In the late 1990s, Teresa Heinz and others gazed at the new Alcoa headquarters and its North Shore neighbor, the new Lincoln Properties. Both occupied key riverfront spots. But compared with the standard-setting Alcoa structure, the residential development looked like a Motel 6.

An idea was born—to conceive a holistic vision of the riverfront with excellence as its hallmark. The initial assignment of the Riverlife Task Force was to create a master plan for Pittsburgh’s riverfront that would seize what historian David McCullough called a “once-in-a-century opportunity” to make Pittsburgh’s waterfront among the most spectacular in the world.

Now, 10 years later, what is known as Three Rivers Park—from the West End Bridge on the Ohio to the 31st Street Bridge on the Allegheny and to the Hot Metal Bridge on the Monongahela—is about 65 percent complete. Three current projects will raise that to 85 percent: the South Side Works Riverfront Park, which will scale down to the water with trails, landscapes and performances spaces; the Convention Center Riverfront Park, which will connect Point State Park, the Cultural District and the Strip District and feature a major water landing; and the Mon Wharf, with its new riverfront trail and coming connection to the Eliza Furnace Trail, which will connect with the Great Allegheny Passage and Washington, D.C.

What’s now known simply as Riverlife shows what can happen when the public, private and nonprofit leaders unite around a vision for change and excellence on a world-class scale.

Among those deserving credit are former Mayor Tom Murphy, who embraced the initial idea and appointed Paul O’Neill and John Craig Jr. as its first co-chairmen. Also there at the beginning were Heinz, Elsie Hillman, Max King, Mike Watson and others. Essential early converts were the riverfront’s major property owners—such as the Buncher Company’s Tom Balestrieri, the Gateway Clipper’s Terry Wirginis, the Carnegie’s Ellsworth Brown, and the Steelers’ Art Rooney II. Overseeing it all has been Riverlife Executive Director Lisa Schroeder.

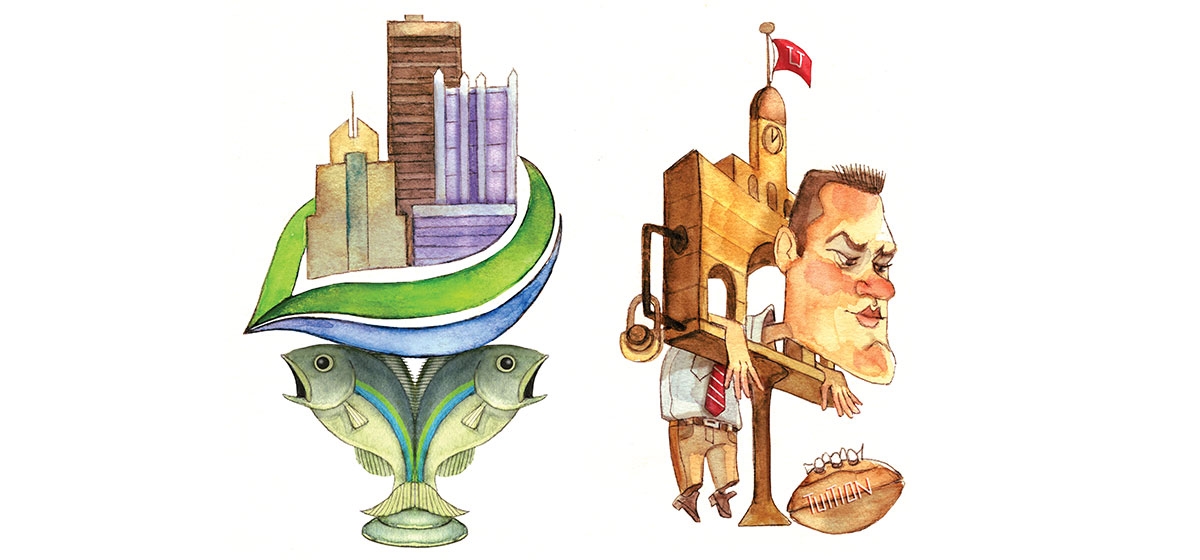

In the stocks: Mayor Luke Ravenstahl, tuition tax

There are right ways and wrong ways of trying to balance the City of Pittsburgh’s budget. Pittsburgh Mayor Luke Ravenstahl attempted to raise roughly $15 million by levying a 1 percent tax on the tuition paid by university students. The mayor’s actions did not represent good leadership. Worse, they indicate rash disregard for developing the kind of partnerships in progress that have highlighted Pittsburgh’s history and that the city needs to forge its future.

First, taxing students during a recession is not the message Pittsburgh should be sending to young people and the world. Pittsburgh’s students and universities are among the city’s few best assets—not its few best targets.

Second, the tax would have been found to be illegal and shot down the moment it reached Harrisburg. Due diligence was not done by the mayor and his advisors.

Third, strong-arming and threatening your biggest institutional partners isn’t just bad form, it’s bad business. The mayor said he would drop his tax proposal if the universities agreed to contribute $5 million more to city coffers. No one worth his salt responds to a threat, and our university leaders lined up against the mayor. After being stared down, the mayor tried to save face by announcing that the universities had agreed to increase their contributions to the city. Unfortunately for the city, the lasting yield of his tactics will be much more ill will than new dollars.