Illustrated by Daniel Marsula

February 28, 2024

One night in Pittsburgh, in the middle of a Pirates game, Radio Rich, puffing on his pipe, came up to me in the press box and asked why the San Francisco Giants named their venue Candlestick Park.

“Because,” I said, “they built it on Candlestick Point.”

Radio looked askance. “Any other reasons?” he said.

His real name was Richard Glowczewski. Somebody once asked him his middle name. “It’s just Richard Glowczewski,” he said.

“You got one?”

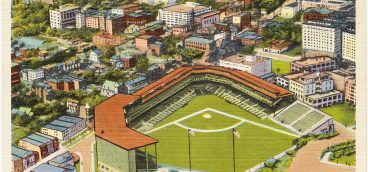

Radio Rich could be disarming, frustrating, infuriating, puzzling and pixelating, all at once. But everybody in Pittsburgh loved him, and without him, Bob Prince’s radio broadcasts of Pirates games would not have been nearly as informative. When the Pirates left musty old Forbes Field and moved into Three Rivers Stadium in 1970, my seat in the press box at the new place was far left in the front row. The only thing separating me from Prince’s booth was a large soundproof window. I could look to my left and see Radio (NMI) Rich bending over and whispering into Prince’s ear, which went on constantly during the course of a broadcast.

One night, when I skipped a game and was listening at home, Prince said: “Radio Rich says the Cardinals have loaded the bases in the bottom of the sixth. Rick Wise has been kayoed and the Phillies have gone to the bullpen.”

It was the pre-internet days. Radio wasn’t getting the news on a computer, or even from the slow-moving Western Union ticker in the back of the booth. With one of the countless transistors that grew out of his ear, he had picked up the Cardinals broadcast from St. Louis, and was feeding Prince the details in real time. During a pennant race, Pirates listeners couldn’t have been better informed.

Another night, Prince might say: “Radio Rich is telling us that Leo Durocher is out in Chicago. Whitey Lockman will be running the Cubs the rest of the way.” Or, “Radio Rich says they’re taking off the tarp in Atlanta. It looks like the Braves will be able to finish that game after all.”

When a game was over, before signing off, Prince would thank his engineer, his broadcast partner, Nellie King, and conclude by saying, “And thanks to Radio Rich, for all his updates.”

Newcomers to Pirates broadcasts might be saying: “Who the hell is this Radio Rich?”

He was part of that overflowing roster of Pittsburgh characters, torn from the pages of the Sunday funny papers: Beersie Gordon. Baldy Regan. Myron Cope. Myron O’Brisky. Chilly Doyle. Beano Cook. Diz Bellows. Hugo Iacovetti. Mooch O’Toole. Archie Litman. Hoolie Hallahan. Billy Conn. Elmer Goyer (who seemed to live in the lobby of the Carlton House, always greeting passersby with: “Never fear, Elmer is here!”). A horseplayer called “The Waterford Wizard.”

Some of them actually had real jobs, but many just seemed to loaf, which is a Pittsburgh term for living life on cruise control.

A major domo like Art Rooney, owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, reveled in their company and gave them uncommon access. In a sense, he was one of them. One day, Radio Rich sat in Rooney’s modest office, rehashing a recent Steelers defeat, in which the fourth-quarter play of their quarterback, Joe Gilliam, was roundly called into question.

“Too many second-guessers in this town,” Radio said in defense of Gilliam. “It burns me up.”

“Rich, it’s their right,” Rooney said.

“I still don’t like it,” Radio Rich said.

Richard Glowczewski was an orphan, once headed in the wrong direction. At 19, he was arrested for stealing a quarter off a newsstand kiosk, and possessing a transistor radio, a shirt and a pair of pants, all with the price tags still attached. He told police he lived at the Anderson Hotel, which had been torn down before he was born. In truth, he lived at the YMCA but was unemployed. A priest called Joe O’Toole, an executive with the Pirates, described Glowczewski as a sports fanatic with a startling memory for statistics and minutiae. He walked several miles to O’Toole’s office and got a hey-boy job that led to more work with virtually every team in town, professional and college. Before landing as publicist for the Steelers, Joe Gordon remembered working for the Pittsburgh Rens, a team with the short-lived American Basketball League. “Appearing out of nowhere was Radio Rich,” Gordon said. “It seemed like he came with the franchise.”

At a time when Prince was doing pro hockey, Radio took a bus to Baltimore to help him with a game. He had $10 left, not enough for a return trip to Pittsburgh. Prince gave him another $10, but by the time the game ended, he asked for the money back and somehow they got to the Baltimore airport, where Prince wrote a check for two seats to Pittsburgh. As the plane was about to land, Radio turned to Prince and said: “Don’t forget, you owe me 10 dollars.”

Radio had never been to a dentist, so Prince paid $700 to have all his teeth pulled and replaced with dentures costing another $300. Radio soon asked for an increase in the per-game fee that Prince paid him out of his own pocket. “With my new teeth, I can chew steak now,” he said.

Late in Prince’s long run with the Pirates, the commissioners of Allegheny County did him a testimonial, and from the dais he put them on the spot by asking that they give Radio Rich a job. He was hired, for $600 a month, as a clerk for the Parks Department.

After 28 seasons, Prince was fired at the end of 1975, to huge public outcry. His career stayed in flux after that, including a belated, ill-advised second act with the Pirates, and he died of cancer, at 68, in June of 1985. In June of 1986, cancer did in Radio Rich as well. He was 54.

“He was a giver, not a taker,” Joe Gordon of the Steelers said. “If you wanted something done, you could put it in the bank that it would be done. Too often we measure people on how far they ascend the ladder of success, without paying any attention to where they came from. Radio was a beautiful person and he never hurt anyone. How many people can come in and go out, and say they never hurt anyone?”