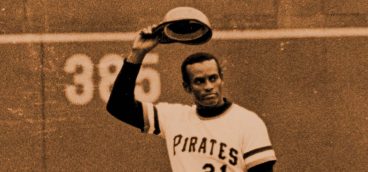

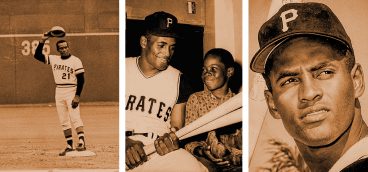

Remembering Roberto Clemente

When you are seven, everyone on your team is a hero. Some may be greater than others, but they all are heroes. And not just the players.

I do not know if the Pirates have a traveling secretary today. If they do, I do not know who it is. I do not know what a traveling secretary does. But I do know that in the 1960s, the traveling secretary of the Pittsburgh Pirates was Bob Rice and, as far as I was concerned, that made him a great man.

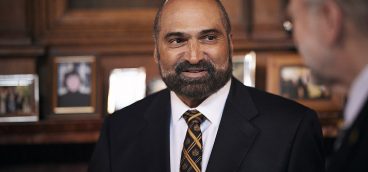

The Pirates team physician was Dr. Joseph Feingold. This important fact was specified on virtually every Pirate broadcast of the 1960s. Dr. Feingold, too, was a great man. Not just because he was the Pirates’ team physician, although that would have been reason enough. Because he was, as I recall it, the man who arranged the Rodef Shalom Congregation Father, Son and Daughter event after Sunday School one morning 57 years ago. It was not an elaborate affair. Just a young man sitting in a chair in the middle of a reception hall and a long line of girls and boys politely waiting to meet him. I don’t even think that there were any refreshments.

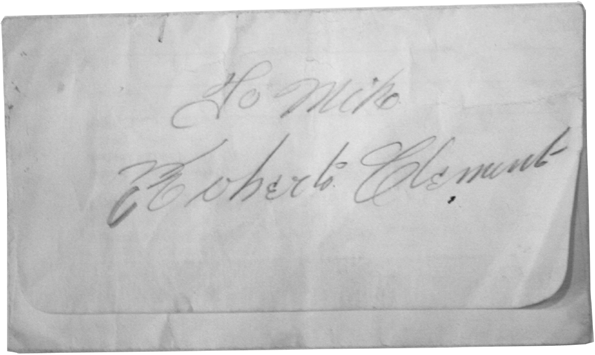

I still have something from that event that transports me instantly back in time. It’s an envelope. On the back is a request to donate to NEED, the Negro Emergency Education Drive, which, I have learned, has provided over $35 million in grant allocations to worthy African-American students in the Pittsburgh area since its inception in 1963. On the front there is this:

***

On the morning of January 1, 1973, I grabbed the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, took it up to my bedroom and, like every person in Pittsburgh and every baseball fan in the world, read in stunned disbelief that Roberto Clemente was missing in a plane crash on a humanitarian mission and believed to be dead.

***

Clemente was 38. He had been a transcendent player for a long time. He had gradually and in some quarters grudgingly become a hero and perhaps even a legend. A season earlier, in 1971, he became a god.

It had been a long hard road. The first great Latin American player and everything that came with it. The language barrier that never went away. The claim that he was a malingerer. The pride. Roberto Clemente was not without his imperfections. It would never be easy with him. I remember all of it, but from a small child’s perspective.

In the summer of 1971, Pittsburgh opened its heart to Roberto Clemente. For the country, it may not have been until the World Series that fall. For Pittsburgh, it was earlier. He had been beloved by many people in Pittsburgh for a long time, especially by children. But a number of things came together in 1971 that took the way Pittsburgh felt about him to a higher and more lasting place. Some involved him only indirectly. There was a new stadium with, however briefly, an exciting new feel to it, just as the Pirates, with their fancy new double-knit uniforms, were putting together their best team in a long time—and maybe their best team ever.

When Pittsburgh took another look at Clemente in 1971, it began to have a feeling that doesn’t happen much anymore, especially in places like Pittsburgh. The feeling a city develops for the baseball player who stays for his whole career. Ted Williams in Boston. Ernie Banks in Chicago. When it begins to realize that it better appreciate him now because it will not have him forever. I watched Clemente all that summer. After a broken arm changed my plans to be away at camp, I went to about 40 Pirate games in 1971. For me, the defining memory of how Pittsburgh felt about Roberto Clemente before he died was in what ended up as an 8-7 10-inning loss to the San Francisco Giants at Three Rivers Stadium on July 22, 1971.

It was a sunny Thursday afternoon. Clemente was getting a day off. The Bucs went into the ninth inning down 7-3 to Juan Marichal, which was not a good place to be. But after three singles and a walk it was 7-5. The Giants brought in Steve Hamilton to pitch.

To the sounds of “Jesus Christ Superstar,” which is what they played when he came to bat in 1971, and which itself tells you all you need to know, Roberto Clemente came up to pinch hit. He was greeted with a thunderous standing ovation from the crowd of 33,000. A moment later, when Clemente bounced a double over third to tie the game, there was another thunderous standing ovation. Jackie Hernandez came in to run for Clemente. As he came off the field, there was a yet another thunderous standing ovation.

It took far too long for some, but the people of Pittsburgh knew what they had in Roberto Clemente and they knew it before his plane went down and he was gone.

****

When Clemente came to the plate, he would twirl his neck in exaggerated circles to loosen up an old and severe injury. After he was settled in, which took a while, and found a pitch he liked, Clemente would uncoil and dive across the plate to drive the ball into right field. He was the complete player and the complete player would use the whole field. Nobody ever did this more explosively, more fearlessly or with more passion. Although he sometimes rocked back and wound up on an inside pitch to drive it to left, Clemente’s opposite field approach to hitting meant that he would not hit as many home runs. This is the one thing that the few holdouts cite to deny Roberto Clemente his place among the greatest of the great.

The way he attacked the strike zone also led, not infrequently, to one of the dramatic moments in baseball: Clemente escaping a brush back pitch. The batting helmet would come off, dirt would fly everywhere and, it seemed, Clemente would move in three directions at once. Then he would slowly pick himself up, dust himself off, adjust his batting helmet and give the pitcher the most serious and ominous look. I’m sure that Clemente did not lace one up the middle past the pitcher’s ear every single time this happened. I just remember it that way.

On the bases, Clemente ran with a wild, galloping style. When he arrived to beat a throw as he so often did, it was to a tremendous commotion. That style masked the fact that Clemente was a consummately intelligent base runner. The single into a double. The double into a triple, 85 of them after the age of 30.

He also was the greatest defensive right fielder who ever played baseball, about which there is no serious debate. If it was easy, it was the basket catch, same as the greatest centerfielder, Willie Mays, but with a Latin flair and a looping underhanded toss back to the infield. If it was hard, it was like watching a bird in flight. Everyone has a favorite Clemente catch. There was one in Houston that is mythological. For me, when I close my eyes, I see myself in the right field seats at Three Rivers Stadium with my father on July 18, 1971, looking down on Roberto Clemente as he flew into right center to make a diving backhanded grab to save the first game of a double-header sweep over the Dodgers, before Luke Walker took a no-hitter into the ninth in the second game.

And then there was The Arm.

Words can only take this so far. Do yourself a favor. Get a hold of some old tapes or online videos. Rockets to third base coming out of nowhere from the right field bullpen at Forbes Field. Behind the runner who took a wide turn at first. Or just to throw someone out at first on a sharp hit. In 50 years of watching baseball I have seen one throw by anybody else that I would call a Roberto Clemente throw, by Jose Guillen from the right field wall to third base one night in Colorado.

There are countless candidates, but, for me, there is one Clemente throw that stands above all others. It is odd that this throw is not better known because it prevented the winning run from scoring in the bottom of the ninth inning of one of the truly great World Series games, the sixth game of the 1971 World Series, won 3-2 by the Orioles in the tenth by Frank Robinson’s daring slide under the leaping Manny Sanguillen. Somehow this throw did not make the Clemente highlight reel so frequently shown from that World Series, perhaps because there is so much from which to choose.

With the score tied at two, and Mark Belanger on first, Don Buford hits one down the right field line to the wall. There are two outs and Belanger is running; Buford’s hit surely will win the game. Clemente sails over to the deepest corner, plays the carom perfectly in an unfamiliar stadium, grabs the ball, wheels and fires from the right field wall, 300 feet away. An instant later, it takes a short hop and hits Manny Sanguillen’s catcher’s mitt at home plate. Sangy does not move a muscle. Neither does Belanger at third. They showed this throw on the World Series highlight film at our camp the next summer. The Pittsburgh and Baltimore kids knew it was coming. Everyone else just gasped. I know that this is the greatest throw Roberto Clemente ever made because it is the greatest throw that anyone ever made.

Roberto Clemente also hit a home run and a triple in that sixth game. The next day he hit another home run, 400 feet to dead center, to break a scoreless tie in the taut and excruciating 2-1 seventh game win. It was his twelfth hit in a World Series in which he batted .414 and hit in every game, and in which he played right field and ran the bases in a way that the people who saw it will never forget, the way people in Pittsburgh had seen it for 17 years and I had seen it all that summer. Afterward, interviewed for television in the locker room, he put aside the praise that was being heaped upon him to thank his mother and father in Spanish. Roberto Clemente was an artist and the 1971 World Series was his masterpiece.

Life works in strange ways. I wasn’t even supposed to be in Pittsburgh that summer. It was only because I did a stupid kid thing and broke my arm. Fifty years later, it is one of the treasures of my life. In the summer of 1971, at the exact moment of his apotheosis, I watched the great Roberto Clemente play baseball.