The Great Migration Begins

Across the sky, everything is moving. Fall migration actually begins in August when the first waves of long-distance travelers begin to push south.

Warblers, hummingbirds, waterfowl, shorebirds and hawks begin southward journeys. Some have nested and fledged chicks over the summer in sight of the Point, Flagstaff Hill, the Highland Park Bridge, the furnace chimneys at the Waterfront, the Laurel Highlands, maybe your back yard. They feasted on the abundance of a western Pennsylvania summer and now follow food and warm days south as the northern hemisphere tilts away from the sun. Others are just passing through. To the human watchers of migration, it is the movement of raptors that can be the most impressive.

To understand raptor migration, you have to appreciate geology. We live just west of some of the biggest geologic raptor highways in our country. Look at a topographic map of Pennsylvania; see the curves that run northeast to southwest? Those are the mountainous lanes of an avian autobahn that speed birds south this time of year as swiftly as a jaunt on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. In fact, the pike rises and falls over much of that same terrain: Tuscarora Mountain, Blue Mountain, Kittatinny Mountain. Every tunnel we drive through cuts beneath a bird superhighway above. Windy updrafts and thermals provide ease of passage, allowing migrants to conserve energy during long trips. Fewer wing beats, fewer calories burned, more fat to make the full journey.

Raptors pass over the state in abundance: on September 16, 2018 alone, 4,094 raptors flew by the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch on that single day, mostly in what observers called a robust flight of 3,972 broad-winged hawks. They also saw that day, “3 falcon species: 12 kestrel, 3 merlin, 1 peregrine. 37 bald Eagles—1 shy of record set 3 days ago. 1 bald eagle with stick. Merlin chasing broadwing.”

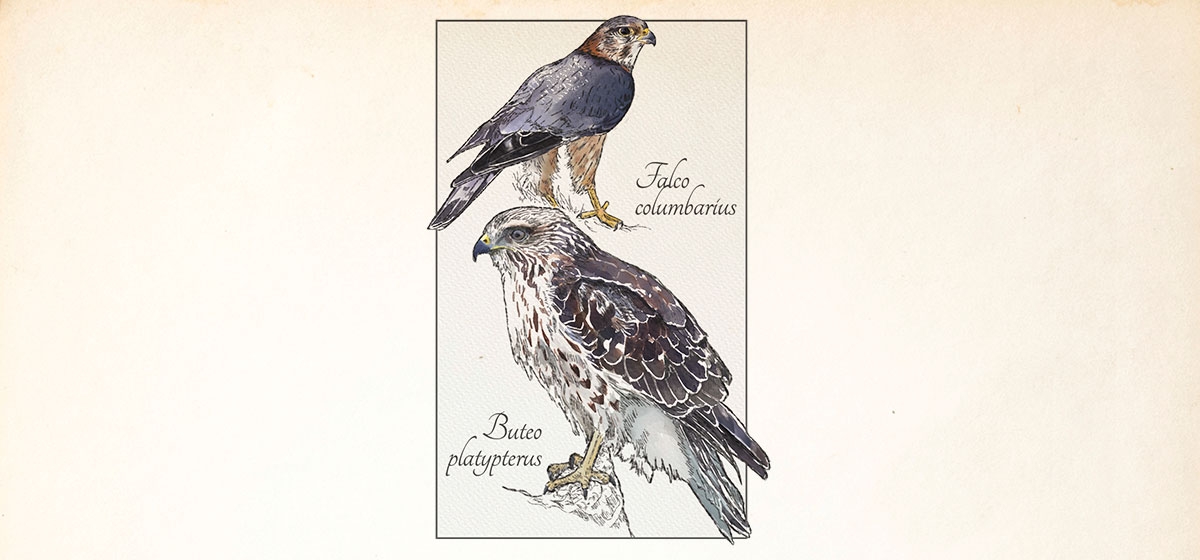

Thanks to local nesting pairs and webcams, Pittsburghers are increasingly familiar with peregrine falcons and bald eagles. Merlins are small, pointy-winged falcons with streaked chests and underwings that are fast fliers. Smaller than a crow, they are generally dark with narrow tails. Perched, they’re attentive and sharp-eyed. On the wing, they’re just a blur. They feed on small birds like the abundant house sparrow or various nestlings, bats or small mammals. Kestrels are even smaller falcons with lovely, hued plumage.

And the ubiquitous broad-wing? Large swirls of them, called kettles, reveal birds whose wings span three feet or more. With brownish heads, streaked chests, and black and white banded tails, their high, thin whistles are diagnostic. Usually found in forest interiors, migration brings them out high above the treetops where aerial conglomerations gather as they trek annually toward South American wintering grounds.

At the Allegheny Front, on a scarp about 2,800 feet above sea level, is an overlook that provides eye-opening access to their avian world. Sometimes birds fly by just overhead, sometimes higher or lower depending on wind and weather. I’ve seen many flights of raptors there without the crowds (or amenities) of the famous Hawk Mountain, several hundred miles farther to the east. This fall, get up close with the migrants. The hawk watch is about a two-hour drive from Pittsburgh, past Somerset and near Central City, and totally worth the trip.

Get directions to the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch at www.wbnc.net/front.htm. Track the migration of raptors online at www.hawkcount.org or join the PABirds listserve for daily reports via the Pennsylvania Society for Ornithology at pabirds.org.