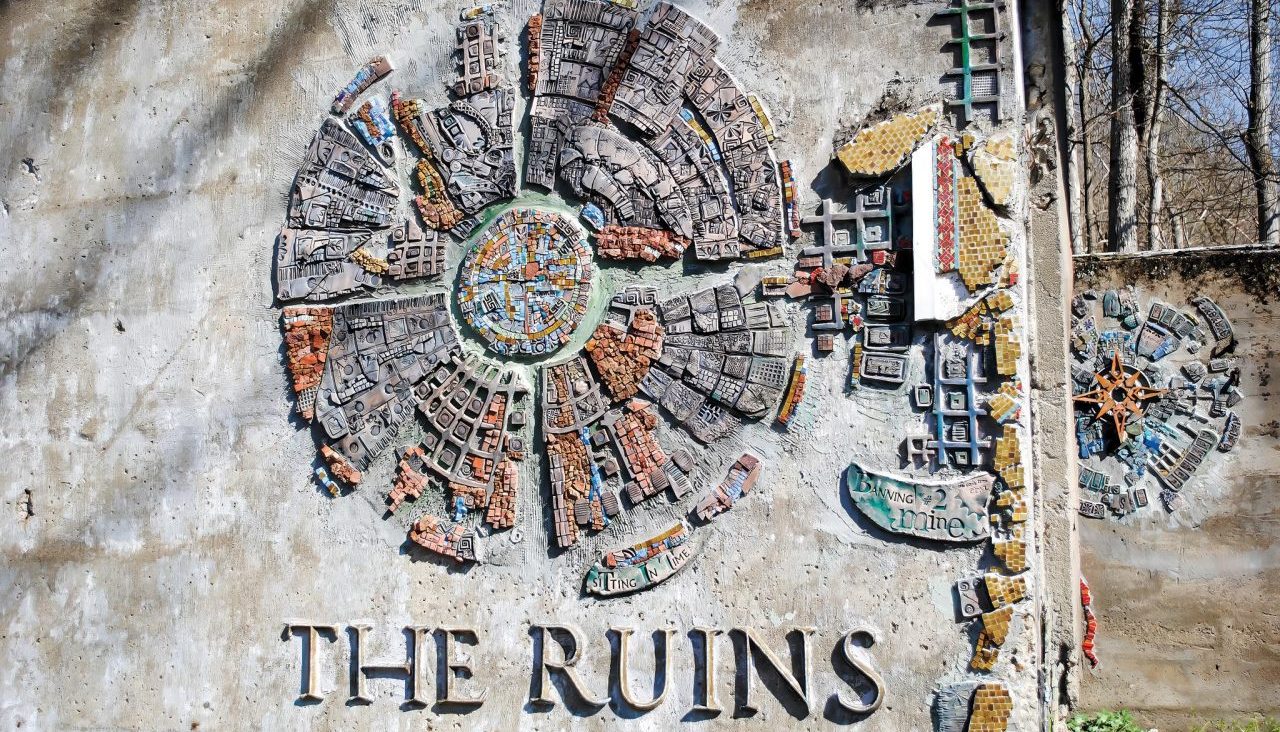

The Ruins

When Rachel Sager bought a house, she didn’t know it came with a coal mine. Obscured by woods in her “backyard,” and flanking the Great Allegheny Passage (GAP) bike trail, are the sprawling ruins of the once robust Banning No. 2 coal mine: a labyrinth of crumbling brick and weathered concrete, wedged between bluffs and the Youghiogheny River’s floodplain at Whitsett, Fayette County. The house she bought was once the mine’s office.

“I’d known about this house my whole life and was entranced by it, and I was strongly attracted to the bike trail,” Sager said. “I’d been living in Pittsburgh and doing mosaic art, looking for space to branch out. The house was rundown, but I bought the place in 2015 when there was a blanket of snow over everything. When the snow melted, I walked around the maze of buildings with a cup of coffee wondering, ‘What did I do?’”

Soon, Sager’s bewilderment transformed into a way forward, one that could serve both her art and her reverence for mining history.

“I’d been feeling a kind of angst because I was growing as an artist, but also wanted to somehow honor coal mining and what it meant in the lives of miners and their families,” Sager reflected. “Those two drives within me had no common ground until I looked across these bare walls of concrete and brick — a perfect stage for mosaic.”

Sager was surprised that no graffiti marred the walls. “For something around this region, abandoned so long, that’s unusual.”

Mosaic is an ancient art form dating back 5,000 years to Mesopotamia, and later refined during the successive peaks of the Roman and Moorish empires. A mosaic is a picture or design made from small pieces of stone, glass, mineral, shell, or tile of various colors. Artists affix the prepared pieces to a surface — walls and floors were frequent receptors of mosaic in ancient Rome and in Moorish mosques — with mortar or plaster to complete the image they’d conceived.

Sager began placing mosaics that celebrate mining history on the ruins’ walls. “This would never have happened if I weren’t from a coal family,” she said. “Once you’ve been part of that, it’s impossible to forget the pride miners around here took in their work.”

But Sager’s worldview is broad, and her compulsion to relate story through art went beyond coal mining heritage. She began thinking of the project as a medium for different threads of story that interpret the intertwined themes of industry, culture, and nature, so entrenched in the Youghiogheny Valley and throughout southwestern Pennsylvania’s history.

“I knew people in the mosaic community who could do things I could never do, and I had these walls and an audience along the bike trail. I found myself here in a perfect storm for mosaic,” Sager said.

Since 2015, she has invited more than 250 mosaic artists from all over the United States and from Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, England, India, Israel, and Scotland to Fayette County to place art on the mine walls of Whitsett.

She titled the project “The Ruins,” which continues to grow and spread on surfaces throughout the buildings’ remains. Mosaics of astounding color and variety now grace the walls of the Banning No. 2 ruins, transforming neglect into an “ecology,” as Sager puts it, of art, industry, and nature.

A prominent compass rose, made from scrap steel, scavenged on-site, greets visitors as they enter the complex. The compass rose, Sager explains, orients you to the Earth, which is important. On a broad wall next to the rose, narrow bands of parallel red and blue tiles wind, serpent-like, from the wall’s lower-right to its upper-left corner, tending southeast-to-northwest by the compass rose. The arcs of brilliant color portray the Great Allegheny Passage from its entry into Pennsylvania near Confluence to Pittsburgh, flanking the Youghiogheny River most of the way. Red represents the trail and blue, the river.

Sager sees the GAP as a sign of the region’s awakening to its astounding natural beauty, and the trail mosaic ushers visitors into the ruins with an image to which they can easily relate.

“People on the trail are happy, positive people,” she said. “They’re on a different kind of highway, looking for something compelling and beautiful, and that’s everywhere along this path.”

Around a corner, visitors behold one of The Ruins’ most elaborate works, crafted across a wall that was part of the mine’s “fan house.” When the mine was active, the fan house enclosed an immense motor-and-belt assembly that forced breathable air underground.

“This is the Patch House Project,” Sager says quietly. “It’s a collaboration of 32 artists and took a year to plan.”

The term “patch” may be unfamiliar to regional transplants or younger area residents. “Patch” was a highly local term for the housing plans companies built near their mines, or coal patches, for workers. Companies deducted rent from a miner’s pay. All patch houses were identical and faced the streets and alleys in the same orientation. Most housed two families, one to each divided side. A more widely recognized term for such a community is “company town,” but “patch” is endemic to southwestern Pennsylvania, especially Fayette and Westmoreland counties. Whitsett was such a patch when its mine was active, its rows of houses wedged between the Youghiogheny and the bluffs. Today, Whitsett’s residents own their homes.

From the floor to about visitors’ eye-level stand three rectangular mosaic panels. Each is a grid of different “patch houses,” pieced together with native stone, smalti (small cubes of cut glass), or ceramic. The three panels exhibit 175 different patch house interpretations, some with intricate family scenes visible through windows. In one window, a woman wearing a “babushka” shares a basket of grapes, picked from her family’s modest arbor, with a neighbor. Viewers might imagine the grapes becoming wine for Christmas sharing.

After initial awe, a viewer senses the grids of houses also represent quilts, like those made by miners’ wives.

“This honors family life in the patch,” Sager said. “It’s symbolic to use the quilt concept, as it is such a domestic art form. The quilts, displaying patch houses, celebrate the women and children in miners’ lives, the other side of a threshold a miner crossed every day.

“When this mine closed,” Sager continued, “much of that energy and community of ‘patch life’ left here, dispersed elsewhere.”

Poignantly, the artists did one of the Patch House panels in what Sager termed “Picassiette,” a mosaic form using scraps of tableware. The artists salvaged broken cups and dishes from abandoned patch houses around the region.

“A lot of math goes into a piece like this,” she observed. “People don’t link art with mathematics, but you can’t begin such an intricate mosaic without precise measurements and calculations.”

To Sager, the mine walls are more than mere backdrop. “This piece of industrial architecture is vital to the story. It’s not just a canvas to display our art,” she said. “Banning No. 2 was called ‘The Million Dollar Mine’ because it was one of the most productive mines in the Youghiogheny Valley.”

Banning No. 2 operated from 1893 to 1946, as part of the Pittsburgh Coal Company’s dense network of mines within a swath of Fayette and Westmoreland counties known as the Connellsville Coke Region. Though its heart spanned only about 10 miles east-west, and 35 miles north-south, the Coke Region boomed in the early 20th century. The subterranean tilt of the 10-foot-thick Pittsburgh bituminous coal seam, the highest-quality metallurgical coal in the world, cropped out at the surface, accessible to the pick, shovel, and horse mining technology of the day. Most of the millions of tons of coal mined at Banning No. 2 and throughout the Coke Region were baked into coke in 40,000 coke ovens that lit the night sky orange, then were shipped north by train as fuel for Pittsburgh’s steel mills.

Several mosaics pay tribute to miners. Arizona artist Donna Van Hooser’s startlingly lifelike image shows Rachel Sager’s father, Jeffrey Luce Sager, smiling as a young man, the sleeves of his work shirt rolled up in preparation for a shift.

William Henry Mills stands at full height, lunchbucket under his left arm. “Joy Parker, from Scotland, did this piece to document that black miners made up a large part of Banning No. 2’s workforce,” Sager said. “And Whitsett is still a 50-50, black and white community in rural Pennsylvania, because of this mine.”

Nearby, Victor Kulengosky’s (1912-1966) likeness is crafted from tiny glass beads, different tints incarnating the face’s strong contours. But Victor’s eyes are different, larger glass fragments shining out, lifelike and probing.

Two harnessed workhorses flank John Moskal’s image, enshrined by Florida artist Gila Rayberg as “Master of Horse,” an esteemed skill before mechanical power replaced horses in the mines.

One portrait wears a miner’s cap and headlamp, his face calm, resigned to hard work in darkness but revealing no hints of ethnicity or race. “This is ‘The Anonymous Miner,’” Sager says. “He represents the ones we will never get to with mosaic portraits.”

The three-dimensional “War Horse” stands atop a ledge, made from wedges of broken pottery, seeming in conflict with one another. The horse is poised for work but gazes toward a square of bright blue-and-white mosaic.

“Helen Nock, from Scotland, used a war horse as a metaphor for men going into battle in the mine,” Sager explained. “The blue panel represents sky and fresh air. It’s a bittersweet image, knowing that a coal horse spent so much of its life underground, without the sky.”

A different kind of horsepower dominates a long concrete wall that parallels the GAP and the river. There, Pittsburgh artist Stevo Sadvary melded thousands of pieces of Youghiogheny glass into “The Great Train,” a Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad locomotive, tender, coal car, and caboose. The train is 70 feet long and seven feet high, but with artful interruptions.

“The train deliberately doesn’t cover the whole wall,” Sager said. “Stevo left bare strips of concrete to represent trees, and Jan Dongilli later shaded the strips of bare wall to give the trunks texture.”

Where “PITTSBUR H & LAKE ERIE” is spelled out across the tender, one “tree” blocks the “G” in Pittsburgh from view, injecting a sense of space. “The tree blends the work with the surrounding woods,” Sager said.

Through the heyday of the coke industry, the train depicted at The Ruins was hailed as “Little Giant” because the tonnage it carried hauling coal from mines to coke ovens around Connellsville, then back to Pittsburgh mills loaded with coke, was disproportionately large for its short 100-mile round-trip.

“The train is still headed toward Connellsville,” Sager beamed. “Hauling coal to the ovens.”

Sager pointed out that a family-owned firm in Connellsville still makes the Youghiogheny glass that brings the Great Train to life. “We’re proud to use this high-quality local product. Our artists love working with it,” she said.

Easy to miss is a tiny black-capped chickadee incongruously, but perhaps whimsically, riding atop the locomotive’s headlight.

“In the same way The Ruins recalls industrial history, we’re also recognizing nature. The chickadee on the train articulates that,” Sager said. “The ecology of this place underwent immense change, and it’s changing still today. All the ash trees have died, but bald eagles are back on the river.”

Sager asked various artists to recreate, in mosaic, the native birds of Pennsylvania. She calls it “The Feather Project.”

Perched among images of mining and machines, elegant birds delight the eye. A red-crested pileated woodpecker tenses, ready to flush from a tree, and an American kestrel flashes orange feet tipped by black talons. A belted kingfisher appears to doze on its perch, but also looks coiled to dive for a fish. Almost too real to be made from blue and brown smalti, a barn swallow swoops across brick, and a white-breasted nuthatch flutters its wings atop the rustically displayed words “Fayette County.” A wild turkey gobbler, its feathers fashioned from slate, broken plates, and smalti, struts in mating display. Honored even in its extinction, a passenger pigeon eyes visitors from its high place of regard.

“There was a time when I thought [The Ruins] was almost finished,” Sager reflected. “But I’ve left that behind. There are more ways to keep telling this story. Maybe I realized how important this has become to other people, like the wife who came here to have her photo taken next to the mosaic of her dead husband.”

That mosaic shows three young boys from Whitsett, before they went into the mine, arms linked in a happy break from play beside a coal train.

“The Ruins isn’t for everybody,” Sager continued. “It’s for people who can slow down and think about time and place, about change and constants, but it all arcs back to the coal miner. I want this work to be something visitors can learn from, and that people from here can be proud of.”

Walking quietly among The Ruins’ brooding walls, that pride which Sager strives to evoke wells up, lingering long after.