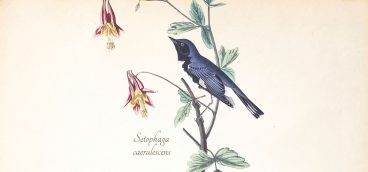

One April morning when I was watching my feeders, I noticed a woodpecker on a branch. At least I thought it was a plain, old woodpecker. Black and white plumage, chisel-like beak. But there was red on the front of its face and chin. Not the back-of-the-head, red splotch of the male downy or hairy woodpecker. Peering more closely, the pattern of the back was more striped than dotted, and the wing had a long, white blotch. And then there was that color on the chest. I knew I had a new species: a yellow-bellied sapsucker!

As sap begins to rise on warm days from roots to buds, sapsuckers return from migrations that can be to areas as close as the mid-Atlantic and southern United States and as far away as Mexico and Central America. Males return first. For unknown reasons, females prefer longer distance migrations. They both travel the night skies.

“You yellow-bellied sapsucker!” I thought I remembered Yosemite Sam saying it to Bugs Bunny. Or Daffy Duck uttering it with his lisp. But search as I might, I couldn’t find a video clip. Apocryphal? But I recognized a real, living one when I saw it. Indeed, the belly has the faintest wash of yellow.

Yellow-bellied sapsuckers tap into our trees by drilling rows of small wells into the inner xylem and outer phloem (remember those words from biology class?). The wells promise nourishing sap, also attracting hummingbirds who time their spring return to that of the sapsucker’s.

Sapsuckers tend shallow rectangular wells for their regular meals and can get as much as 20 percent of their dietary needs from sap, the rest from gleaning insects attracted to the wells or hiding in bark crevices like many of their woodpecker cousins. That morning, I ran outside with my camera to snap two pictures of the same bird, now exploring my yard, as it forever decorated an evergreen with five rows of round drill holes. The species prefers deciduous trees, especially young birches and maples, so this was just exploratory, a sapsucker’s spring fever. There was still a dusting of snow on the ground. Call it hopeful prospecting.

Later in the spring and into summer, sapsuckers pair up to nest in tree cavities across Pennsylvania’s northern tier. Males spend several weeks excavating a small entrance hole and a chamber some 10 inches deep, a nursery that may be reused for years. Eggs are white, typical of interior nests hidden from view, and number four to six in a single brood. After a fortnight’s incubation, initially blind, featherless chicks grow quickly, flying the nest in a month or less.

Parents teach well-drilling techniques to their children, passing down the family business generation to generation. In the commonwealth, sapsucker populations are sizable at about 100,000 birds and increasing. Though they may only be passing through Pittsburgh on their way to more forested areas, sapsuckers’ tolerance for edge habitat and young tree stands suggests a kind of adaptability that serves them well. Keep your eyes open this spring for this memorably named bird!

Email your cartoon clips, avian encounters, photos or questions to PQonthewing@gmail.com.