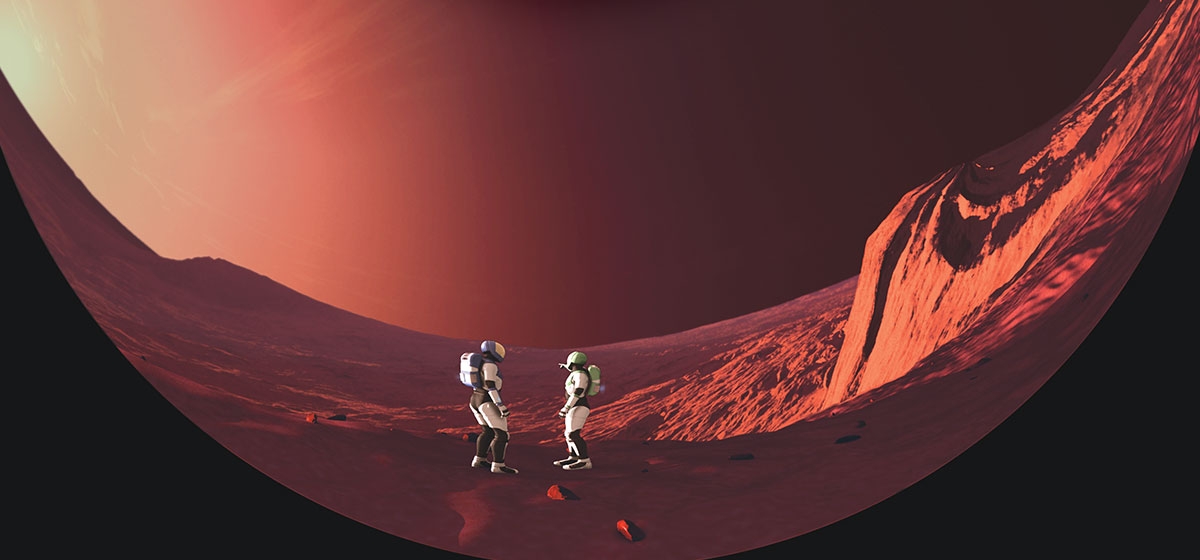

First the lights dim. In the darkness, you feel the intense drumbeat and techno-pop rhythms of the synthesizer pounding deep in your gut. Next a fiery, red globe materializes above you like a cosmic disco ball of galactic proportions. Look left and a futuristic spacecraft emerges from the solar system beyond. It begins to circle the shadowy planet, hurtling at warp speed through the thin, dusty atmosphere.

Moments later, the shuttle careens into the surface, in a violent landing that would unnerve the most intrepid of astronauts.

Welcome to Mars.

One by one, crew members exit the cockpit, stepping down with uncertainty onto the cold Martian terrain.

With the help of an iPhone-like navigation device, they begin their search for fossil evidence that life might have formed in the planet’s watery past. They explore polar ice caps and volcanoes, dry river beds and ancient craters, all painted in exquisite detail across the vast, digital canvas overhead. And you are along for the ride, without ever leaving the comfort of your chair inside the new Buhl Digital Dome.

The high-definition projection system, made by Sky-Skan, Inc. of Nashua, N.H., was installed in the fall of 2006 at the Carnegie Science Center through a $1 million grant from the Buhl Foundation.

This revolutionary “full-dome” system is spawning a new breed of planetarium where entertainment technology and science education find common ground.

It can take any digital picture or video—up to 16 million pixels a frame—and spread it across the Buhl’s 50-foot hemispheric dome, giving you a truly immersive experience as you explore faraway planets or the hidden recesses of the human body.

Two projectors, each outfitted with a fisheye lens, seamlessly blanket the dome with these ultra-high resolution images, extending them beyond your peripheral vision. This creates the jaw-dropping sensation of moving through three-dimensional space and time, making you a part of the scene as it unfolds.

“The planetarium is really a virtual reality chamber,” says Susan Reynolds Button, past president of the International Planetarium Society. “I don’t know of another venue where you can be completely immersed in the situation, place and time.”

But the new Buhl is more than a souped-up version of your favorite Cineplex. In the past decade, the planetarium also has become a full-scale production studio, where artists, writers, computer animators and scientists develop original programs seen each year by hundreds of thousands of people worldwide. “If you travel just about anywhere and pop into a planetarium show, you’ve got a pretty good chance that it might be one of ours,” says John Radzilowicz,director of visitor experience at the Carnegie Science Center.

Since 1991, the Buhl has distributed more than 450 programs to universities, museums, other planetariums and science centers in 21 countries on five continents. These shows have been translated into 18 languages, attracting luminaries such as Star Trek’s Leonard Nimoy, science fiction author Sir Arthur C. Clarke, Mark Hamill of Luke Skywalker fame and Fred Rogers.

This spring, it will debut its latest production, “Two Small Pieces of Glass,” which celebrates the 400th anniversary of the Galilean telescope in conjunction with a new PBS documentary.

“The Buhl is a world-class planetarium with a very big reputation of producing great things,” says Reynolds Button.

The added potential of the full-dome system could further up the ante. “We are already considered one of the major players, and this gives us an opportunity to move even closer to the top of the pack again,” Radzilowicz says. The creative force behind the Buhl’s success has been James Hughes, who more or less grew up inside the planetarium, back when it was called The Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science and was located in the North Side. The Buhl Foundation opened the doors of the institute in October 1939, as a testament to Federal Street merchant Henry Buhl Jr., who left $11 million in his will to establish the charitable trust that bears his name. It was the fifth major planetarium in the U.S., featuring a 492-seat “Theater of the Stars” with a 65-foot steel dome.

You would be hard pressed to find anyone in Pittsburgh over 25 without memories of the Zeiss Model II star projector. The 6,000-pound electro- mechanical behemoth rose like an apparition from the floor of the old Buhl to conjure up the heavens, becoming the stuff of childhood dreams—and probably a few nightmares.

Hughes, though, had a closer view than most other kids of this astronomical icon. His father, Roy Hughes, was a technician at Buhl for 31 years, while his aunt, Shirley Hughes, has worked in the gift shop for almost a half-century. The Shaler native began his first job at the planetarium in 1976 as a “star pilot,” operating the projector during the decade’s popular laser shows.

In doing so, he became too captivated by the majesty of the cosmos to leave.

“It is hard to work in a planetarium and not become enamored by the stars and the sky,” says Hughes, a part of the five-person production team at Buhl.

Traditional planetarium shows used only a Zeiss-like projector to display crisp, pinpoint images of the stars overhead, relying on a lecturer to guide audiences through the night sky. In the 1970s, planetariums began to scatter a bevy of slide, film and video projectors around their domes, along with mirrors, sound systems and other special effects to enhance their programming.

At Buhl, Hughes was put in charge of running this panoply of equipment. “We always said that Jim was like the conductor of an orchestra because he had like 100 pieces of machinery he had to blend together for a show,” Radzilowicz says. In 1982, the Buhl Planetarium became the Buhl Science Center and began plans to move to a location along the Ohio River just below where Heinz Field stands today. Five years later, it merged with Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, and in October 1991, The Henry Buhl Jr. Planetarium & Observatory opened in the new Carnegie Science Center.

Upon moving, the planetarium replaced the Zeiss machine with a digital star projector underwritten by the Buhl Foundation. For the first time, audiences could not only see stars, but fly through them in three dimensions. The digital system also projected dots and lines that appeared on the dome as wireframe models of comets, spacecraft and other objects.

Galvanized by this robust video technology, the Buhl decided to begin producing its own shows—a dream come true for Hughes. “It was really a matter of loving a chance to tell these stories,” he says.

Drawing upon his insider’s knowledge of the planetarium and lifelong interest in multimedia, Hughes set out to help create the Buhl’s first original show, “Venus: Earth’s Fiery Twin.” The debut was a success. Educators and schools loved the program, which quickly sold all 25 copies made.

Four years later, the Buhl produced its first blockbuster, “Through the Eyes of Hubble,” chronicling a repair mission to the space telescope. Narrated by Star Trek’s Gates McFadden, the show was licensed by NASA and the Space Telescope Science Institute and distributed to 150 planetariums.

Other hits soon followed, such as “The Search For Life In The Universe,” starring Nimoy, and “The New Cosmos,” with voiceovers by Clarke. A perennial favorite with the preschool set remains “The Sky Above Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.” Written and narrated by Fred Rogers in 2001, the show explores celestial wonders in a computer-animated adaptation of his children’s television show.

Along with probing the outer limits of the universe, the Buhl also began to transport audiences deep into the human body.

In 1995, the planetarium first aired “Journey Into The Living Cell,” produced with researchers at Carnegie Mellon University and funded by the National Science Foundation. This spectacular glimpse into how cells work was followed by “Tissue Engineering For Life,” a five-part series highlighting breakthroughs in regenerative medicine.

Duquesne University biology professor John Pollock, who directed these programs through a grant from the National Institutes of Health, says the planetarium is an ideal venue for illustrating the beauty of the microscopic world and teaching the hard science underlying this visual splendor.

“As a scientist, I have an insight into how things work and look in the body, and by collaborating with artists and animators on these shows, I can put that knowledge visually into the hands of the public,” says Pollock.

This rich, diverse programming quickly caught the attention of the planetarium industry and the public. The new Buhl began to draw more than 125,000 visitors each year, making it one of the biggest tourist attractions in Pittsburgh.

Hughes was invited to share his expertise at planetariums in China, Australia, and across Europe and the United States. And sale of Buhl shows started to provide a consistent revenue stream for the nonprofit science center.

Then came the advent of the full-dome revolution in the late 1990s.

As its name suggests, full-dome digital technology projects a computer graphics display onto the full surface of a dome.

Now planetariums can explore the cosmos as never before, zooming in on colorful, textured stars, drawing the trails of soaring comets and jumping to any moment in the history of time. Audiences can watch two galaxies collide over a billion years or simulate the formation of the universe in just seconds. They can leave Earth and observe the solar system from any vantage point, or leave the galaxy entirely to view the large-scale structure of the Milky Way and beyond.

Video footage can be made in advance—or pre-rendered—yet live star talks are still possible using a digital atlas of the universe to generate a map of the sky.

Gone are the days of scrambling in the dark to synchronize slide projectors, video, special effects and the star projector. Instead of slides, shows are recorded to MPG video files like DVDs. Simply fade the house lights, hit “play” and the stars come out.

“This is an amazing new world for planetariums,” says Reynolds Button.

Digital domes are quickly becoming their own industry, with more than 200 theaters worldwide, 15 equipment vendors and an equal number of show producers vying for market share, according to a 2006 survey published by digital dome pioneer Ed Lantz, who serves on the IPS full-dome video committee.

At least 40 full-dome science programs are available, with five or six new titles a year, Lantz estimates. The federal government gives millions of dollars each year to major science centers to create these shows. There are courses on immersive cinema, an active listserve, and Web sites devoted to full-dome discussions, and even full-dome film festivals with “Domie” awards for the best productions.

To remain competitive, the Buhl recognized it had to make the switch to full-dome, Radzilowicz says. One million dollars from the Buhl Foundation finally made the upgrade possible. The foundation wanted to ensure the world-class planetarium it founded 70 years ago would remain a leader in science education, says President Frederick W. Thieman.

“Stimulating young people’s interest in science and technology is key to developing a talented workforce in western Pennsylvania and to our mission,” Thieman says. “It’s hard to find a place that does the job better than the Digital Dome.”

The foundation grant purchased a full-dome system called Digital Sky 2 for the Buhl—a system with enough computing power to allow Hughes and his staff to work behind the scenes on new programs while screening an existing show for the public.

Their premier full-dome production, “A Traveler’s Guide To Mars,” was adapted from a book by planetary geologist and New Kensington native William K. Hartmann, through a $400,000 gift from the Bozzone Family Foundation.

The show was produced in conjunction with Home Run Pictures, a Downtown-based animation and special-effects studio that creates computer-generated imagery for topflight clients such as the Discovery Channel, National Geographic and PBS. It also is one of the few independent companies in the world generating content for full-dome theaters, says President and Creative Director Tom Casey.

Casey, a Beaver Falls native who studied engineering and graphic design, opened Home Run Pictures in 1991, when his wife refused to accompany him to Hollywood to hunt for a job. His first break came when he landed a gig to animate six “Titanic” programs for the Discovery Channel. Building underwater scenes for these highly rated documentaries posed a unique challenge, but it was a cakewalk compared with working in the full-dome medium, Casey says.

Creating a full-dome show follows the same basic process as making an animated movie such as “Toy Story” or “Ratatouille.” You write a script, develop the characters and storyboard, produce the scenes and then assemble and edit the show.

But watching a standard film is like gazing at a scene through a flat rectangular window. Part of what makes full-dome production so difficult is that viewers can look overhead in every direction at a screen that completely encircles them. “Pixar and Disney can ignore things that are outside the frame,” Casey says. “In our case, nothing ever leaves the frame.”

Casey and his team devised a method of gluing together five camera views of a scene to fill the circle of the full dome. These calculations take gigabytes of computer memory and often stump their graphics software designed for standard film production. A newer, less complicated approach places a fisheye lens on the camera inside the computer to capture the entire scene that will be projected on the dome.

Casey also had to find a way to suspend the disbelief of planetarium audiences during computer-generated scenes that can last for minutes, compared with just a few seconds in regular movies. “That’s like a lifetime,” Casey says. “So it’s a little more difficult to stylize things to the point where it looks believable.”

It can take anywhere from several minutes to hours to produce a single full-dome frame, and there were 36,000 frames in the 20-minute Mars show.

In the program, Home Run Pictures used real NASA elevation data and imagery to recreate the Martian terrain. Animated astronauts were brought to life with motion-capture techniques, with the help of Cranberry-based visual effects studio Cinemanix Productions. This technology uses 3-D facial and body movements recorded from actors to make the motion of animated characters more realistic.

The result is a Mars encounter in the immersive dome unlike anything you might experience with a telescope or robotic probe. Instead of just seeing images of the Red Planet, you feel as if you are stepping down onto its surface.

Casey recalls visiting the old Buhl as a child on school field trips. “The first show I saw was about Galileo, and I remember looking at how the stars moved and thinking that was the coolest thing I had ever seen,” he says.

“But it isn’t just star shows anymore,” Casey adds. “I think once people start going to the Buhl Digital Dome, it will change their ideas about planetariums and hopefully get them excited.”

That is what the Buhl is banking on.

Hughes and Radzilowicz began to generate industry buzz by screening the Mars show for 300 planetarium professionals who convened at the Buhl for a recent meeting of the Great Lakes Planetarium Association.

“Now the phone is ringing again,” Radzilowicz says.

It can cost upwards of $30,000 to license a full-dome show, but thanks to lower overhead costs in Pittsburgh, the Buhl hopes to attract more customers by selling the rights to its shows for about $10,000 apiece.

Future full-dome programs could explore advances in fields as diverse as nanotechnology, medicine and architecture. Already, Pollock’s team has produced a full-dome show called “Our Cells, Our Selves” about the human immune system.

In his shows, Hughes always tries to inspire visitors to the planetarium to reflect upon their relationship with the cosmos. “The fact that we can ponder the universe and learn about it makes it as much a part of us as we are a part of it,” he says. “I like to say that you are as unique and complicated as a galaxy.”

And whether that galaxy is generated by the classic star projector he knew so well as a child, or a state-of-the-art digital full-dome system, that sense of awe and wonder is one thing at Buhl that Hughes hopes will never change.