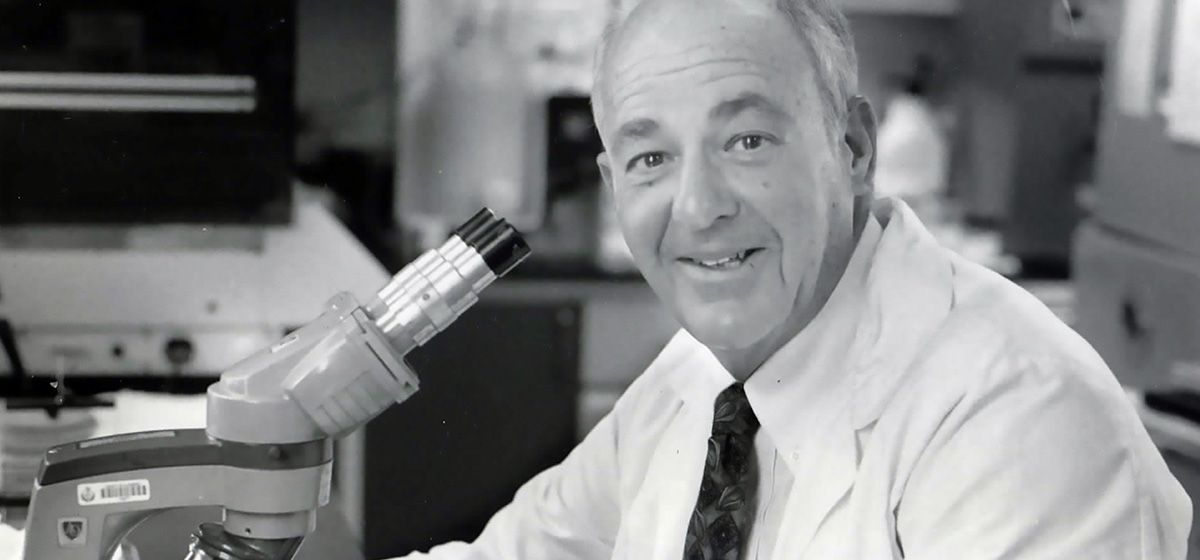

The Life and Deaths of Cyril Wecht

Stepping into his office to interview Cyril Wecht for a profile I had been commissioned to write for Pittsburgh Quarterly, I expected to encounter the intense, blustering and contentious person who had so often been depicted on the evening news. To me, at the time, Cyril was just another loud-mouthed local public official who had faced down corruption charges, and who never met a TV camera he didn’t like.

Like many Pittsburghers, my take on Allegheny County’s indefatigable and loquacious coroner had been shaped by the local media’s selective portrayal of him. But the man I found that day turned out to be a self-aware, amazingly sharp, courteous and overworked gentleman in his eighties, who had suffered the slings and arrows of a wide array of political opponents and other detractors for decades, and who definitely had a desire to tell his side of his story.

Born March 20, 1931, in Bobtown, Pa., and raised in Pittsburgh’s Lower Hill District, Cyril experienced a happy and busy youth. He helped at his family’s modest grocery store. He excelled in school, endured intensive violin lessons, and participated in a host of sports—not to mention his share of teenage hijinks.

Typical of adolescent boys in his era, Cyril and his friends had their own rites of passage, one of which was to sneak into the Allegheny County Coroner’s Office to view any dead bodies that might be on display. Sometimes the bodies lay on gurneys waiting to be viewed for purposes of identification by family, or for pickup by local funeral directors. Cyril admits that it was a little frightening because some of the fresher bodies were still dripping blood.

Like so many who hailed from blue-collar families during the years of World War II, Cyril knew that success in America would come only as a result of personal effort and tenacity. He had no cushion, no inheritance, and thus became driven, passionate and ceaselessly active, desirous of any and all knowledge and experience. And while his life’s course would twist and turn and his fortunes rise and fall, his belief in himself never wavered. His life is a testament to the resiliency of the human spirit.

Over lunch one day after my profile of him was published, Cyril went on in great detail about the events of his life, including some of the many famous cases in which he had played a part: the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and his brother, Robert; the case against Claus von Bülow, the foreign-born socialite who was convicted of the attempted murder of his wife (the judgment for which was overturned later with Cyril’s help); the unresolved death of JonBenét Ramsey; the incineration of the Branch Davidians at the hands of the U.S. government; the convictions of “family annihilators” Scott Peterson and Lyle and Erik Menendez; and the curious deaths of music stars Elvis Presley and Kurt Cobain.

But despite his impressive casework, Cyril spoke most passionately about the federal corruption case that had been brought against him in 2006 for the alleged improper use of his public office. Mind you, the man has a photographic memory for names, places, dates and, sometimes, even phone numbers. And as he continued relating all the details he could remember about his sensational trial, I interrupted and said, quite innocently, “Maybe you should write about that,” to which Cyril responded, “But I don’t have the time. I wonder if someone would help me with that?” I said, “Well, I might just be willing to take that on.”

In approaching Cyril and his life story, I began not with the legend but with the man himself. Before conducting interviews with any of Cyril’s many and impressive colleagues and supporters—Oliver Stone, Alan Dershowitz, F. Lee. Bailey, Alec Baldwin, and Geraldo Rivera, to name some—I spent more than 40 hours collecting the thoughts of Cyril himself, tracing his personal history and covering the highlights of his career, in and out of the spotlight. But it wasn’t until about hour number 15 that I witnessed him sigh, look down at the floor, and begin to tell me not what he thought about his life and career, but rather what he felt. It was only then that I knew we had a book in-the-making. And that book, which Cyril and I wrote together, is now available and titled, “The Life and Deaths of Cyril Wecht.”

All told, as a coroner and private consultant, he has probably conducted more autopsies—21,000—than any other forensic pathologist in the country. He has also reviewed and/or supervised another 41,000. But even after nearly 60 years of work in morgues and laboratories, he says there are things to which one simply can’t get used to, including some of the sights and smells. But it’s the work that he does. For Cyril, it is most important never to lose cognizance of the fact that he is dealing with dead human beings. Somebody, somewhere, at some time, loved these people, so all autopsies, no matter of whom, must be handled with dignity and respect.

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about Cyril is his energy level. In the end, neither of us could account for it. It just is. For example, in 1975, several years after the bombshell story was published in The New York Times about President Kennedy’s missing brain (for which Cyril was the source), he was in Colorado skiing with his family during his kids’ spring break when he got a call from TV host Geraldo Rivera, whom he had never met, asking him to appear on a program about the JFK assassination. He accepted. Cyril started by driving his rental car from Vail to the Denver airport. Back then, he had to traverse a high mountain pass to get out of ski-country. When his car got stuck, a trucker gave him a lift. He flew to New York, appeared on TV, had dinner with Geraldo at a French restaurant and then dashed back to the airport for a late-night return to Denver, Vail and his family.