Photo as Fact?

Living through the COVID-19 pandemic will become another watershed moment in our lives, and we will be asking “Where were you when…” for years to come. I remember what I was doing when the planes hit the twin towers on 9/11, but the event that rocked my world was the assassination of JFK.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”371″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]I might have been too young to think about how history of that moment would be written, but because contemporary artists have explored the construction of history, I am acutely aware of the process now. In this context, the current exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art, “An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain,” is particularly germane, even more so for people like me who grew up in the 1960s.

Lê, a Vietnamese/American photographer looks at the representation of war, starting with Vietnam. She applies personal and theoretical filters to her documentary-like images, mixing heritage, experience, memory and revision in her version of history. The resulting images, mostly in black and white, are large in scale and ideas. Her works allow you to wander through a familiar-looking landscape, searching for clues to a story or event as you wonder if there is more than meets the eye. Unfortunately, the only way to view this exhibition of about 100 photographs is through a virtual tour on the museum’s website, but the journey is well worth the effort. We can only hope that the Carnegie decides to keep the show up for a longer period so that we can see these images in person.

An-My Lê exploits the contested territory between fact and fiction as she searches for a way to process the Vietnam War. She goes beyond statistics and timelines to create more subjective views. Like many other contemporary artists, she deconstructs the idea we have that photography is the medium of truth. She uses straight photography, collected into series like the journalistic essays of W. Eugene Smith about Albert Schweitzer’s work in Africa or an American country doctor or the city of Pittsburgh. These projects were gathered in a show that came to the Carnegie in 1987. The idea that images can be manipulated and do not represent an unadulterated truth, an established trope in contemporary art, has now infiltrated the larger world, especially in the current debate about real and fake news. Lê has used this conceptual argument about photography in order to understand her own background.

The artist, born in Saigon in 1960, lived the war until her family left in 1968, the year of the Tet Offensive; from then until she returned as an artist in 1994, she was exposed to America’s viewpoint, leaving her with a conflicted understanding. When she returned to Vietnam (on several trips between 1994 and 1998), she started by photographing her country, producing black and white images that range from a moody view of Ba Vi National Park to a lazy waterway in Ho Chi Minh City with billboards (advertising Sanyo and Hitachi) along the bank. This series, especially in comparison with later work, can be seen as a cross between photojournalism from old Life magazines and a travelogue in National Geographic. In it, she set her operating principles: the use of a large-format camera and an elevated and distanced view.

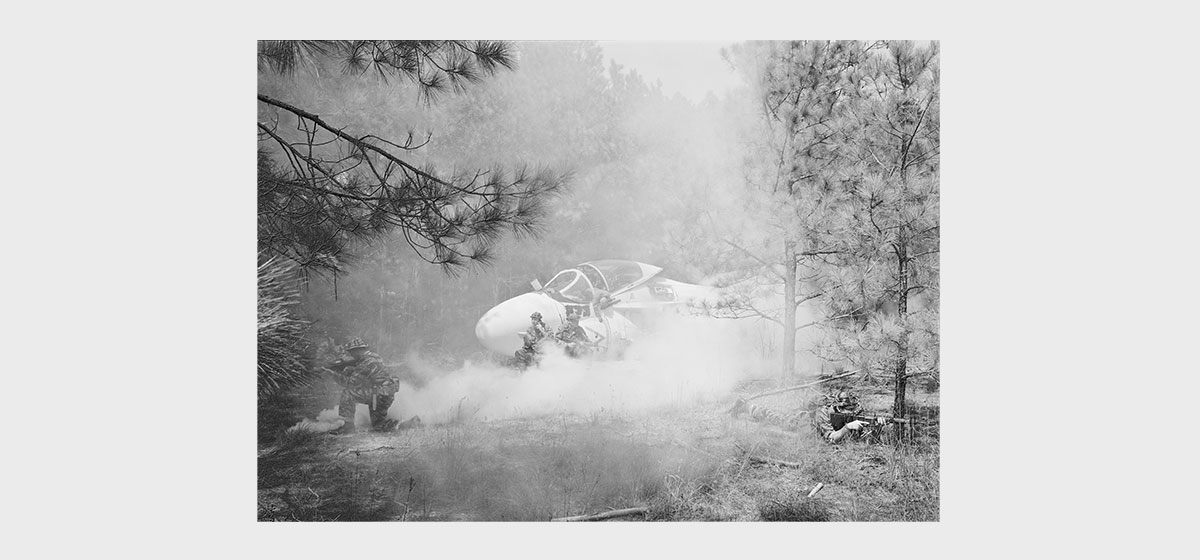

Only a year later, she was working on “Small Wars,” a series shot in Virginia and North Carolina during Vietnam re-enactments. Here she became both director and participant in an activity that merges fact and fiction, documenting activities that “re-enactors and living historians” stage to “breathe life into history.” Both educational and entertaining, these popular events add another layer to the process of constructing history; taking place in the South connects them to civil war re-enactments, and, in fact, Lê researched photographs taken during that war by Timothy O’Sullivan. Research has proven that some of the most popular civil war images taken by his contemporary, Mathew Brady, were staged as the photographer arranged bodies to make more powerful images. In Lê’s work, scenes of a downed plane, with the photographer herself hanging out of the cockpit, or a mortar explosion that looks like someone set off a firecracker, take place miles away from Vietnam and remind us that this was the first war that played out on television sets. Lê’s images follow those of conceptual artist Martha Rosler. In a series of collages (“House Beautiful, Bringing the War Home,” c 1967–72), she used photos from magazines, placing war images in picture windows or picture frames in contemporary home interiors to underscore our mediated experience of Vietnam.

Rosler and Lê, separated by three decades, both appreciate that our understanding of such significant events comes from sources that are more or less accurate. This mix plays out in a third series, “29 Palms,” shot in the desert just outside of Palm Springs. It was the site of American war games in preparation for war in Iraq. The terrain resembled the target’s homeland, and the military faithfully recreated villages and buildings for their training exercises. An-My Lê once again photographed from an elevated distance, which enhanced the theatrical sense. The tanks and buildings seem so small, like toy props, and our view simulates that of one from the balcony of a theater. The photographer also looked at the mundane activities of war, showing what happens between the actions. Lê started with an imagined present to get to a real past in what have been called “autobiographical still-lifes.”

Lê has continued to work in series and has begun to use color photography to capture aircraft carriers, contested Confederate statues, and even Antarctica. Her work depends upon envisioning contradictions as in the beautiful landscapes recovering from the war in Vietnam or ESL classes aboard an aircraft carrier or the contested importance of art about Confederate soldiers. She combines the personal and the political, hinting at aspects of war missing in our historical accounts. She adds a body of work that can be grouped with other sources of our knowledge about her subjects. The Vietnam War generated so many documents, but it also became the basis for movies ranging from “Good Morning Vietnam” to “Apocalypse Now” and the brutal documentary “Hearts and Minds” as well as novels such as the popular “The Sympathizer” by Viet Thanh Nguyen, an author whose conversation with the photographer is part of the catalogue for this exhibition.

The volume of material in so many different formats begs the question of how, and if, we can ever know what really happened in Vietnam. Hopefully Lê’s photographs can encourage people to expand their focus when looking at events like this political action/war. Artists have been deconstructing realism for a long time, and Lê’s work should be seen in that context. Carrie Mae Weems, a photographer who has investigated race in America, has been staging re-enactments of historical moments, gathered in a video entitled “Constructing History: A Requiem to Mark the Moment,” 2008. Based on research done by students, the process becomes part of the work as she weaves together the assassinations of Martin Luther King and JFK with elements of Vietnam and other pivotal moments.

The act of staging also characterizes the photoworks of Jeff Wall, the first artist featured in the Forum Gallery at the Carnegie. “Trân Dúc Ván,” his work from 1988 in the museum’s collection, is like a movie or stage still from a story of immigration and the homeless. In a related approach, Christian Boltanski created a pseudo-archive of the “International,” complete with mistakes, for the 1991 exhibition; Warren Neidich made large, color photographs of Camp OJ, the newscasters’ mini-city erected during his trial, documenting the birth of infotainment; Sophie Calle created false personal narratives under the guise of documentary images that she slipped into the decorative arts galleries in the 1991 “International.” More recently, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, included in the 2018 “International,” painted portraits that seemed to be real people that actually came from her imagination. All of this work makes us think about what we believe and what we think we know, and how we each individually and collectively construct a reality, a way of making sense of our world.

Some artists come at these conundrums face on while other arrive “at a slant” as Emily Dickinson writes when she declares that sometimes the truth is too difficult to bear. An-My Lê’s photographs deserve a prominent place in that continuum as she attempts to come to terms with the “undealt with.” My only regret is that so few people will see her work in Pittsburgh due to the pandemic because this is one of the most important shows the Carnegie has organized. Curator of Photography Dan Leers’ presentation, in the show and in the catalogue, is succinct and pithy, and like conceptual contemporary artists like An-My Lê, he raises as many questions as possible answers.