The Arts Engine

On a cold spring night in April, arts traffic streamed along Penn Avenue in several frenetic directions. Downtown, patrons for the PSO’s performance of Bach’s beloved Brandenburg Concertos poured out of restaurants toward Heinz Hall, dodging ticket-holders for the sold-out “Book of Mormon” at the Benedum Center. Four miles miles east, the cheap end of Penn Avenue was having an arts throw-down of a different sort.

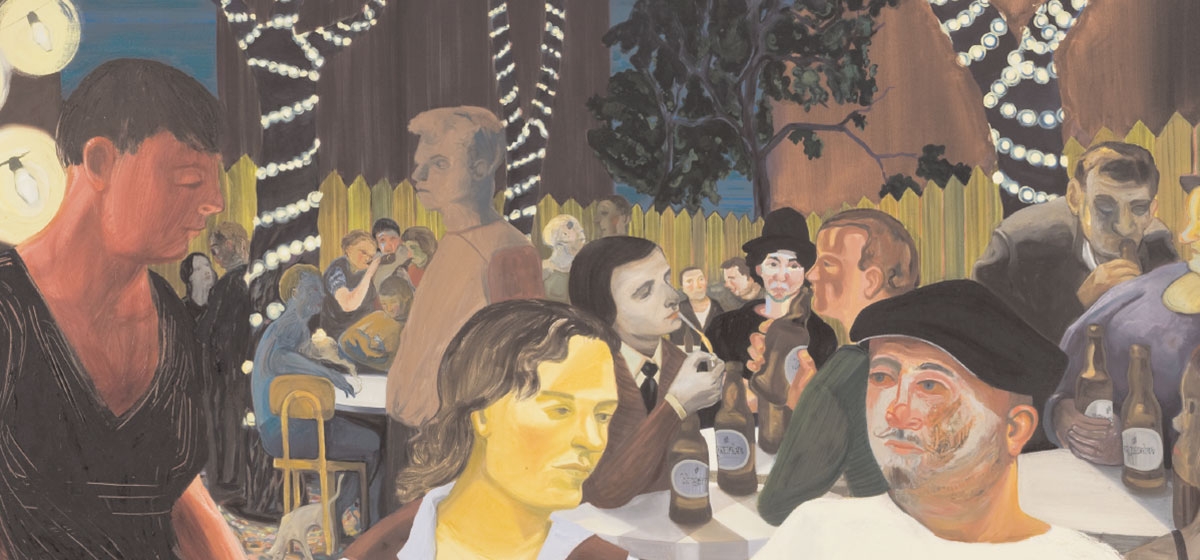

Jean-and-hoodie-clad couples, many pushing strollers, were streaming to the GeekFest/Green Initiative, a street fair in Garfield. The dressed-down DIY event featured projects such as Knit the Bridge, a community effort to “yarn-bomb” an Allegheny River span with colorful wool panels, and a marshmallow roast outside the Pittsburgh Glass Center. And in between the two, the Strip District nightclub Static was hosting “Mercury Soul,” an unlikely mash-up of symphony musicians and techno music—DJ’d by the PSO’s resident composer, 36-year-old Mason Bates—that had a sweaty crowd of 800 dancing and drinking past midnight.

The confluence of events would have been unimaginable in 1984, when Heinz Hall was a lonely, opulent beacon; the artistic offerings of its neighbors along Penn and Liberty avenues were confined to massage parlors. Three decades later, Pittsburgh’s Cultural District has been widely recognized as one of the country’s most successful examples of arts-generated economic development. With ample help from the city’s largest foundations, the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust is both an arts programmer and one of the city’s largest landowners.

Today, more than 2 million people a year visit the district, supporting not just performance, but galleries, cabarets, restaurants and housing throughout the core. The 14-block district has an annual economic impact estimated at $250 million.

Now, gritty neighborhoods such as Garfield and the North Shore are borrowing Downtown’s philosophy of using culture to ignite street life, and Downtown institutions are getting schooled on programming by the youthful neighborhood scene.

Pittsburgh has met the challenge—shared by other mid-American cities—of growing an art audience in a slow-growth city with an aging population. And while the amplified offerings of the seven main downtown presenters (the Trust, Symphony, Ballet Theatre, Opera, Public Theater, Dance Council and CLO) have doubled their overall audience in the past 10 years, arts leaders are pushing ahead with strategies to lure a younger, more diverse audience.

Under Kevin McMahon, who succeeded founding CEO Carol Brown as president of the Trust in 2001, the Trust has forged alliances with annual events, notably the Three Rivers Arts Festival and international festivals for jazz and children’s arts. This fall’s Festival of Firsts will bring a bill of international premieres. The Trust has streamlined joint marketing and administrative efforts, and built galleries and performance programming. Downtown theaters now host 1,500 events each year.

But as Downtown arts establishments grew over the decade, their tux-and-mink-coat demographics shifted. The number of young people ages 20–24 living in the city jumped over 22 percent during the past 10 years.

The resulting shift in tastes to more experimental and socially conscious programming has traditional institutions trying to diversify both programming and audience. The symphony, delighted by the turnout at its Mercury Soul event, offered online discounts to the next weekend’s Heinz Hall performance to lure back the nightclub crowd.

“If you look at the national scene,” McMahon says, “we’re all worried about audience development—making the arts accessible to more people.”

The Cultural Trust has subsidized both Bricolage and Pittsburgh Playwrights Theater, which share a small Trust-owned space. McMahon says its investment in the two fledgling companies is a sign of strength. “We’ve spent time and resources trying to help them along. Likewise on the visual side. Our free gallery crawls and jazz festivals are indicators of more diverse participation.”

Despite the launch of Downtown’s new August Wilson Center for African American Culture in 2009, African-American respondents in a recent poll were 33 percent more likely than other races to view local cultural offerings as unsatisfactory. Mitch Swain acknowledges the problem. “Over the last few years people have recognized that Pittsburgh is a great arts town,” says the CEO of the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council, an advocate for over 200 arts groups in southwestern Pennsylvania. “There’s a continuation of great foundation support, and great programming. But not everyone who lives here feels that way.”

That realization, Swain says, has raised arts groups’ consciousness. The Pittsburgh Foundation and Heinz Endowments are in the second year of support for the Advancing Black Arts Initiative, a $650,000 pool of funds for artists and programs.

Artists and Equity

Beginning in 1998, artists living in lower-income communities strung along the eastern end of Penn Avenue thought that arts could spark a renaissance, as they had Downtown. Earlier research from Artists in Cities, a national nonprofit, showed that 10 percent of all Pittsburgh artists lived in the ZIP codes near Bloomfield and Garfield. The adjacent neighborhoods had different ethnic identities but similar problems: crime and decay.

“Businesses were leaving, so they were willing to try,” recalls Jeffrey Dorsey, the first director of the Penn Avenue Arts Initiative. Local foundations backed the joint project by the neighborhood development groups.

“We were created from the environment we were in—cheap housing stock,” says Dorsey. The Community Design Center of Pittsburgh enlisted architects to create a master plan for seven blocks along the street, and the initiative acquired 16 properties. An art deco car dealership was rehabbed as loft studios for low-income artists. Arts entrepreneurs got micro-grants to rehab row houses into galleries and homes. The Initiative added façade and renovation grants. Two dozen artists and arts groups, including the Pittsburgh Glass Center, colonized the street.

“We gave artists an equity position—we were the first project in the country to do that. It was intentional, and that encouraged other developers,” Dorsey recalls. Apartments for seniors and youth programs helped gain community trust. New commercial development followed. Today, Pittsburgh’s most-talked-about new restaurant, Salt of the Earth, has joined the business district. And while Penn Avenue could use a few more busy storefronts—and a fresh coat of asphalt, due this summer—the street celebrates each month with “Unblurred,” an arts open house.

“The initiative is over. It’s a place now,” Dorsey says.

Urban studies theorist Richard Florida recently recalled joining Dorsey for a panel discussion at the Warhol Museum. Then a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, Florida was developing his theories about the creative class. Looking back, Florida says serving on the boards of two North Shore institutions, the Warhol and the Mattress Factory, was “a life-and-career-changing event.”

“People were talking about Downtown and high-tech development. But the really interesting energy was coming from the arts and culture communities. Younger people wanted more active expressions, embedded in other activity, like along Penn Avenue. Those kinds of activities were beneath the radar, but they were critically important.”

The North Shore still shares many of the urban ills that beset Bloomfield-Garfield, but it has an asset most city neighborhoods would envy: the Charm Bracelet. A loose consortium of a dozen cultural institutions in a one-mile radius, many housed in elegant landmarks that date to the 19th century, the project is trying to reunite a racially and economically fractured community. Some partners, like the Warhol and the Mattress Factory, or the Children’s Museum and the Carnegie Science Center, have overlapping interests; all have been working since 2006 to collaborate on building both community and audience.

City of Asylum/Pittsburgh extends that effort by giving exiled writers a safe house—literally. Along a modest alley next door to the Mattress Factory stand row homes boldy painted with words and images from the defiant residents, whose living expenses are covered for two years. COA also publishes a lively online journal and hosts international readings and events. Henry Reese, who founded the Pittsburgh branch of the network in 2004 with his wife, artist Diane Samuels, recently announced COA’s expansion to North Avenue, the neighborhood’s long-derelict main street.

Alphabet City will open next year as the anchor tenant of the former Masonic Temple in the Garden Theater block. Reese says it will be a “home for all things literary: a bookstore, as well as a free book-distribution program; a recording/broadcast-enabled performance space for readings and performances; space for workshops and classes; and a restaurant with Internet access.”

“We think we’re a bridge between the different residents who don’t occupy the same space but live in the same communities,” Reese says.

Redeveloping the block has eluded city government for the past 20 years. Once again, the arts may be the right engine.