As a child growing up in Pittsburgh in the ’50s, I thought that Lawrenceville was named for our mayor and that the soldier statue at Butler and 34th Street was David L. Lawrence as a young man.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”17″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

Umm, wrong.

The immortal soldier who guards “Larryville” from his circular pedestal at Doughboy Square is a World War I memorial — one of the most enduringly beautiful in the nation. And the namesake of the colorful born-again community just east of Downtown was Capt. James (not Mayor/Governor David) Lawrence.

Talk about immortal: Do the words “Don’t give up the ship!” ring a bell? They were Capt. Lawrence’s last. During the War of 1812, Lawrence (1781-1813) commanded the U.S.S. Hornet and captured the British ship Peacock at the tender age of 32. He was rewarded with the command of the 49-gun frigate U.S.S. Chesapeake, which in June of 1813 engaged the British frigate Shannon off the coast of Boston. But Lawrence’s young Yankee crew was untrained, while HMS Shannon’s was the Royal Navy’s best. In less than an hour, the Chesapeake was overwhelmed and its captain mortally wounded. As Lawrence fell, he shouted, “Tell the men to fire faster and not to give up the ship!”

The short version has been a more quotably convenient battle cry for American sailors ever since.

The heroic Lawrence was still much in people’s minds a year after his demise, in 1814, when Pittsburgh business pioneer William Barclay Foster acquired 121 acres of property and founded the borough he called “Lawrenceville” parallel to the Allegheny River from what is now the Strip District northeast to Stanton Heights.

Its founder would not recognize the post-industrial place today, just as most folks would not recognize the name of William Foster. But everybody recognizes the name of his (and Lawrenceville’s) favorite son— composer Stephen Collins Foster —who was born there on July 4, 1826. What an incredibly patriotic birthdate for America’s greatest pop-tunesmith: It was the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, as well as the day its two greatest signers, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, both died.

The prodigious Foster (who died tragically penniless in 1864) is the only composer to have written not one but two state songs, “My Old Kentucky Home” (Kentucky) and “Swannee River” (Florida). (He would have had a third, out on the West Coast, but “Oh! Susanna” narrowly lost out to the lame ditty, “I Love California.”)

Cut to another musician exactly a century later: Stephen Foster would have been baffled by the sight of sequins in Lawrenceville, but it was there that Liberace believed God worked a miracle that saved his life. The fabulously fey pianist was taken to St. Francis Hospital after becoming violently ill during a 1963 Holiday House performance in Monroeville. He credited the hospital’s superb nun-nurses as well as God with his recovery from a near-fatal reaction to cleaning fluid used on one of his glittery garments.

The Lord works in strange ways everywhere, but especially in Lawrenceville (current population 10,500), an edgy area with a gloriously gritty past. Annexed to the city in 1868, it was first populated by German, Polish, Croatian and Slovak immigrants. In the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries, it was home to all manner of manufacturing industries including U.S. Steel, Union Switch & Signal, Westinghouse Electric, Iron City Brewery, and the Heppenstall steel works, whose massive (and surely haunted) mill buildings remain there. The first incandescent lamps were manufactured in Lawrenceville in 1881. The airbrake was invented and first manufactured there.

Nowadays, it is home to Carnegie Mellon University’s NASA-funded National Robotics Engineering Center (in a reoccupied factory near the 40th Street Bridge), a terrific stock of pre-Civil War row houses and cutting-edge artists who coexist with families descended from the original European immigrants.

Lawrenceville is, simply, Pittsburgh’s fastest-growing-and-changing neighborhood for old and new generations alike. Its revitalization has attracted more and more newcomers to the narrow streets and prime single-family homes. Yuppies have been snapping up the working-class brick bargains between 40th and 45th (median price $56,000), while cash-strapped artistes can find cheap rents in the wood-framed tenements.

The past decade has brought new entrepreneurs and trendier wares to the old storefronts, an increasing number of them beautifully refurbished in the “16:62 Design Zone” between 16th and 62nd streets, with its eclectic mix of artists’ lofts and studios, architects’ offices and craftsmen’s workshops — of which, more later.

A little more history, first.

By 1860, the Allegheny Arsenal on Butler Street was the principal fabricating facility for military ammunition in America. It was not uncommon for Arsenal warehouses to hold 5,000 artillery shells, 1,300 barrels of gunpowder and an astonishing 8 million bullets at a time, according to Lawrenceville brother-historians James and Jude Wudarczyk.

The arsenal was built in 1814 — the same year of Lawrenceville’s founding — on 38 acres between 39th and 40th streets. Today, it’s the site of a baseball field in Arsenal Park. But in 1862, it was the site of the greatest civilian tragedy of the Civil War.

At that time, the arsenal employed some 1,100 who loaded cartridges and grapeshot and produced gun carriages, caissons, belt buckles and other supplies needed by Union soldiers. Women and young girls had largely replaced the men who formerly worked there as well as the recently fired boys who had left matches around the gunpowder.

On Sept. 17, 1862 — payday at the arsenal — the workers were lined up for their money when three huge explosions occurred. Seventy-eight, mostly young women and teenage girls, died. The Pittsburgh Daily Post reported fleeing victims, covered in flames: “The ground was strewn with charred wood, torn clothing, grape shot, exploded shells, fragments of dinner baskets, steel springs from girls’ hoop skirts and melted lead.”

A coroner’s jury later declared the explosions were due to negligence by arsenal officials for allowing loose gunpowder to accumulate in the magazine buildings. Even at the time, the Arsenal explosion received pathetically little national attention: It took place on the same day as — and was dwarfed by news of— the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single day of the Civil War.

Most of the victims were buried in a common grave, whose monument reads: “Tread softly. This is consecrated dust. Forty-five pure patriotic victims lie here. A sacrifice to freedom and civil liberty. A horrid memento to a most wicked rebellion.”

The memory of them is kept alive by the Lawrenceville Historical Society and its 2007 lecture series’ presentation, “An Appalling Disaster: The Allegheny Arsenal Explosion” (with historian Allan Becer, will be March 15, 7 p.m. at Canterbury Place’s McVay Auditorium, 310 Fisk St., free to the public).

But Pittsburgh pays homage to them regularly at their common burial site, located in Lawrenceville’s vast, otherworldly Necropolis — Allegheny Cemetery, at 4734 Butler Street. A timeless and haunting place containing two centuries of exquisite funereal art, Allegheny Cemetery was one of the first designed to provide an idyllic escape in death from industrial life. Some 125,000 are buried there, including the likes of Pittsburgh Gazette editor Neville B. Craig, famed actress Lillian Russell (who married Pittsburgh Leader publisher Alexander Moore), and the Fosters père and fils alike.

Lawrenceville itself, on the other hand, is very much alive and well. Though still scarred by urban neglect, Pittsburgh’s most diverse neighborhood is on the rebound with a renaissance of new businesses, restaurants and restoration efforts to revitalize the riverfront corridor between 40th and 62nd streets. Urban homesteading and ambitious development plans represent Larryville’s chance to finally address such nagging problems as cleaning up defunct industrial sites and solving traffic and access difficulties, thanks in no small part to the Community Design Center of Pittsburgh.

Since starting as a group of volunteer architects and VISTA workers, the CDC design fund has granted $850,000, which has generated $73 million in investments. CDC has taken chances on granting money for ideas that most sources wouldn’t touch. Its $12,259 master planning grant to Lawrenceville was a quintessential gamble.

The result is the “16:62 Design Zone,” a cooperative niche marketing initiative spearheaded by the Lawrenceville Corporation to promote design-related businesses and help developers find new uses for the forlorn buildings and neighborhoods throughout Lawrenceville — start-up and established enterprises alike. With funding from the Pittsburgh Partnership for Neighborhood Development (a supporting organization of The Pittsburgh Foundation), the idea was to bring new businesses and residents into the Lawrenceville area between the 16th Street and the 62nd Street bridges. (The actual enterprise zone is somewhat larger, but it was decided to use the two well-known bridges as brackets because they would stick in the public mind.)

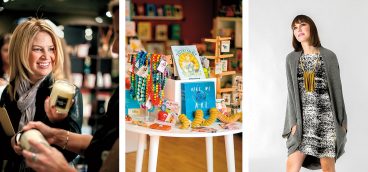

In less than a decade, the 16:62 Design Zone has established itself as Pittsburgh’s interior design district. The more than 100 shops, studios, service firms, showrooms, manufacturers and galleries in the Zone have turned Lawrenceville into a magnet for avant-garde residents and customers in search of products and services to create or renovate their homes and workplace—from architects to custom furniture makers.

The design businesses are housed in buildings ranging from a turn-of-the-century firehouse (now an architectural millwork company) to an 1860s stable (now a home-furnishings store). Lawrenceville’s offerings attract upscale merchants as well as “fringe” artists, as it transforms itself from an old industrial area into a hip habitat for those seeking art, antiques and gift boutiques.

“We have gone from a former steel town to postindustrial chic,” Joe Kelly, one of the first to recognize the area’s potential, told reporter Jan Ackerman. For 15 years, Kelly Custom Furniture & Cabinetry—located at 5239 Butler St. in a Victorian storefront, formerly a haberdashery—has crafted upscale pieces for homes and offices. He called Lawrenceville “the last frontier of the city,” with the biggest riverfront around and the good fortune to escape redevelopment efforts.

Missing out on the massive amount of redevelopment money doled out to local communities in the 1960s and ’70s was a blessing in disguise for Lawrenceville — and posterity. Instead of being torn down and replaced by modern monstrosities, the community’s historical and picturesque old housing stock remained standing, patiently awaiting the new owners and renovations of a more sensitive 21st century.

A sample of successes:

Rosemarie Perla purchased a decrepit century-old twin row house in Lawrenceville in 2005 for $30,000. The three-story brick structure, circa 1860, was thought to have been a tavern and Conestoga wagon stop on the Pittsburgh-Greensburg turnpike. A transom over glass doors framed the house’s backdrop—the spires of St. Augustine Catholic Church on 37th Street. Gutted by previous owners, it was uninhabitable, but Perla’s 13-month renovation was so dramatic she won first place in the Renovation Inspiration contest co-sponsored by the Community Design Center of Pittsburgh. Perla used local merchants and craftsmen. Gerald’s Forge on Butler Street handcrafted the artistic ironwork while Artemis Environmental Building Materials, a “green” supplies store at 3709 Butler St., provided the bamboo butcher block for her cooktop, the recycled glass tile in her master bath and the bamboo floors.

The 1880s vintage, three-story red brick Victorian at 146 45th St. had been a popular corner grocery store for a century, until its last grocer-owner gave up in 1979. By 2005, it was a vacant eyesore, condemned to be knocked down until Triple H Development, a small Lawrenceville firm led by Chris Hollingshead, paid $7,900 for it at a sheriff’s sale and invested $150,000 to turn it into three apartments. Triple H (for “No-Hassle Historic Homes”) is committed to saving architectural details such as trims, mantels and banisters—and, in general, finding solutions that don’t involve wrecking balls.

Penn Avenue’s rehabilitation has not been as dramatic as Butler Street’s but got a big boost with the emergence of the seriously trendy Brillobox. Its 15 minutes of Warholesque fame seems to have been extended indefinitely, to the gratification of its founders/transplanted New Yorkers Renee Ickes and Eric Stern. Upstairs from the 1950s-looking bar is the itinerant home to avant-garde bands from across the country.

Would that we had space for a full list of exciting new Lawrenceville locales to discover. It would include Scavengers Antiques & Collectibles (3533 Butler St.), T’s Upholstery Studio (3611 Butler), Piccolo Forno (3801 Butler), Crazy Mocha (4032 Butler), Fe Gallery (4102 Butler), Hambone’s Restaurant-Lounge (4207 Butler), the Gallery & Griffin Galleries (179 and 183 43rd St.), Perk Me Up (4407 Butler), DNA Blue Collar & Trinity Galleries (4719 and 4747 Hatfield St.), and dozens more. Artists and Cities Inc., a nonprofit, is converting the former ice house factory on 43rd Street into 32 studios for artists. The proprietors of these and other embryonic establishments credit Lawrenceville’s diversity, historic architecture and preservation, cost-effectiveness and supportive neighbors to the Design Zone’s success.

The obvious moral of this story: “Don’t give up the ship — or Lawrenceville!”