The Lost Hole of Oakmont

Founded in 1903, Oakmont Country Club is hallowed ground in American golf. In 1987, it became the first course to earn federal recognition as a National Historic Landmark. In August, it hosts its sixth U.S. Amateur and, in June 2025, its 10th U.S. Open. Aside from Augusta National, site of the Masters each year, Oakmont has hosted more major championships than any American golf course.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”388″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

Celebrated for its inherent toughness, Oakmont is the archetype of the “penal” school of golf architecture, captured best, perhaps, by its lightning quick, bafflingly undulating greens (the fastest ever, says Ben Crenshaw); its “furrowed” bunkers with high ridges of sand wide enough apart to ensnare errant shots; and the fact that Tommy Armour’s mark of 301 in the 1927 U.S. Open remains the highest winning score in any major golf championship since 1919.

An equal part of Oakmont’s legend is its integrity and continuity as an architectural site. Apart from the lengthening of several holes to adapt to technological gains in golf equipment, golfers today walk virtually the same routing of holes laid out by the father-son team of H.C. and W.C. Fownes, Jr. in 1903. No other championship venue — not even Shinnecock Hills in Southampton, N.Y., which antedated Oakmont by several years but later underwent major structural changes — can boast such a tight link between its original and current physical layout.

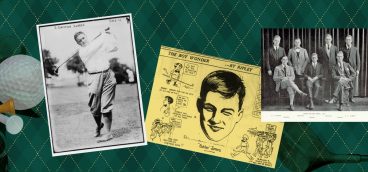

It was against this backdrop, steeped in history that former Oakmont pro and 2017 USGA Bob Jones Award winner Bob Ford, longtime Oakmont member Barry Hackett, and I were shocked to find an incredibly difficult hole, the 16th, that was expunged from the legendary course long ago.

* * *

To understand Oakmont, you have to understand the Fownes family. The entrepreneurial industrialists made their fortune buying, rehabilitating, and selling businesses, including selling the Carrie Furnace to Andrew Carnegie. Their unabashed aim was to make Oakmont America’s premier championship course, and their guiding principle was their stark philosophy that “a shot poorly played should be a shot irrevocably lost” — hence, the “penal” school of golf. From the time he took over as chairman of the Grounds Committee in 1911, W.C. embraced regular course modernization both to boost golf’s growing popularity as an American pastime and to reinforce Oakmont’s claim as the nation’s sternest golfing test. And that meant regularly tweaking every hole on the famous course.

Our discovery of what appears to be W.C.’s greatest tweak came about as I was working on a book about Dave Herron’s surprising victory over Bobby Jones in the 1919 U.S. Amateur. I was puzzled by something that happened in the infamous “megaphone incident” on the par-5 12th hole. With Herron in trouble following his second shot, Jones had a good chance to win the hole and extend the match. But just as Jones was starting his swing, a tournament marshal shouted loudly to quiet the crowd. This startled Jones and, essentially, he lost the match right there when he cold-topped his shot into a deep fairway bunker from which he was unable to extract his ball.

That bunker no longer exists, and I turned to Ford and Hackett to see if we could find where the bunker had been. After some sleuthing, Ford produced a 1925 aerial overview of Oakmont, and we also obtained a digital copy to magnify details. We easily located the huge bunker into which Jones had topped his second shot. Upon examining the old image further, we noticed that the green on No. 15 was 50-60 yards closer to the tee than it is today. And then came the mystery of what we’ve been calling “The Lost Hole of Oakmont.”

Try as we might, we couldn’t find the 16th hole as we know it today on the older photo. It took a while for us to absorb this. The current hole 16 simply didn’t exist in 1925. And in its place, we had “discovered” a hole at Oakmont that had been entirely lost to history.

The lost 16th had an entirely different tee, fairway and green. The green was situated well to the to the left and 25 or so yards behind the current 16th green. The old 16th was a 226-yard, par 3 that required a wooden club for even the best players in the world to reach the green through a very narrow entry. And the green was almost entirely surrounded by two of the most prodigious hazards we had ever seen.

On the green’s entire left side, extending halfway around its back edge and around 30 yards toward the tee, was an enormous, narrow, and deep trench with what appeared to be a touch of sand at the bottom. This “bunker” looked like something transported from the battlefields of World War I Europe. How a player was supposed to extricate himself from it — with the only club available at the time, a niblick (9-iron) — and in what direction he might be forced to hit his ball in order to play his next shot, was far from clear. In this hazard from hell, the natural inclination would be to pick up the ball and throw it out, without wasting fruitless energy or time.

Equally remarkable was the pit adjacent to the green’s right: a gargantuan bunker as treacherous as any of the hundreds Fownes created at Oakmont. Covering the green’s entire right side and beyond (indeed, almost up to the 17th tee), and extending perhaps 35–40 yards toward the tee before cutting directly into the fairway’s middle, the bunker was almost impossible for an average player to avoid. Deeper than most bunkers at Oakmont in the 1920s, it also extended to the edge of a grove of tall trees that might block a player’s swing. And because the entire fairway and green slanted sharply right, and because Fownes raked Oakmont’s bunkers into “furrows,” a slicer whose tee ball naturally curved left to right — the great majority of golfers, then and now — must have felt doomed.

In other words, if you were not a skilled enough player to thread the needle and find the perfect path to the green, No. 16 was all about learning to pick your poison. From where would you like to play your second shot? The inescapable trench on the left or the humongous bunker on the right?

Just how hard did the old 16th hole play during the 1920s? Fortunately, we have data from the best of them all, Bobby Jones, who won the 1925 U.S. Amateur at Oakmont in the greatest runaway victory of his entire career.

By 1925, most top golfers regarded Oakmont as the toughest course in the country. No one was expected to match its par 72 except on a lucky day. In fact, for the Amateur championship in 1925 — without reducing the length of any holes — Fownes lowered the par score at Oakmont by two strokes from what it had been (74) in the PGA Championship at Oakmont in 1922. He thus made par all the more difficult for the amateurs to achieve in 1925 than for the professionals in 1922. Not surprisingly, only one player managed to score under par (71) in the qualifying rounds, and in match play only Jones was able to break 70 (a 69 in the semi-finals).

A statistical indicator of how difficult No. 16 played in the 1925 Amateur is how Jones’s scores throughout the championship on No. 16 compared with his scores on the other eight holes of the back nine, Nos. 10-15 and 17-18.

Despite how well he was playing, Jones bogeyed No. 16 as often as he parred it. He averaged 3.5 strokes or a full half stroke over par. In fact, he only managed to score that well by chipping adeptly because he missed the green on his tee shot almost every time. (And if Jones, in one of his matches, instead of conceding, had actually finished playing No. 16 after losing his ball in the trees, his score would have been at least a 5 and his average would have risen higher than 3.5.)

So the old No. 16 in 1925 perfectly embodied the penal philosophy of W.C. Fownes, Jr. Playing at the very peak of his game, the hole still caused Bobby Jones fits.

Why, then, does this magnificent hole no longer exist? Indeed, why did Fownes begin plowing No. 16 under in late 1926 and build an entirely different par 3, from tee to green, prior to Oakmont’s first U.S. Open in 1927? And was the “new” No. 16 harder or easier than the “old”? Those intriguing questions we hope to explore soon.