Southwestern Pennsylvania and air quality have long had a complicated relationship. For the better part of a century, the region had been a place so polluted from the soot of industry and homes heated by coal that street lamps were lit in the afternoon and walking a single block could ruin the collar of a white dress shirt. Pittsburgh earned the enduring image as the “smoky city.” And Donora in Washington County experienced the nation’s worst air pollution disaster.

But Pittsburgh also stands as one of the pioneers in regulating pollution sources. And the work of researchers in the region has advanced the understanding of the health and economic toll that air pollution exacts and has influenced national environmental policy.

Today, the region’s air quality is markedly better than when steel and other heavy industries were in full bloom. Yet, better is not good enough to meet federal limits on some of the most widespread pollutants, posing risks to the health of people residing in hundreds of zip codes.

In 2015, Pittsburgh announced that future city development would be guided by the principles of sustainability, including stewardship of its air quality. The same year, the governors of three states unveiled a plan to promote a region that includes southwestern Pennsylvania as a chemical manufacturing hub fed by abundant natural gas extracted from local shale and led by a multibillion-dollar ethane “cracker” petrochemical complex under construction in Beaver County.

This is the introduction to a series of articles that will examine air quality in southwestern Pennsylvania, from where we are today in the struggle to tame air pollution to how we got here and where the region is heading—an evolution that has been, and likely will continue to be, anything but simple.

Valleys and inversions

Southwestern Pennsylvania has faced a daunting challenge to clean its air for more than a century. For starters, its rolling topography, weather and prevailing winds make it more susceptible to concentrated air pollution than most other U.S. regions.

Steelmakers were immediately attracted to the region’s river valleys, which offered convenient water transportation to feed their mills with raw materials and move finished product. But the advantages the Ohio, Allegheny and Monongahela rivers offered the mills that came to occupy their banks came with a high price to the environment.

The region’s hills and valleys prevent airborne pollutants from being uniformly distributed, with the valleys generally holding higher concentrations for longer periods of time. Such “hot spots” or pockets of dense pollution characterize the region.

To make matters worse, the region’s river valleys frequently experience temperature inversions—100 days a year on average— when air that normally becomes cooler as it rises becomes warmer instead. A pocket of warm air above cooler air acts like a lid, preventing vertical mixing and trapping the cooler air and any pollutants it contains near the earth’s surface.

The most infamous of these events occurred in October 1948, when an inversion clamped down on the town of Donora along the Monongahela River for four days, trapping soot and gases from its steel, wire and zinc works. Thousands were sickened and 20 people died, thrusting the town into the international spotlight and raising awareness of the health risks of pollution. One year later, Pennsylvania established the Division of Air Pollution Control to study ways to improve air quality. Six years after that, the state’s first air pollution control standards became law.

Another critical weather factor in the region is the prevailing winds, which arrive from the west and southwest. That puts southwestern Pennsylvania in a steady current of air pollutants from Ohio River Valley and Midwest power plants, industries and motor vehicles in upwind cities. Airborne particulates travel the winds particularly well and are capable of covering hundreds of miles before being flushed out by rain.

Smoke clears

As bad as the region’s air was when steel was booming, corporate leaders and millworkers alike regarded industrial emissions as the smell of money. And when ridding the region of the ever-present blanket of smoke became a target for civic improvement following World War II, the industries that produced much of the air pollution were largely given a pass.

Pittsburgh’s Smoke Control Ordinance adopted in 1946 as part of a broad urban renewal plan is the region’s best-known environmental achievement. The popular account credits Mayor David L. Lawrence and business and community leaders with wrangling into law a smoke abatement strategy that cleared away much of the heavy soot in short order and helped launch the city’s first renaissance. Not mentioned are the German U-boats that played a key role in the success of the ordinance.

Lawrence and colleagues believed the ordinance would compel homeowners, businesses and industry to shift from bituminous coal for heating to a processed coal called Disco that created less soot. But it proved to be expensive and prone to shortages.

Instead, it was the transition from coal to natural gas home heating that relieved the city of its smoke problem. And the pipelines that made Texas natural gas available to Pittsburghers had been built by the federal government as a secure, interior oil transport route during World War II when German submarines hunting in Gulf Coast waters were sinking tankers and threatening oil shipments to northeastern states. No longer needed for oil after the war, the pipelines found new life transporting natural gas.

Pittsburgh converted to natural gas faster than any city in the nation, and three years after the city began enforcing its Smoke Control Ordinance, only 32 percent of homes burned coal for heat compared to 81 percent a decade earlier. The impact was dramatic. Smoke had reduced visibility eight hours a day in 1949. By 1958, it was a problem only for one hour every three days.

Allegheny County, home to a large share of the region’s steel mills, followed with its own anti-pollution rules. Both city and county ordinances were drafted with considerable input from the industries most affected by them and it showed. The first set of county regulations, for example, only required coke ovens and open-hearth furnaces at steel mills to adopt pollution controls that were “proven to be economically practical.”

And while concentrations of coarse airborne particulates that appear as smoke fell dramatically, the ordinances failed to address largely invisible fine particulates and gases from industrial sources and motor vehicles, which remain the region’s most stubborn air quality problem.

Federal regulations for fine particulates known as PM2.5 didn’t go into effect until 1997 after scientific evidence convincingly demonstrated its potential to harm. Its microscopic size enables PM2.5 to slip past the hairs and mucous membranes in the nasal passage and other natural defenses and make its way deep into the lung and blood stream, making it particularly dangerous to human health.

Bluer skies, lingering risk

In 2013, nearly two-thirds of southwestern Pennsylvania adults described the region’s air quality as either a minor problem or not a problem at all when interviewed for the Pittsburgh Regional Environmental Survey conducted by Pittsburgh Today and the University of Pittsburgh’s University Center for Social and Urban Research. Only 5 percent saw it as a severe problem.

That year, the region violated Clean Air Act standards for the two major air pollutants that spread hundreds of miles: ground-level ozone and PM2.5. One likely reason for the public misconception is that both are barely visible even in high concentrations.

Both were in abundance in the late 1960s when Lester Lave, an economics professor at Carnegie Mellon, and colleague Eugene Seskin began comparing county air pollution data and health records using the tools of applied economics to determine the correlation between the two. They confirmed what many suspected: People in places with the worst air pollution had the highest risk of dying prematurely. They were also able to calculate the financial loss, reporting that pollution- related illness, lost workdays and early death cost billions of dollars each year.

More important, their methodology withstood scientific scrutiny and opposition from industry to inform major federal regulations to improve air quality, as well as hundreds of subsequent studies that further identified and defined the health risks of a wide range of air pollutants.

The most impactful of those laws was the federal Clean Air Act of 1970. The act and subsequent updates have created and refined air quality standards for an expansive list of air pollutants based chiefly on the risks they pose to human health.

Among them are six “criteria” pollutants commonly found in the United States: ground-level ozone, PM2.5, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide and lead. Levels of each must fall within prescribed limits for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to consider counties and regions to be in attainment of the standards, which can be ratcheted tighter if more evidence of their harmful effects surfaces.

Also regulated are 187 hazardous air pollutants, also known as air toxics, about half of which are known carcinogens, such as benzene, which is widely used in industry and found in motor vehicle exhaust. Air toxics are less widespread than the criteria pollutants, but high concentrations and prolonged exposure can cause harm. Many air toxics are also precursors for atmospheric ozone formation or are involved in the formation of harmful air particulates.

Compliance and enforcement largely falls to the state Department of Environmental Protection in six of the seven Pittsburgh MSA counties. The exception is Allegheny County, where some of the largest pollution sources in the region reside. The EPA gives those duties to the county health department, which deploys inspectors, records air data across a network of monitors, writes rules for reducing emissions, fines violators and orders corrective actions making Allegheny one of most closely regulated counties in the nation.

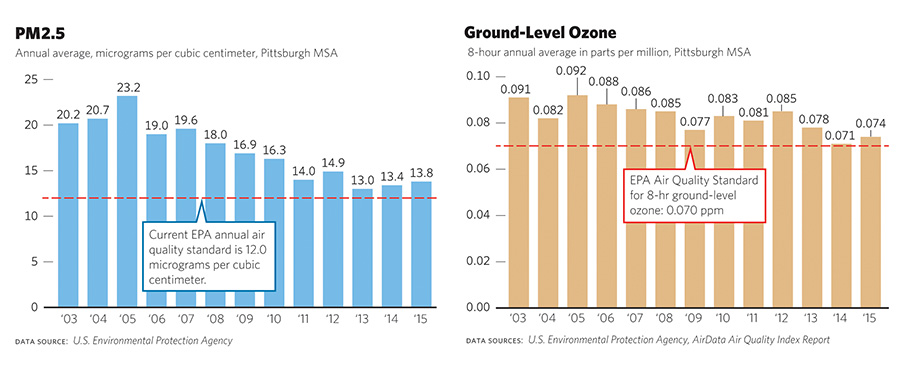

More stringent regulations are among the reasons pollution levels in southwestern Pennsylvania have steadily, and in some cases, dramatically fallen over the past three decades, including ozone and PM2.5. Persistent advocacy for cleaner air is another. Technological advances and industry investment in reducing emissions have also contributed.

Economic factors also have played an important role, particularly the decline of the steel and related industries that razed many of the largest single-source emitters of pollution at the cost of tens of thousands of jobs. The most recent was the Shenango, Inc. plant on Neville Island in the Ohio River five miles downstream of Downtown Pittsburgh. It was closed early in 2016 by its parent company, Michigan-based DTE Energy Services, citing flagging demand for the metallurgical coke it produced. A year earlier, Shenango had agreed to a consent decree that included a fine and repairs to correct problems that led to 330 air pollution violations over a 14-month period.

But better air is not necessarily good air when evidence that links pollutants to disease, disability and premature death is considered. Exposure standards, once considered adequate to protect human health, have from time to time been rendered obsolete by new evidence of a pollutant’s potential to harm and made more stringent. For example, the eight-hour annual standard for acceptable ground-level ozone pollution was lowered from .075 parts per million in 2008 to .07 in 2015. And PM2.5 was tightened from the 2006 standard of 15 micrograms per cubic meter of air to 12.

Today, counties in the Pittsburgh MSA are in nonattainment of federal standards for four of the six criteria air pollutants, despite the fact that levels of each have fallen significantly during this century.

All seven MSA counties, similarly to many metro regions in the Northeast, continue to be in nonattainment of the annual limits for ground-level ozone, a gas formed by a reaction of sunlight and the vapors emitted when fuel is burned by cars, buses, trucks, factories and other sources. Ozone travels hundreds of miles and can harm lung tissue, reduce lung function and worsen bronchitis, emphysema and asthma.

Beaver County is in nonattainment of the standard for lead air pollution, a pollutant to which infants and children are particularly sensitive and which studies warn threatens the nervous, immune and other vital systems, as well as the heart, kidneys and children’s development.

Beaver joins Allegheny and Butler counties in failing to meet the standard for sulfur dioxide, which can harm the respiratory system and react with other compounds to form PM2.5.

Allegheny County is also one of only 20 U.S. counties that have failed to achieve attainment of the standard for PM2.5, which scientific evidence suggests increases the risk of respiratory ailments, premature death, stroke, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Back to the future

Momentum has been building in southwestern Pennsylvania for longer than a decade around the strategy of guiding the region’s future development along the principles of sustainability, which include promoting a healthy environment, and make clean air a priority. Nowhere is there more interest in such an approach than in the City of Pittsburgh.

Greening the built environment began to rise more than a decade ago in the city, which today holds more than 160 U.S. Green Building Council LEED-certified buildings. In 2008, the city adopted a Climate Action Plan with strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In the city’s Oakland and Downtown neighborhoods, owners and managers of 270 buildings embraced a challenge to cut their energy consumption in half and already have reduced it by 12.5 percent.

Where a steel and coke works once stood in the city’s Hazelwood neighborhood, philanthropic dollars are financing a mixed-use community built to sustainability principles that forbid the poor air quality and other environmental insults its former tenant had imposed.

Nearly two years ago, Pittsburgh Mayor William Peduto launched an initiative to recast the city as a model of urban sustainability that includes environmental impact as a chief consideration in future development. It includes performance measures against which projects competing for subsidies and other public incentives will be judged, including how they affect air quality.

Meanwhile, abundant fossil fuels are restoring the region’s allure to industry. Unconventional natural gas drilling expanded significantly during much of the past decade, although production has slowed with falling gas and oil prices. The expansion has occurred with little understanding of the impact on air quality and public health, both of which remain under-studied.

The gas-rich shale inspired the governors of Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia to collaborate on creating conditions attractive to petrochemical companies that rely on natural gas byproducts as feedstock. And last year, Shell broke ground on an ethane cracker complex on a site in Monaca, Beaver County, where a zinc smelter had operated. Preparing the site and the construction of the plant is expected to create thousands of jobs that will give way to 600 longterm jobs in counties where such jobs are needed. A cracker takes ethane produced during natural gas extraction and breaks apart the molecules to make ethylene used in plastics manufacturing.

Such a plant could significantly alter the local air pollution mix, a University of Pittsburgh study suggests. To assess the risk, researchers compared air quality data from a cracker plant operating in Louisiana to air data from the zinc smelter which the Monaca cracker replaces. They found the Monaca cracker would likely emit lower levels of heavy metals, including lead, than were released from the zinc smelter, as well as lower levels of criteria pollutants such as PM2.5. But they warned that the new plant could also lead to greater releases of known carcinogens, such as formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, and higher cancer risk in nearby communities.

Forecasting what the future holds also is complicated by uncertainty surrounding the federal regulatory climate under the administration of President Donald Trump. Federal rules can greatly affect local air quality as demonstrated by the improvement in the region’s air under Clean Air Act regulations in recent decades.

What is clear is that the tension between environmental and economic concerns will continue to influence air quality in southwestern Pennsylvania as it has for more than a century.