Pittsburgh’s Hardest Working Angel

Enter the warehouse and, if you aren’t bewildered by the seeming randomness of it all, you get a sense of the urgency. Mobile hospital beds. Crutches. Respirators. IV poles guarding bedpans. Hundreds of boxes of pharmaceuticals. Medical equipment bound for Nigeria, Uganda, Guyana. And for some reason, dozens of suitcases, many of them more than gently used, soaring on shelving to the top of the warehouse. The collection is so vast and riotous that you wonder for a moment if it’s been assembled by Lex Luthor, as if by cornering the market on life-saving stuff he could finally lure that pesky Superman from his Fortress of Solitude.

But there is method to this madness, and the purposes for it couldn’t be more noble. This is the North Side warehouse of Brother’s Brother Foundation (BBF), one of the world’s most effective and respected providers of humanitarian relief. All the supplies in the warehouse soon will be shipped to victims of disasters… and to those for whom deprivation is a daily circumstance.

On Sept. 30, BBF will celebrate its 60th anniversary with a gala at the Heinz History Center. There is much to celebrate. Since its founding, BBF has served 149 countries worldwide with over 106,000 tons of medicine, medical equipment and emergency supplies. In 2017, Forbes Magazine ranked BBF No. 66 on its list of America’s top charities by value of private support. Forbes noted that the foundation operates with 100 percent fundraising efficiency, that is, the percent of private donations remaining after deducting the costs of getting them, and is one of only 14 charities in the country with a rating of 99 percent or higher for charitable commitment, defined as how much of a charity’s total expense goes directly to the charitable purpose.

For all its effectiveness and impact as a relief agency, Brother’s Brother had a rather different objective in its early years. Then, it was the brainchild of a man who may have done more than any other human to wipe out the scourge of smallpox.

Enter the ‘Peace Gun’

His name was Dr. Robert Hingson, an Alabama native who, in the 1950s, headed the anesthesiology department at University Hospitals in Cleveland. A deeply religious man, he decided it was his duty to wage war on smallpox and other diseases that were killing and crippling children throughout the world’s less developed countries. This was no pipe dream, as Hingson brought several unique strengths to the task.

One was his Baptist faith, a value set shared by others who would join him on his missions, support them financially, or both. Another was his power of persuasion. Hingson was a fastidious type, seldom wearing anything but a white shirt and tie. But he also was a champion debater in high school; he had an uncanny ability to get people to buy into his vision.

“He was able to project both the idea—and himself as an individual for the idea,” says his son, Luke Hingson, now BBF president.

But perhaps his greatest asset was his ability to invent medical devices—and persuade others to manufacture them—that would make his seemingly quixotic mission possible. Other attempts at mass inoculation had run aground on the problems posed by syringes and needles. Says Tom Wentling, vice chairman of BBF’s board:

“How do you keep a glass syringe with a metal tip sterile in the bush? The answer is, you really can’t.”

Yet another difficulty with needles—they’re painful. Getting children and their families to trek from the world’s most remote villages for shots that will hurt is a challenge.

Hingson surmounted these obstacles by inventing a jet injector that used a piston to propel vaccine into and under the skin. No needles, no pain. As Hingson introduced the device in all corners of the world, grateful children and parents began to refer to it as the “Peace Gun,” a name that endured. Hingson also found that the Peace Gun was so effective he could dilute the medicine needed for reliable vaccination, a discovery that saved millions in the cost of drugs. This was no small thing, as Hingson more than once had to mortgage his house or reach into his own pocket to underwrite mission expenses.

In 1958, Hingson, accompanied by his wife Tobie and members of his team, set off on his conquest, bringing the Peace Gun to Liberia, Honduras, Nicaragua and many other nations in need. The sights, documented by Cyril E. Bryant in his book, “Operation Brother’s Brother,” were unprecedented. Children lined up for blocks for their vaccinations. Once a youngster reached an impromptu clinic, a member of Hingson’s team pumped smallpox vaccine into one arm while another team member Peace Gunned a tuberculosis/leprosy preventative into the other arm. Even as those two technicians worked, a third dropped a dose of Sabin polio vaccine on the child’s tongue.

The direct impact of this herculean effort was enormous, of course, but the indirect effect may have been even greater. Hingson’s success helped mobilize a number of organizations, persuading them that some of the world’s most serious diseases could be wiped out, or at least controlled. Among those groups was the United Nations World Health Organization, which took up the battle—and versions of the Peace Gun—with renewed vigor.

In 1980, WHO announced that smallpox had been eradicated. The smallpox campaign was massive, involving thousands of people, but Hingson’s proof-of-concept and pioneering Peace Gun were among the keys. BBF estimates that Hingson’s teams personally inoculated more than 12 million people.

Superman, indeed.

New Mission, New Leadership

His success notwithstanding, Hingson was working himself out of a job. Sparked by his efforts, most of the countries he assisted established more permanent vaccination and health facilities, making emergency waves of inoculation less necessary.

“In the beginning of the efforts of Brother’s Brother, there were not enough health clinics to do static immunizations,” Luke Hingson says. “So these temporary vaccination campaigns were very important. They’re less important today because everything is now static.”

When Robert Hingson moved to Pittsburgh in 1968 to head the Anesthesiology Department at Magee-Womens Hospital, Brother’s Brother began to take on its current shape. Rather than working from team members’ homes, it secured a headquarters facility, moving around quite a bit before settling into its current Northside digs.

It was also during these years that Luke Hingson joined BBF after briefly considering other careers following his graduation from Tufts University.

“I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do,” he recalls. “I didn’t have a job, and I had no clear plan. I was this available kid, so I worked with my father, thinking this would be a short-term stint. I didn’t know any better.”

That short-term stint, helping BBF provide relief to Hurricane Fifi-stricken Honduras in 1974, helped show Luke what he wanted to do. When he signed on, it assured continuity of leadership following Robert’s death in 1996.

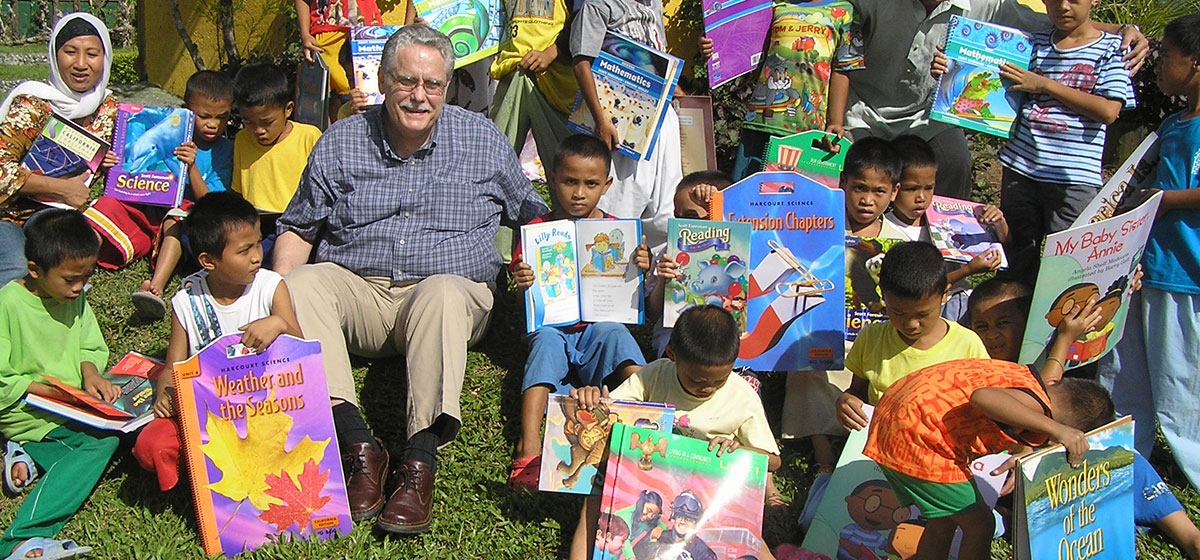

Perhaps most importantly in this period of evolution, BBF developed a new, multifaceted mission and a tagline—Connecting People’s Resources with People’s Needs—to reflect that mission. One thrust of the new-look BBF would be educational materials, chiefly books, that BBF now distributes throughout the world as primary textbooks or curriculum enrichment. The foundation has shipped more than 101 million books internationally and is considered the world’s largest distributor of privately donated books.

This is more complicated than it seems. English-language books won’t do much good in nations where English isn’t the primary language. In addition, publishers that provide BBF with excess or discontinued books aren’t necessarily selective with titles.

“We were offered a book many years ago about how to drive in the state of Montana,” Luke Hingson recalls. “This was about the time they had changed the speed limits there. This may be very important in the state of Montana, but if you’re in another country, not as much.”

BBF also started providing seeds to help hungry nations grow their own food. Between 1976 and 2000 the foundation donated a total of 7,742 tons of seed.

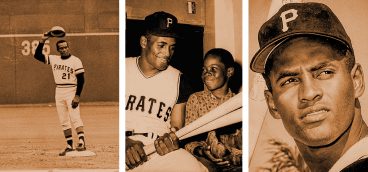

But the foundation’s best-known goal, by far, became providing relief to natural disaster victims. The initial response was to a 1970 earthquake in Peru. But it was the next relief effort, for earthquake victims in Nicaragua in late 1972, that helped change the equation. Robert Hingson already had reached Nicaragua with medicine and supplies when the world received the horrible news: Pittsburgh Pirates superstar Roberto Clemente had died in a plane crash en route to the Nicaragua relief effort. The coverage of Clemente’s death helped shine a spotlight on BBF’s efforts; the foundation’s relief component took off from there.

In recent years, BBF has stepped up after earthquakes in Mexico and Nepal and hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria. Here’s the way a relief effort typically works:

Once Brother’s Brother is asked to assist, it gathers needed materials from its warehouse; since that usually won’t be enough, BBF solicits in-kind donations. Many of the region’s hospitals maintain BBF collection bins for excess equipment and supplies such as gowns, masks and syringes. Pharmaceutical companies contribute most of the medicine. Explains Wentling:

“As the expiration date [for the drugs] nears, they think, hey, let’s offload this before the expiration date goes to zero and we can’t sell it. So there we are—sure, we’ll take it. They get a tax deduction, and we give it to people in need all over the world.”

When the disaster is abroad, BBF deals with appropriate government officials, often the ministry of health, to set up a formal distribution apparatus. Often, those officials at some point in their careers have trained or worked in Pittsburgh’s medical community, so a vital connection already may exist.

Then, BBF taps its volunteer mission doctors to travel in-country to supervise distribution. Remember those battered suitcases stored inexplicably in the warehouse? Mission docs stuff them with medicine and supplies for the trip.

But it isn’t only mission docs who’ll be going in-country. BBF often is assisted by crack volunteer units, such as Team Rubicon, whose sole goal is to provide hands-on disaster relief.

“They’re all former Special Forces or specially trained guys who will carry in everything they need,” says Sarah Boal, BBF’s director of medical missions and organizational initiatives. “They pick up the phone and call us and say, we’re going in.”

That’s the template, but in disasters, things seldom go as planned. In Nepal, for example, earthquakes had virtually wiped out the transport system, making the most remote villages inaccessible by normal means.

“One choice was to walk there—it might take six days,” Luke Hingson says. “The other was to take advantage of the tourist helicopter, as expensive as that was, and say, how about we show up in two hours?”

BBF commissioned the chopper, at a cost of about $50,000, and the mission continued.

Continuing the Legacy

BBF is much more financially stable than it was when Robert Hingson felt compelled to foot some of the bills himself. As Wentling notes:

“Our balance sheet has gone from a train wreck to $7 million net assets, which for us is unheard of.”

For all that, BBF expects to continue its evolution over the next few years. As more and more literary works are digitized, fewer books are available to BBF for distribution. Inevitably, this component of BBF’s services will diminish.

Another current trend, social media, also has affected BBF by providing immediate worldwide news of disasters. The impact, though, is uneven.

“You have the ability of instant explanation of a problem,” Luke Hingson says. “But one of the challenges we have with disasters is, because of the nature of the media and American interest, you can get a lot of money for one thing and hardly any for something else. But it doesn’t mean the people on the other end are hurting any less.”

As an alternative to that mad scramble for donations for disasters that don’t spark extensive media coverage, BBF is working with local foundations to establish a fund that can be tapped for immediate, unforeseen needs, such as that $50,000 helicopter rental in Nepal.

Finally, the organization is assembling a cadre of younger managers, imbued with BBF’s spirit, who can provide a smooth succession when Luke Hingson is ready to pass the torch. Says Boal:

“We’ve been working over the last couple years to strengthen our systems so we’re more ready to respond, so that when Luke can’t be with us anymore, we know how he would have made decisions and that we are continuing the family’s legacy.”

Building a team for Hurricane Maria relief

When Brother’s Brother participated in a fall 2017 relief effort to aid victims of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, it was a textbook example of a community pulling together to help after a major disaster.

With their deep ties to Puerto Rico through Roberto Clemente and other players over the years, the Pittsburgh Pirates appealed to fans to bring relief supplies to PNC Park. This they did, in droves. But how would all that material be shipped? The Pirates reached out to FedEx, which provided a plane.

“When we started this and found out FedEx was going to donate a plane, we were concerned that we wouldn’t have enough to fill it,” says Patty Paytas Salerno, senior vice president, community and public affairs, for the Pirates. “We were so fortunate with the response we got here that we needed a second plane.”

The Pirates paid for that second plane as well as subsequent shipments by sea.

Donated material needed to be sorted, packed and, perhaps most importantly, supplemented with medicine and medical equipment. BBF came aboard for that, working closely with the local Pittsburgh Metropolitan Area Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. Moreover, BBF energized the local hospital community—including volunteers from both UMPC and Allegheny Health Network—to pitch in.

BBF relief efforts often are facilitated by a key in-country contact. In this case, the link was Pirates coach Joey Cora, who connected the foundation with a large manufacturer in Puerto Rico. When that company agreed to participate, BBF had a ready-made distribution and transport network for 360,000 pounds of material, including medical supplies delivered to 17 hospitals.

Pirates to FedEx to Brother’s Brother. It may not roll off the tongue like Tinker to Evers to Evers to Chance, but it was an effectuve double play combination nonetheless.