The Man Who Took Away Snakes

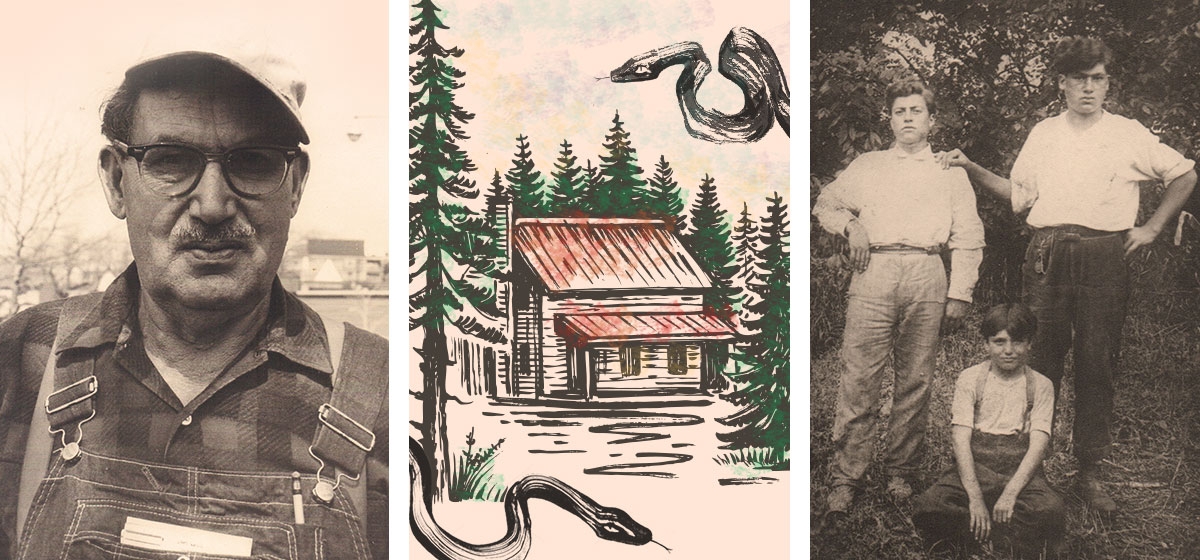

No, he wasn’t always a plumber for the City of Pittsburgh, and he wasn’t always called Pupi either. His wife called him Andy. Pupi told me this story one day when we were hunting at “The Farm.” I was his hunting dog that day. My job was to kick brush piles so that rabbits jumped out. Pupi said you should always shoot rabbits in the head. You don’t want to be picking BBs out of the meat. He was from an era where if you shot it, you ate it.

His parents brought him from Calabria when he was a child. Andy was tall for a Southern Italian—five foot nine, dark-haired, and dark-skinned, like most Southern Italians. With his broad shoulders, he could really swing a sledgehammer. So he worked in a rock quarry. They drilled holes in the rock, filled them with dynamite, and blasted open a fractured rock seam. Then they chiseled the rock off the seam. One day, working with a partner, his hammer hit the chisel next to a dynamite-filled hole. The blast let loose unimaginable force, like the mighty breath of God. It blinded Andy. Dominic lost a hand.

His conscience tortured him daily. A man’s duty was to support his family. In his mid-20s he had married Victoria, and they lived on Pasture Street in the Hill District where he grew up. It must have killed him—sitting around Pasture Street blind, smelling the comforting aroma of garlic and sauce on the stove, mixed with the sharp sulphur reek of the steel mills. His father’s brother, Mike, clunked around the kitchen and left for work. John and Sam carped at each other waiting for the shower, “Make it snappy! Save me some hot water for a change!” Victoria, now pregnant, did housework. Andy heard his parents’ worried voices murmuring in Italian. His mother prayed to La Madonna, her fingers rapidly working her rosary beads.

Later when his sight came back, he worked around the city. At first, Andy tended the horses and donkeys riding the incline for the animals. He later hitched them to the work wagons atop Mt. Washington. Andy’s voice quieted them. When the donkey acted up, he swatted its rump and told him to behave, “Basta, rigo dritto.”

Eventually, a plumber named Johns hired him. Andy at first was a laborer, digging ditches and doing pipe work. When the shop went union, everybody had to be union. The laborers were lucky. It wasn’t easy to get into the union. Years later, Andy made sure two of his sons got into the Plumbers union.

But Victoria would never have sons. She died giving birth to the baby they named Rose. He couldn’t bear to think of another woman until Rose was 6-years old. Andy married Frances Iuni, Neapolitan but American-born. Her family, they didn’t like it. This older man, this Andrew Bianco, with a child to take care of and a house full of relatives. They told 16-year-old Frances he wanted a maid to take care of the baby and his relatives. She married him anyway. Her parents and the gang of loud Iuni sisters didn’t attend the wedding. Andy and Frances had three sons, Anthony, John, and Michael, followed by a daughter, Anna.

The sons grew up on the streets of the Hill District. But one son knew the streets too well—up and down Wylie Avenue all the time, getting in with the wrong crowd. That’s my dad John the cocky one, who else? Andy finally had to strong arm him into the plumbers apprentice program. One day he had enough, and angrily took his son by the shoulders out to the alley, the buildings around them covered by soot, “Giovani, what you do, running numbers and who knows what, you don’t build a life. You gonna raise a family that way? Madonna mi. You won’t get anywhere but dead hanging around those bad men.” His soft voice rose in volume. “You better turn your life good, make up your mind.” So two sons became plumbers’ apprentices, while the other became an electrician.

When the city started tearing down their neighborhood to build the Civic Arena, they had to move. Frances heard other Italian women talk about Dormont, a nice place south of the city. In Pittsburgh, you worked to get out of the city. You were poor if you lived somewhere like the Hill District, closer to the soot and sulphur stink of the mills.

They found a house in a quiet Dormont neighborhood. Solid, old trees lined the street. A wide, meticulous brick house had no soot film like those in the Hill District. It had a broad, generous brick front porch. Inside, the high-ceilinged rooms shone with beautiful mahogany woodwork in ceiling beams and staircases. The large dining room had built-in mahogany cabinets. This house radiated old-fashioned, peaceful grace.

So the first night the family moved in, some guys from the Dormont football team showed up. Dad burst out the front door with his brothers. They strode out to the grass to confront these chadrools on their lawn. Before anyone knew it, somebody punched somebody. In the end, they gave those Dormont boys what for, as Andy came out of the house with his gun, and the police showed up, sirens screaming.

Andy started hunting in the 1930s because his brother Jack was a big-time hunter. Soon the brothers and cousins started. In 1957 they pooled their money and bought a piece of land from a farmer 5 miles west of Imperial, in Findley County. They called it “The Farm” and hunted small game there. Fifteen founding members formed a club and each had a share. Later on, they heard of a simple cabin for sale in Tionesta, Forest County, near the Allegheny National Forest. The place needed a lot of work, but they were already driving up there every year.

A tradition started in that cabin that continues to this day. On Thanksgiving weekends, we all left for Tionesta for the start of deer hunting season, with food cooked by all my aunts. The members and their relatives came: my dad John, and me, Pupi (by then it was what his grandchildren called him), Uncle Steve the painter, Uncle Tony, Uncle Mike and their sons Andrew and Mikey, and Uncle Carnie. His son Carmen arrived. I was 11-years-old the first time I went, not even legal to hunt.

So we’re all sitting around the table. Uncle Mike brought pop for the kids. Carmen heated everything and poured sauce over the stuffed shells my mom made. Uncle Tony made a salad and cut the hard-crusted Italian bread. “Mangia, mangia,” Uncle Mike declared. Around the table came olives, bowls of Italian peppers, creamy ricotta-stuffed shells, and the Italian greens Uncle Mike made. A string-tied roll of beef braciola covered in sauce followed. It was cut in slices with hard-boiled eggs in the middle. Cousin Carmen looked at me and asked, “Did you know your grandfather was charmed by a snake?” My eyes grew wide. The men constantly told me stories to see what I might believe so they could laugh at me. Cousins Andrew and Mikey looked up.

I studied Pupi. “You were, for real?” I asked, “How do you know?”

Uncle Mike rolled his eyes at Tony.

Pupi looked at them sternly. “Giovani and the boys never heard this story,” he said.

Pupi sat back and adjusted his chair. “When I was a baby we lived in one of those grass shacks, made out of grass, young shoots.” He gestured with his right hand.

Dad asked, “Where in Italy were you born, the town?”

Pupi answered, “Sersale, near the state of Catanzaro. I was born in Sersale in 1896.”

“And when you were charmed by the snake, how old do you think you were?” dad continued.

“I was a baby,” Pupi stated emphatically, “I wasn’t a year old because I’d fall out of the bed. So they made me a bed on the floor.”

“So what happened Andy?” Cousin Carmen asked.

Pupi continued, “This snake, nobody knew him. This snake used to come out at night and drink milk from the buckets, you know. This snake she’s been doin’ it right along. My father —who by the way was your grandpa, your nonno, he said while looking pointedly at my dad and uncles—he used to get eight or ten buckets of milk. He would lay them out and the snake would drink out of them. They never knew it. One day my mother was outside, she used to have a garden right alongside it. So she come in and she sees the snake shhhhhhhh, and he slid into the walls of the shack.”

“My mother grabbed me and called to my father. ‘Tony, there’s a big snake in here and I’m afraid he’s liable to bite my boy.’”

Pupi picked up again. “So them days there was a man, according to my father and mother, known as San Pauliarro. His mother got in the family way on the night of St. Paul. You know the saint’s date. When San Pauliarro was born, he had two streaks of black across his shoulder, just like the cross. And he never went to school, never went any place. He would sit down and pray, and the snakes would come around. He gathered them snakes around the places where people were and took them out into the woods, so they wouldn’t bite anybody. He didn’t want them to be killed.”

“So my father said, ‘You wait, let’s wait till San Pauliarro comes over and he’ll take it away.’ In the meantime, my mother was afraid to sleep in the shack. It was more than a shack. My father used to make cheese there, ricotta, and provolone. They had 2-300 sheeps and goats.” “Plus,” he added dramatically, “some cows. So when San Pauliarro come around we says, ‘There’s a big snake living in the walls of the shack, come take it out.’”

“Then San Pauliarro kneels down, makes the sign of the cross and he called the snake, ‘Hey Cheech, come out now!’ And the snake comes, shhhhhhhhh sliding right out. My father is standing there; my mother had me in her arms.”

“Then San Pauliarro says, ‘why don’t you have that little boy charmed?’”

“My father says, ‘You better get out of here, I’m gonna…’ Anyway, he persuaded my father and mother to have the charming.

My father is standing there with the hatchet. He says, ‘If that damn snake bites him I’ll kill you.’”

“San Pauliarro said, ‘Don’t worry, he ain’t gonna bite. Don’t be afraid.’”

“So my parents put down a blanket and sat me in the middle. The snake comes, shhhhhhhhhh and he starts winding up all over me. And San Pauliarro’s kneeling down saying prayers. He got through and the snake slid off of me. My father gave him a ricotta for doing that, and he took the snake away. And the snake is following San Pauliarro around, shhhhhhhhhhhh, right alongside, right behind him.”

The men talked about playing cards. But we were stunned into silence. This story was like a fairy tale. Dad tapped his ring on the table. The ring was a snake curving around his finger, with tiny diamond eyes. “Where did you get that?” I asked.

“That’s for me to know and you to find out,” he said.

Those Tionesta weekends go on year after year. But I’ll never forget that first time. Pupi was so many things to us. There was no one else like him. He taught me how to hunt and play pool. Hardly anyone beat him at pool. He was always kind, and he really wanted to know how you were. But what happens if you are charmed by a snake? Is it like a spell? My 11-year old mind didn’t even know how to grasp this.

Today I take my own sons to Tionesta. Pupi came to the cabin every year until he was too old, with Frances hovering over him and his nitroglycerine pills. He lived to be almost 102.

This story was written by Lisa Bianco in collaboration with her brother John.