Southwestern Pennsylvania staggered into 2020 in need of people, again. It was coming off of yet another year when deaths outnumbered births and the number of newcomers couldn’t keep pace with the number of residents moving somewhere else.

The COVID-19 pandemic likely makes the already-long odds of a quick rebound in the region’s population even longer. COVID’s grim toll threatens to push natural population losses lower. And cutting the losses by gaining new residents is something that has eluded southwestern Pennsylvania for years and is now more difficult with the migration of Americans from region to region slowing to a crawl.

It is too early to know how the pandemic will influence the direction of the region’s population. But deep-rooted, pre-pandemic trends in aging and migration suggest avoiding further population decline will still be a struggle long after the coronavirus is wrestled into submission.

Costly trend

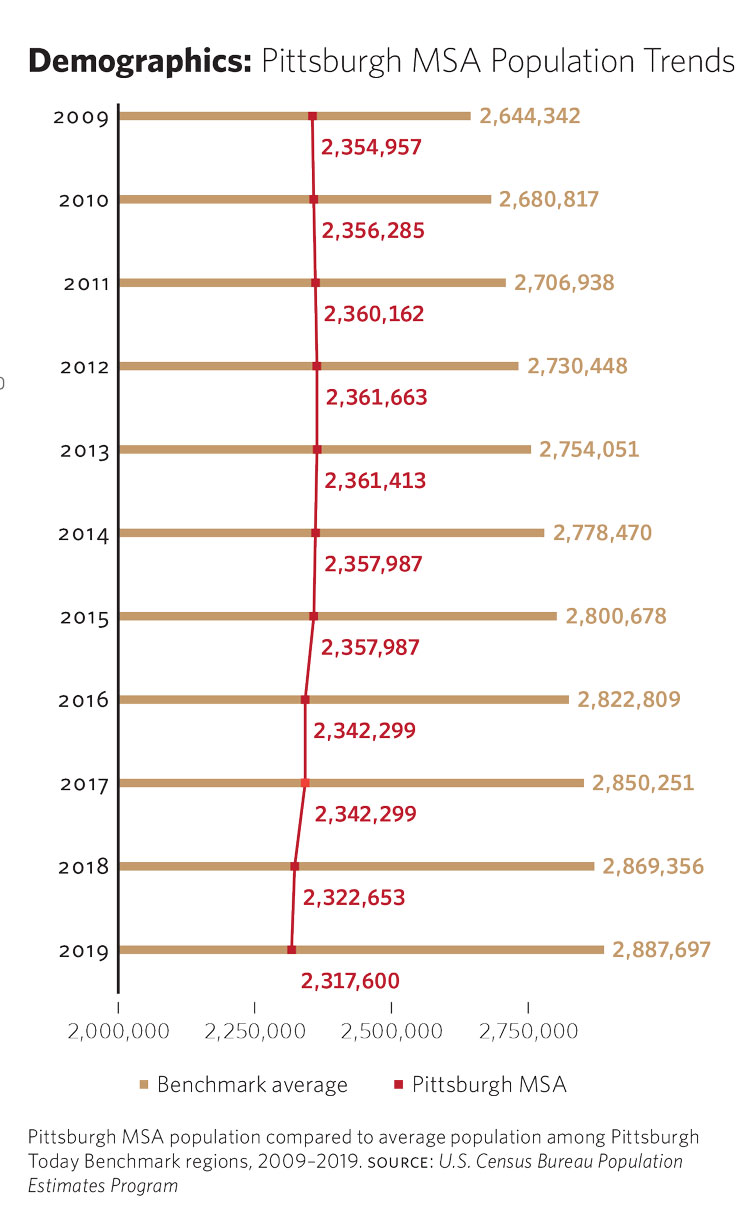

No major U.S. metropolitan area has lost more people and done so more consistently than the seven-county Pittsburgh Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), which has shed more than 400,000 since 1969, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia analysis.

But lately, the region has had company. The U.S. population as a whole hit a wall in 2019, when census estimates show it grew only 0.48 percent from 2018, the lowest rate since 1918, when the nation was at war and dealing with the Spanish flu pandemic. And it’s possible that growth over the past decade could rank as the lowest since the census was first taken in 1790.

In a glimpse of how the pandemic might affect it, U.S. population growth slipped even lower from July 2019 to July 2020, a period that includes three months when the country was in the grip of the virus. “It’s the first time we see a little bit of the pandemic in a year [of census data],” said William Frey, a demographer and senior fellow with the Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program. “Whatever happened before July probably reduced immigration a bit more and increased mortality a bit more. There will be much more of that in the next year.”

Southwestern Pennsylvania’s long familiarity with population loss has been costly, dropping the region from the nation’s 9th most populous metro area to the 27th. And the stakes are high. A regional economy is its people. Population shapes markets for goods and services and the vitality of the workforce. It decides the number of seats in Congress that states are awarded and how many Electoral College votes they wield. It determines the share of federal tax dollars that counties get to pay for health care, schools, transportation and other staples of life Americans count on.

It’s for those reasons and others that economic development organizations and public officials have continued the frustrating search for ways to reverse the region’s chronic population losses for decades. They shouldn’t expect respite anytime soon.

Natural deficit

Southwestern Pennsylvania is still dealing with a demographic phenomenon that has dragged its population lower for longer than a generation. More people die each year than are born in the seven-county Pittsburgh MSA, making it the only U.S. metro area to experience natural population loss.

Having more births than deaths once fueled population growth. But that changed in the 1980s with the collapse of the steel industry that had been the bedrock of the local economy. Nearly 150,000 manufacturing jobs were lost and the exodus that followed cost the region 8 percent of its population from 1980 to 1990. Most of those who left were young people in search of jobs no longer available at home. And with them went their future families, leaving older adults behind and knocking the region’s age structure out of balance.

Decades later, growth in the number of local women of child-bearing age still trails the national rate by a wide margin. Birth rates are below the national average. The share of the population claimed by residents 65 years and older is one of the highest in the nation, as is the number of deaths per 1,000 residents, census data suggest.

COVID’s toll threatens to temporarily increase the region’s natural population losses. The virus claimed the lives of nearly 3,000 people in the Pittsburgh MSA during the first 10 months of the pandemic. The hope that the pandemic, by forcing couples to spend more time at home, will lead to more births is tempered by evidence that past recessions haven’t had that result.

And it will take a lot to derail the trends driven by the region’s aging population. “Even if those shift a little bit, the demographics of the region are pretty much baked in,” said Chris Briem, a regional economist at the University of Pittsburgh’s University Center for Social and Urban Research. “The range of potential outcomes is pretty narrow.”

Stuck in place

The flow of people from one region to another hasn’t worked out well for southwestern Pennsylvania, and it doesn’t appear that will change soon.

For only one brief moment this century has southwestern Pennsylvania attracted more people than it lost—a five-year span that Briem found was driven by the boom in Marcellus Shale natural gas production some 12 years ago. When those jobs slowed, the migration gains disappeared.

Whether the COVID-19 pandemic can somehow steer more people to the region remains to be seen. Most people move between regions for job opportunities. But the Pittsburgh metro area’s labor force was shrinking more severely than in the nation as a whole by the end of the year. Jobs were being restored at a more sluggish pace. And PNC Financial economists expect the region’s economy to recover more slowly than what will be seen across the nation.

The virus and the social and business restrictions taken to slow its spread have broadly damaged local economies and jobs throughout the nation. For people in job sectors hardest hit during the pandemic, there are few opportunities for work anywhere, dampening the incentive to move.

“In the 1980s, we had job destruction far in excess of what was going on in other regions. It just made sense for some people to pick up and move,” Briem said. “The difference now is that if you’re a waiter or hotel worker, those opportunities are being destroyed everywhere. There isn’t one region that has survived this well.”

Americans weren’t doing much moving to begin with. U.S. migration fell to a 73-year low right before the pandemic, when only 9.3 percent of Americans moved between March 2019 and March 2020, census data show. By comparison, the decade following World War II saw about 20 percent of the population move during a year.

The slowdown is seen in all age groups. But the migration of young adults declined the most in the decade before the pandemic. And some large metropolitan areas that had experienced robust population growth early in the decade were the biggest losers by the end, as what little migration there was began to favor smaller places.

No U.S. metro area lost more residents from 2012–15 than Pittsburgh, Frey’s analysis of U.S. Census Bureau population estimates shows. Although the region’s population continued to slip, it relinquished that unwanted crown by the end of the decade, when New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Cleveland posted larger losses.

The wild card in the pandemic is the surge of people doing their work remotely, which began when offices, schools and other workplaces closed or reduced occupancy to contain the outbreak. Nearly one-third of small and medium-sized businesses in southwestern Pennsylvania adopted work-from-home policies last year, a PNC Financial Services survey found.

It’s unclear how broadly remote working will be offered after the pandemic and whether workers given the opportunity will follow longstanding migratory patterns or break from them. “Most people move to places that are close by or larger,” Briem said. “You don’t see many people moving from San Francisco to Pittsburgh, as much as some people think that happens.”

Help from abroad

While migration from other parts of the country has failed to boost southwestern Pennsylvania’s population, immigration has consistently added to it. Still, less than 4 percent of the region’s population is foreign born, one of the lowest rates among U.S. metro areas.

Their impact is most greatly felt in the region’s urban core. Nearly 80 percent of the region’s foreign-born residents live in Allegheny County or the City of Pittsburgh. They’re particularly important to local universities, where they contribute to enrollment and the bottom line. As Briem said, “The flow of international students is a non-trivial part of population here.”

And immigrants tend to bring more than themselves to the table. “Immigration impacts the age structure,” Frey said. “Immigrants and their children are younger than the population as a whole. One way to buck up your younger population is immigration. They’ll come here and have children.”

But prospects for increasing the flow of immigrants to the region face strong headwinds at the moment. The pandemic led to travel restrictions and to colleges closing or going remote—circumstances that are expected to send immigration even lower.

More restrictive U.S. immigration policy in recent years had already sharply reduced the number of people from other countries who settle in America. Frey pointed out that the nation barely added 200,000 people to its foreign-born population in 2018 and 2019. Earlier in the decade, the nation’s foreign-born population had been growing by 400,000 to 1 million people a year.

As a result, immigration gains over the past decade are expected to be the lowest since 1970, despite coming during a period of economic expansion, when jobs are more plentiful. “We have to be serious and think about what level of immigration we should have in the United States and how it can help us be a more productive country,” Frey said. “If we don’t, we are going to have a continually aging population. In 10 years, most of the baby boomers will be retired and we’re going to have to count on a smaller younger generation to keep things going.”