Norris Beach: “Swim Where You Will Be Welcomed”

Ninety years ago, on August 14, 1931, the city of Pittsburgh opened its largest and most luxurious public swimming pool in Highland Park. Opening day was one of great fanfare and pride. However, it was also a day that saw African Americans who tried to enter the pool turned away. When Black citizens returned the next day, the Pittsburgh Courier reported, four were beaten “by a gang of white hoodlums and driven from the pool.”

Similar problems would exist for many years, with Blacks finding no relief — either from Pittsburgh leaders or the courts — until a couple of Hill District entertainment and gambling entrepreneurs turned their sights beyond the city limits. Specifically, Gus Greenlee and Richard Gauffney turned to an unusually enterprising Washington County native by the name of Ruben “Rube” Wasler Jr. to find a solution.

Born in 1891, Wasler was 22 when his father died in a 1913 coal mining accident. Wasler enlisted in the army during World War I. Stationed at Fort Lee, Va., he was dubbed the camp’s “Irving Berlin” by an army newspaper because of his songwriting and singing skills. He cut his entrepreneurial teeth organizing a band and promoting shows on the base. Family members remember Wasler as a tall, outgoing, cigar-smoking man who was so bowlegged that a dog could walk between his legs when he was standing up straight.

Back in Washington after the war, Wasler began promoting Black auto races at Arden Downs, a dirt track north of town. His racing partners included Greenlee and jazz musician Jelly Roll Morton. The Arden Downs races made history in 1929 when Wasler booked the nation’s first interracial auto race.

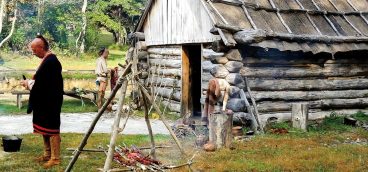

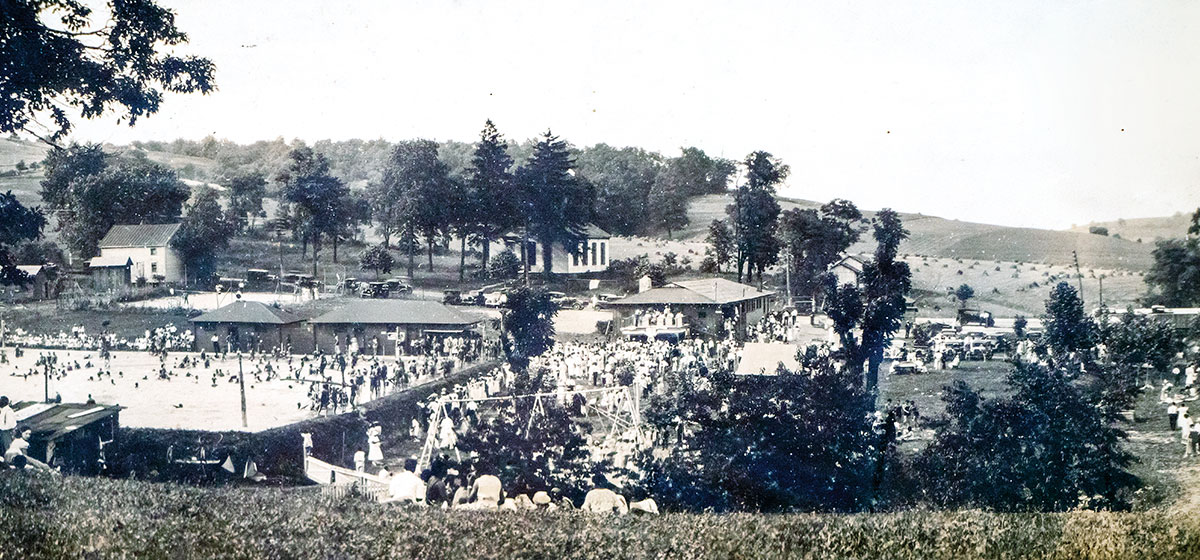

When Greenlee and Gauffney became aware of the problems at the Highland Park pool, they turned to Wasler. Together they set up the Tri-State Amusement Co., with Wasler’s downtown Washington red brick home as its headquarters. And in 1934, Tri-State leased a resort beach on the National Pike (now U.S. 40) about six miles east of Washington in the small, unincorporated community of Glyde. Glyde Beach Park was more than a decade old and was one of more than a dozen swimming beaches that developed outside of Pittsburgh in the 1920s. Before the 1934 summer season, Glyde Beach’s Canonsburg owners catered to white patrons.

Wasler’s Decoration Day (Memorial Day) grand opening promised something different: band concerts, a dance pavilion, tourist cottages, a tennis court, picnic grounds and a 750,000-gallon pool that could accommodate 5,000 people. And for Pittsburgh’s Black residents, traumatized by the Highland Park Pool violence, Wasler promised visitors could “swim where you will be welcomed.”

Glyde was likely an unusual place for a Black summer resort. The small crossroads community isn’t known for its ethnic diversity. “It’s been rural, white folks forever,” said one man whose family had farmed the area for more than a century and asked to remain anonymous. “I can’t imagine that there would have ever been African Americans that felt comfortable going to that community.”

But go they did. For the two years that Wasler rented the property, it was known as Norris Beach for the name of its owners. It hosted touring bands, church picnics and throngs of members of the Black Pittsburgh social club, FROGS (Friendly Rivalry Often Generates Success), and their guests during the fraternal group’s annual summer meetings. Surviving photos show the property’s three acres filled with hundreds of people and rows of parked cars. The Courier reported on the concerts, picnics, swimsuit contests and emancipation celebrations.

For the 1936 season, however, the pool reopened under new management and new policies. Ads in Washington County newspapers read that the pool had been “completely remodeled, sterilized and purified.” If there was any question about who might be welcome that season, other ads noted, “Caucasian Patronage Desired.”

The years rolled on, and after new owners bought the property in the 1950s, they eventually filled in the pool. They opened a motel there, across the highway from the Davison United Methodist Church.

Also gone, in that part of Washington County, is the memory that a happening swimming and events club that catered to the region’s Black population ever existed there. People who remember the pool don’t recall seeing African Americans. One, 79-year-old Ray Jennings, has lived in Washington County his entire life, and in the 1940s his family rented a farmhouse across the street from the pool. Neither he nor his 93-year-old aunt, who recalled attending a dance there, remembered seeing African Americans.

Published histories allude to the pool ultimately closing because of segregation issues, but that would have been long after Wasler’s time there. “A number of our readers … agreed that the end of the club, or at least its swimming pool, was the result of racial prejudice,” the Washington Observer-Reporter wrote in 2014.

Bob Jones has owned the property since 2006. It’s been used as apartments since the 1970s, he thinks. Once, however, he met someone who recalled the old pool and its days as a Black gathering spot. “I had a lady that lived in the trailer here where I’m at now that said she would skip school in Washington and come out with the Black people and swim when there was a swimming pool.”

As for Wasler, he got out of the entertainment business in 1939 and joined Washington’s police force, becoming one of the first Black officers in the previously segregated force.

“I remember my parents talking about him being one of the first Black police officers,” said Lorraine Perry, a retired Pittsburgh schoolteacher and administrator. “When I remember Mr. Rube, he was already an old man. And I just remember him walking on two canes.”

Wasler died in 1969 at the age of 78. His family still lives in the red brick house where all those plans were made a long time ago.