhood school. The children from my street and beyond were sent to white schools.

I attended kindergarten in the afternoon and had to catch a city bus, all by myself, in the late morning. I’d ride out to the white neighborhood and then had to walk a couple of blocks to school. My mother’s theory in life for her children was, “You must do everything that you can for yourself. I will do the rest.” So, I went to school by myself every day and didn’t feel any way about it. Such independence was normal for my family. But I was always excited when it rained because, if it did, my father couldn’t work. As a result, he would show up at the bus stop, pick me up and take me to school. That was always a delight and is probably why I don’t mind the rain so much, even to this day.

In kindergarten, I struggled at the white school because the other children wouldn’t play with me. I was different. I was strange to them. I didn’t live in their neighborhoods and I didn’t come to school the same way they did. I complained to my parents about this, and I remember hearing them talk about whether they should move me back to the neighborhood school. They decided not to do that because they believed it was important for me to learn to survive in that world, and I’m grateful today that they didn’t make me change schools. The experience taught me how to live in two different worlds, and to communicate in two different ways, so much so that my father used to say to me, “You’re going to make it, Kathy, because you understand how to communicate with white people.”

At the time, I had no idea what my father was talking about. I didn’t realize that I was moving back and forth between one culture and another. But I did know that when I heard either of my parents talking on the phone, I could tell if they were talking to a black or a white person. I didn’t know until years later what an amazing job my parents did in helping me to understand that, while there were some hostile and difficult white people, there were also many very good and kind white people. That’s a lesson the whole world still needs to learn. Goodness has nothing to do with the color of one’s skin.

Fast forward a few years later, when desegregation programs were being abandoned and black students like me were being sent back to our neighborhood schools. By that time, I was at an age where I could tell that schooling in our neighborhood was dramatically different from schooling in white districts. We didn’t have the same supplies that the white schools had. We didn’t have the same books. Nothing was new. Everything was used, and it definitely was not equal. Right then, I learned that the white world and the black world were not the same, which was a dramatic thing to learn as a child.

My parents were very forward thinking, and education was crucial to them. They were willing to make great sacrifices for it, and it made me grow up fast. I was independent in many ways and comfortable in different situations. In school, I sought out many student leadership positions. A person had to be fearless to do that, and a lot of my fearlessness came from my mother and father. They were always clear because when you have as many children as they did, you have to be regimented and organized to function. Still, I used to say to my mother, “When I grow up, nobody’s going to tell me what to do,” to which she would reply, “Kathy, somebody is going to tell you what to do for the rest of your life. If nothing else, you’re going to have to obey the stop signs.”

Eventually, my parents decided that they wanted me to go to college, so they bused me back to a white school to begin junior high, and I stayed there through high school. By that time, integration was the rage and there were other black children at white schools. But we were still a minority. And the races were still largely separated so I didn’t get the education that I should have. It was not a place that made sure that poor black children were successful. I had good grades, but really wasn’t pushed to learn what I should have been learning at that point in the game.

Nonetheless, in high school I became a youth leader for my church. And I also joined Girl Scouts, which taught me the value of networking. I was extremely competitive when it came to cookie sales. But I quickly learned that, to sell a lot of cookies, I needed to know everybody on my block. From time to time, I would stop at the older ladies’ homes and sit on their porches and talk with them. And those women bought tons of cookies. From this, I learned that, if you establish relationships, people will help you and work with you. So, I started building a network in my neighborhood and in my church. I made sure to know who the people were and how to care for them. And that care always came back. You didn’t know where or when, but it did.

All my life, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about “next steps”: “How is what I’m doing now going to help me to do the next thing?” What I had been doing all along was making sure that I was prepared to take the next step I was called to take. My spiritual life is the guide. I have incredible faith, and I rely on that. It is my center. It is how I move. Because of that, I never doubted that I was going to get where I wanted to be.

People in my church helped build me, too. It was an historically all-black church in the 1970s and, amazingly, it offered me a $1,000 scholarship to go to college. Forty years ago, that was a lot of money. My church not only gave me financial assistance, but it also provided opportunities for me to sharpen my speaking and leadership skills. One woman in my church actually filled out the financial aid papers every year for my parents. Another woman bought my school supplies every semester. I don’t know what those women saw in me, but they invested in my life. People opened doors for me. I just had to walk through them.

For college, I first went to Central Missouri State, which was a medium-sized school located about 45 minutes outside Kansas City. My parents wanted me to go to the University of Missouri, but I didn’t want that because they had “gang showers,” and I couldn’t imagine showering with other people. So, I chose Central Missouri because it had dorm suites, and I only had to share a bathroom with four other people. Not satisfied, I soon learned how I could get my own room and, by the second semester of my freshman year, I was the RA, or “resident assistant,” on the floor of my dormitory.

I then became supervisor of the RAs during my later undergraduate years. People said, “You know, Kathy, you could do this for a career. You could be a hall director.” I thought, “Yes, I believe that I could do that.” So, while I went to school to become a teacher after finishing my undergraduate studies, I decided to continue on to get a master’s degree and become a hall director. Before long, I was working full time at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, where I met the man who would become my husband. He’s a man of faith, and his faith is important to him. He was very easy to talk to, and to get along with. And he was very committed to things in life that were important not only to him but to me, too. That’s how we got together.

My husband was at Faith Baptist Bible College while I was at Drake, and we met each other at church. I don’t believe that there was a time when we didn’t think we were going to get married. Within the year we were and we moved back to Kansas City. I studied at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and finished my master’s degree. After that, I headed back to Central Missouri and worked there for several years, moving up the ladder. Before long, my husband and I moved to St. Louis University, and I became director of housing, an associate vice president and then, ultimately, vice president of student affairs. I got my PhD there and was introduced to Catholic education by the Jesuits. I had a lot of admiration for the Catholic approach to children and schooling, but I had no idea that this would become important later in my career.

My husband and I did a lot of moving throughout our marriage and, along the way, we were foster parents for several children. We adopted the last two and got them when they were just four days old. Now, we weren’t originally going to adopt. My husband was working at a hospital at that point, and he said, “Kathy, there’s a woman at the hospital who’s going to give birth to twins and has decided to give them up. We should think about adopting them.” And I said, “I don’t need to think about it. I don’t want to do babies.” We had been married for about seven years at that point. I wanted independent children, like I had been, but my husband persisted.

We were living and working in a small college town. These were African American babies, so the chances of somebody adopting them, in any case, were slim. And the fact that they were boys made their chances of being adopted even less likely. But my husband was determined, and my mother convinced me that, given that my husband had been so good with all our foster children, I should give it a chance.

Adoption is a straightforward way to walk into parenthood, but it took me a little while to get used to it. However, once we had our boys, we just loved them, took care of them, and knew we would have them forever. I never felt so fulfilled yet vulnerable. Children have a way of showing you who you are, flaws and all. They make you humble.

My husband is a chef and, for a while, we had a little restaurant in St. Louis. But when it came time for us to move again, this time to the University of Pittsburgh, we closed that restaurant. It’s true that my husband has made a lot of sacrifices for my career, and I don’t think I could have been a mother and a professional without his support.

When I agreed to come to the University of Pittsburgh, I said to the leadership, “One day, I want to be president of a university,” and I stayed at Pitt for 17 years, learning all that I could. I told Provost Jim Maher and Chancellor Mark Nordenberg, “I want you to make sure that I have the tools, the knowledge, and the vision to be a university president.” They promised that, if I would help them create a successful and engaging student experience at Pitt, they would make sure I was ready to achieve my goal. And that’s what they did. But where?

At the time, I knew nothing about Carlow University, but I learned that the school was looking for a new president. Fortunately, it was just down the street from Pitt. When they called me, I said, “Give me some time to learn a bit about you and I’ll call you back after the Christmas break.”

So, I took time during the break to learn as much as I could about Carlow, what they do and what they stand for. Carlow is a Catholic University, which is good because I had come to believe in Catholic education. I also liked the fact that Carlow was created to provide education for Catholic and Jewish women. And when I learned about the founders, the Sisters of Mercy, I identified with them. These were gutsy women who believed they could do the impossible. They were committed to providing opportunities for the least among us. I thought, “That’s who I am.” And when I learned that 40 percent of Carlow’s students were the first generation in their families to attend college, it sounded like a perfect fit for me, so I decided to jump in and go through their process. I said to my husband, “This is the place I should be because of the work there is to do.” Carlow was founded with a mission to create a more just and merciful world, and on that, we were in sync. I have always believed in trying to bring people together and help them to respect humanity. Together, people can do great things. Our students could be spokespeople for what is good and right.

At Carlow, we are extremely committed to workforce development. Many of the innovative programs that we’ve designed in recent years have been centered around this. Now, when I go out to employers, I ask them what they need and how we can meet that need through our curriculum. We have worked to fill holes in the regional workforce with new majors, and this strategy paid off. In a time when many institutions are struggling with enrollment, we’ve seen an 18 percent increase over the four years I’ve been here.

One of the best days of the year for me at Carlow is commencement. I always ask the students, “If you’re the first person in your family to go to college, please rise.” And when half of them stand up, it’s amazing to see. Then I say to them, “You have changed the trajectory of your families. You are now a symbol that a college degree is within reach. Many will follow you and do it, too.” To know that you have increased the social mobility of a group of people who couldn’t have imagined moving in that direction is thrilling for me.

This year, I presided over the graduating class that came to Carlow when I arrived. It was exciting to have been with a group of students for their entire time at Carlow and to see them cross the finish line. To do so takes grit. It takes guts. And it takes discipline. That’s what I love about this university.

At Carlow, we talk a lot about mercy, the definition of which is to be willing to walk into the chaos of others. The chaos that we see today has always been a part of our world. But as responsible humans, we must be able to walk alongside it while trying to promote equity and justice. We must keep the humanity piece in play, and for our students not only while they are with us, but more importantly, after they leave.

I’ve worked in higher education for more than 40 years, and I will tell you that the students here are the kindest I’ve ever known. When they arrive, we say to them, “We’re not going to just care about you. We’re going to love you. And we’re going to take on the wholeness of who you are.” While we are 80 percent female, and 20 percent male, today we’re engaged in bringing all kinds of students to Carlow. What is wonderful is that our students come here because they believe that we will care for and love them. They believe in the power of creating a more just and merciful world. It resonates with them, and they are drawn to it. They’re getting their degrees to be of service to others. And that’s very unusual in the world today.