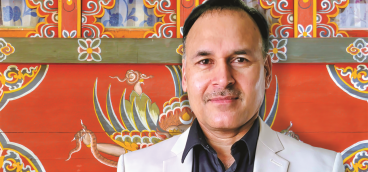

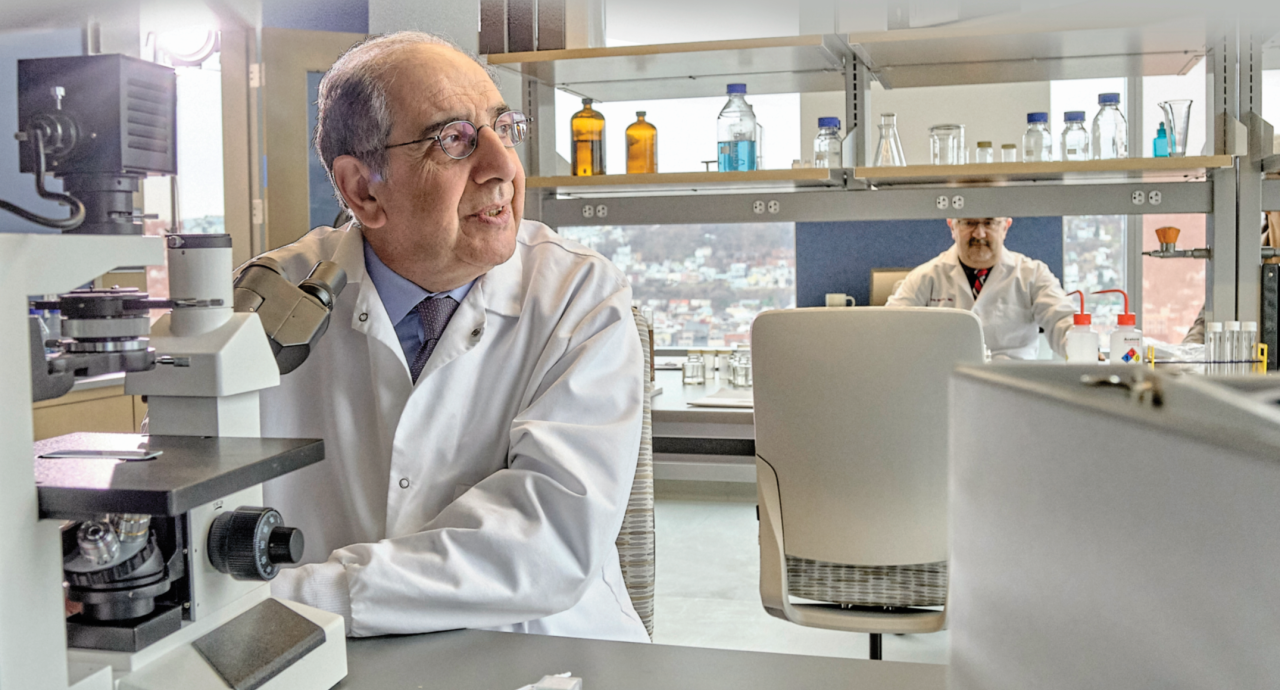

What Do I Know? Dr. José-Alain Sahel

I was born in Tlemcen, Algeria, a small city on the border with Morocco. My family is Jewish, of Spanish ancestry, and had been in Algeria for centuries. Both sides of my family were poor and struggled often just to eat.

My grandfather on my father’s side was severely injured during World War II and was left for dead on the battlefield. When troops came to gather up the corpses, he was among them — but he was still moving! So, they transported him to a hospital and informed his wife that her husband was dead.

Dr. José-Alain Sahel

Ophthalmologist

“Try again. Fail again. Fail better”

- Distinguished Professor, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

- The Eye and Ear Foundation Endowed Chair

- Chairperson, Department of Ophthalmology, UPMC

- Director, UPMC Vision Institute

- Emeritus Professor, Sorbonne University, Paris

- Adjunct Professor, Carnegie Mellon University, Hebrew University, and Honorary Professor, University College, London

My grandfather had to endure many operations. He was disfigured and yet, somehow, he survived. One day, after more than a year, he returned to his family, and, in time, started to make furniture again. It took him months to produce one piece, which he would sell for money enough to feed his family for a few days. Then he would work for several more months to make another piece to sell so his family could eat for another few days. He was a very brave man with a strong will to live and a deep sense of honor. My grandmother would fast several days a week to spare food for her many children.

My parents managed to become educated, and both became teachers. The values they instilled in me were those of knowledge and education, both as a means of helping people. But when I was 6 years old, Algeria’s War of Independence from France made life unbearable in our homeland.

My father thought that all people should be respected, no matter who they were or where they came from. But this was not something that, at the time, many people in Algeria would accept. And as the nation descended into civil war between its divergent communities, terrorism came from all sides. Neutral people like my parents who supported human rights were targeted, so much so that they bombed our house several times. Because of this, one day, we left the country — urgently.

First, we moved to a small city called Rodez, in south-central France, where my father worked as a public servant. The city’s climate was cold, but it was full of nice people. We arrived at midnight in December 1961. The next morning, at 8 o’clock, we were at school. My parents insisted that we go, even after enduring such a long journey, and with no place yet to live. This, among other things, I believe, is what made me who I am. There was never an excuse for not working. We had to do it, so we did.

My family was always focused on sharing and explaining values to ensure that people understood each other. But for us, at that time, life was tough because we had abandoned almost everything in Algeria and had to begin again. To make matters worse, my grandfather on my mother’s side suffered a stroke after learning that his son may have been killed in a bombing back home. The stroke rendered him paralyzed, but he was a lovely person. I used to stay with him for hours because he was still able to speak, and I heard a lot of interesting stories about and from him, all inspiring. We took care of my mother’s parents because they, too, had left almost everything behind in Algeria. We lived in a small apartment, all my family, for what seemed like a long time.

Eventually, my father got a position in Marseille in southern France, which was about a four-hour ride southeast from Rodez. Marseille was a nicer place because the climate was more like that of Algeria: warmer, with more sunshine, and on the seashore. It was there that many of my family members managed to re-engineer their lives. They were able to rebuild by working in small public service positions, as teachers or as postal workers; jobs like that. But, as always, life was about going to school and learning. My family’s dream was to have one of us become a physician. I knew that, but did not think that I would become one.

In school, I excelled in math, physics, and philosophy. Everyone thought that I should pursue a career that required excellence in these disciplines because, in France, a “golden pathway” exists if you perform well in these subjects. So, I applied to and was accepted by the best program but realized, the day before classes began, that I did not want to be a mathematician or a physicist. I didn’t want to spend my life in isolation in an office, solving equations. I wanted to be engaged with people and thought that perhaps medicine would be a good path for me. Medicine might allow me the freedom to address and understand the human challenges of life, as well as the scientific component, at the same time. So, it was on to Paris University’s Medical School where, unfortunately, I learned that medical education was not at all about understanding. We were just there to learn and learn, and were never given time to understand what we were learning. Still, the scientific side of my mind wanted to understand. Consequently, at that point, I was disappointed with my medical education, but didn’t want to give up. So, I continued.

Early on in medical school, I became frustrated and asked many questions. I was often told, “Don’t bother; it’s not important.” Then one day, I found in a bookstore a dictionary of “topography and clinical diagnosis.” For every symptom, there was a list of many things to explore before prescribing treatment. I read about everything and tried to analyze conditions step-by-step to make sure that I didn’t miss anything. Then, one day, my mentor said to me, “José, I don’t think you are going to be a good physician because you ask too many questions. Just apply what you know.” But I just can’t work that way. I was always concerned about the patient’s experience. People thought that I was too slow or too thorough. So, they labeled me a failing medical student, even though I was at the top of my class. In the clinical setting, no one believed that I would make it. But eventually, I did.

It took a long time for everything in my work to fit together — dealing with people and trying to provide care, while also gaining an understanding of what I was doing. The challenge for many physicians is that we are taught to apply recipes to treat health conditions, and I am not a good cook. I couldn’t just mix tried-and-true ingredients and wait to see what happened. I wanted to understand those ingredients and how they might be combined with other ingredients to achieve better results for our patients. This had to be based on science.

So, I was a medical student first and discovered, much later, that it was possible to do clinical work and research simultaneously. I did rotations through many divisions, including pediatric oncology. That was in 1976, and many children were then dying from cancer. At that time, the chemotherapy that was being prescribed wasn’t working. After treatment, many kids came back to us worse off and were sent home to die. This was a lot for me to take. But, in time, a new combination chemo treatment started to work for some kids, and it was very moving to see them come back healthier, unexpectedly. So, I decided that what I wanted to do was clinical work and oncological research.

Soon thereafter, my wife and I learned that we were going to have a baby, so I accepted a position as a resident at the Adolphe de Rothschild Ophthalmology Foundation in Paris, where I was given the choice of specializing in radiology or ophthalmology. A friend of mine wanted to do radiology, and asked me, “Will you give up on radiology so I can do it?” I said, “I don’t care. This isn’t what I want to do, anyway.” So, I got into ophthalmology, only by chance.

When I started in the field, the work was challenging and the department chair asked me, “Do you really want to be an ophthalmologist?” I said, “No, I want to be an oncologist, but I’m pursuing this for now.” So, I had a tough time from the start. But eventually I discovered that ophthalmology is largely neuroscience. It was a beautiful and stimulating medical and surgical field, and I decided to continue with it. I would be an ophthalmologist and do research simultaneously.

As physicians, patients invest a lot of trust in us, and we need to earn that trust. They offer us the most precious thing they have — their lives — and we must meet their expectations. It’s a daunting task. When they come, they ask specific questions and most often, we don’t know all the answers. But the fact that we don’t know does not free us up to say, simply, “Sorry, but we can’t do anything for you.” We must engage in what is called “translational research,” which means to take a holistic question from a patient and translate it into a scientific question and then go to the lab to collaborate with scientists to try to build an answer. We will then evaluate the answer and work with the patient to try to deliver a positive result. Our job is to find answers and, often, we don’t. But when we do, it is gratifying when the bumpy road to get there makes sense, suddenly.

I never think that giving up is the right way to go. Patients are always dealing with a lot of stress and, as a result, strive to regain their well-being and comfort. But they are not well, and they are not comfortable. If you want to prioritize well-being and comfort, don’t become a physician. Often, you won’t sleep; you’ll worry. And if you don’t, there is something wrong with you. I’m not saying that we should be unhappy all the time, because there is a lot of profound joy in this work. The definition of joy for me is when I have overcome some barrier. I think educators should be like that. They should help students to grow beyond known borders. People should not be bound by wherever they are and should not feel that there is a limit to what can be done. We should never accept that. As physicians, we can truly help people and change lives. We have the opportunity, within a few minutes, to get into the middle of the lives of many wonderful people. We become members of their team, and are a part of their story, which is exciting.

I’ve been working with some families for decades and have many stories to tell about them. For example, one of my patients was blind from a condition called “retinitis pigmentosa.” He was in Paris and traveled to the Louis Pasteur University Hospital in Strasbourg, where I served as an ophthalmologist for my first 20 training and professional years. At that time, there wasn’t anything we could do for this patient, but I told him, “We are working on an artificial retina, and I don’t know how long it’s going to take; most likely, 10 years or more, before it can be tested on patients.”

Years later, when we were ready to test an artificial retina, we reviewed a list of patients who might benefit from it and were reachable. One of my collaborators produced a name and said to me, “This patient is a very good fit. You saw him in Strasbourg, years ago. He fits the criteria exactly.” So, he called the patient, who said, “That’s amazing because, almost exactly 10 years ago, I met with Dr. Sahel who told me that maybe in 10 years he would have something for me. And you have called me today to tell me that it has happened.”

The artificial retina worked for the patient for a couple of years before it started to malfunction. But he was one of the first in Europe to benefit from our work. Unfortunately, not everything works forever. Many things fail, and we must address that. Sometimes we face impossible situations, and may spend 10, 20 or 30 years developing a new therapy. Today, one of my projects — 30 years in the making — has reached the clinical stage. It took all that time to get things right, from the hypothesis to the clinic. But the help it will offer our patients justifies the effort and the journey.

Through the years, I was successful in France and did a fellowship at Harvard, became a full professor in Strasbourg at age 32, and created, from scratch, my first laboratory. I was seeing patients and doing surgery all day, tried to see my wife and children in the evening, and worked in the lab at night and on Sundays. After a few challenging years, our small group started to publish promising articles in top journals. I then rose to be chair of Quinze-Vingts National Eye Hospital in Paris (which was established in the year 1260) and founded the Institut de la Vision. My Strasbourg lab team, which had grown from a few people to around 40, decided to follow me to Paris. We founded an international institute of 300 members, attracted from more than a dozen countries. We successfully developed several breakthrough therapies, such as prostheses, gene therapy, neuroprotection, optogenetics — all of which led to the creation of multiple start-up companies and the launch of several first-in-human trials. But in 2012, in a Jewish school in Toulouse, a terrorist killed three young children and several other people, and I noticed that the story received little attention. I saw a picture of the kids who were killed and thought about my own grandchildren, and about our family’s history. Some of us died in Auschwitz. So, I said to myself, “This is not going to happen again. Jewish kids are being killed, and nobody cares.”

In 2015, a series of terrorist attacks took place in France. On a Wednesday evening, a Muslim friend and colleague of mine came to meet with me, and he looked terrible. So, I asked him, “What’s going on?” He said, “Didn’t you see the news?” I hadn’t; I was too busy working. “There was a terrorist attack very close to the hospital and several journalists were killed,” he said. “The terrorist was an Arab, and I feel horrible about that.” I said, “It’s not your fault. It’s just the work of some terrible, crazy people.” The next day brought another attack, in which a police officer was killed — close to where my granddaughter went to school. The following day, there was another attack, this time at a Jewish food store. So, I started to think, “Am I going to spend my time watching the news constantly?” The public reaction to the terrorist attacks concerned mostly the journalists, not the Jewish victims. I thought, “We don’t really belong to this society. We are just marginal here,” and I began to consider the next step for my family.

For years, I had been receiving job offers from all over the world, but my wife wanted to stay in France. She never wanted to live in the United States and preferred to raise our family in France where all could receive a good European education. But I insisted. “I don’t think there’s a future for our grandchildren in this country. We must consider alternatives.” She agreed.

I first looked at an offer in Cleveland, Ohio. Then the news started to spread that I was considering a move. Before long, I received offers from multiple U.S. cities — eight in all. At the last minute, I got a call from Dr. Arthur Levine, dean of the University of Pittsburgh’s medical school. I was about to sign elsewhere, but Art said, “You are a scientist. You rely on facts. You must visit us before you decide.” So, I went to see Pittsburgh, which turned out to be a delightful place, with a splendid medical school that has a deep focus on science and an exceptional hospital system. I told my wife that we had to consider this opportunity. I had only a few days left to decide, so she went to visit Pittsburgh, together with our daughter and son-in-law, and liked it. She found that the people are genuinely kind and humble. And we liked the Jewish community here, too, and thought that it would be a good place for our grandchildren to grow. We decided to come, and here I am.

At that time, there was no official plan to build the Vision Institute at UPMC, but there was an interest in maintaining a connection with the Institut de la Vision in Paris, which I continued to lead for several years. My job was to get the UPMC Department of Ophthalmology on track to be even better.

When I arrived in Pittsburgh, I spent two months analyzing how the department was delivering care, and proposed a model that I thought would work better. We would build a core facility and integrate clinical care, education and research under one roof. Building a model for access to care for the underserved was also important for me because I was struck, immediately, by the issues facing the locals here who didn’t have access because of poor health-care coverage, or poor education. We had to tackle this dilemma while also developing a model in which innovation was part of what we do. I had done this in Paris, and this is what we have done here.

To build the Vision Institute in Pittsburgh, we received tremendous support from Dr. Arthur Levine and former Chancellor Patrick Gallagher at Pitt, from the Eye and Ear Foundation, and from UPMC leadership. I’m very proud of it because it’s “patient-centric.” It’s about the patient’s experience. It’s about delivering cutting-edge care. It’s about educating the next generation of caregivers and scientists, while educating patients as well to enable them to own their present and future.

In Paris, I started alone but soon worked with 20 teams and 300 people to push us into the next frontier in medicine. This is now happening in Pittsburgh. Since 2023, we have been working in a superb, state-of-the-art facility built by UPMC that brings together caregivers, trainees and scientists to tackle the challenges that affect our patients’ lives. Not all roads will lead to success, of course, and at times we may fail. Persistence is key.

When I was inducted into the College de France, I quoted one of my heroes, the Irish writer Samuel Beckett: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” We must keep trying. And we must fail better all the time. Patients are waiting.