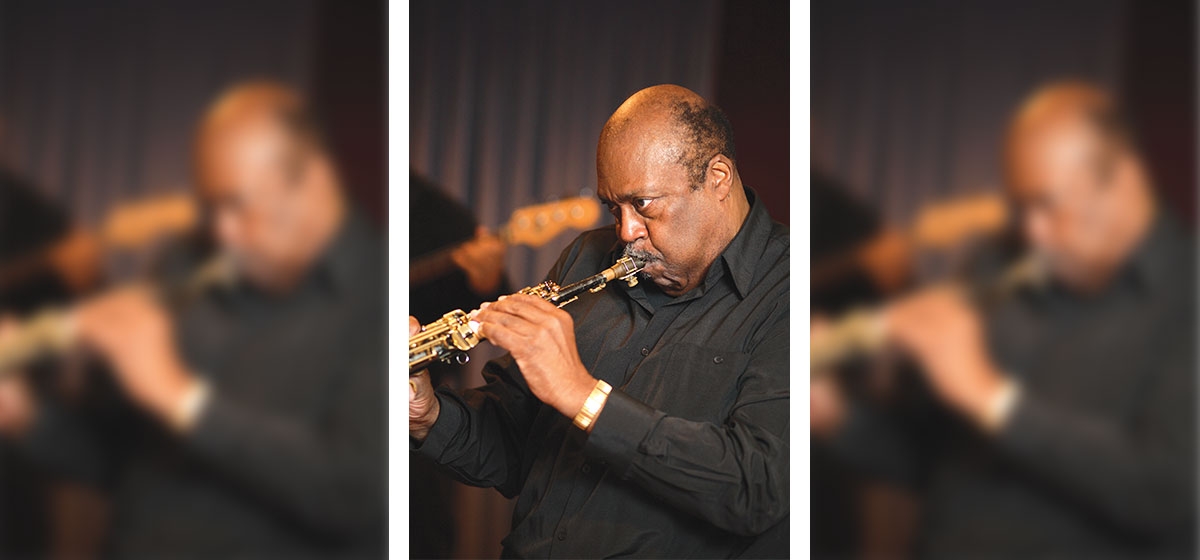

Nathan Davis, Music Educator, Performer, Composer

Kansas City, Kansas, and Kansas City, Missouri, are twin cities, with nightclubs and great musicians in both places. The only thing that separates the two cities is a bridge.

I grew up playing saxophone in Kansas City, Kansas, and went to the University of Kansas as a music education major. One night, a friend and I won first prize in an amateur contest at a club called the Orchid Room—50 dollars— which we split. I took my half, bought a bus ticket, went home and said, “Mama, I’m goin’ to Chicago.” After she stopped crying, she phoned my aunt, whom we called “Big Mama.” She was a big lady—something like 6 feet tall, 300 pounds—and a self-ordained Pentecostal minister! I had to stay with her when I went to Chicago.

Big Mama let me go play in the clubs at night because that’s what I wanted to do. That’s why I went there. But when I’d come home early in the morning after hanging out and playing in the clubs until dawn, she’d jingle her tambourine and say, “Lord have mercy, here comes Nathan! He’s been playin’ for the devil all night. Now he’s gotta come down and play for the Lord. Get down here boy!” (Both the church and her home were in the same building, which she owned.) So I’d get myself down there and join in with the sisters. It was really something.

My mother and father were separated when I was born — they later divorced — and I stayed primarily with my mother, who was a singer. When I started playing the saxophone, I started traveling with her. We’d go to churches and tea parlors and do mostly religious songs, like “Precious Lord.” Later, I began to play more popular songs like “Deep Purple” and a couple of others during our performances together. Back then, I also had this visitation thing with my father, who was a big jazz fan. He had every record of Jazz at the Philharmonic that Norman Granz ever produced, and he used to tell me about all the great players. I learned a lot from him. He helped deepen my love for jazz.

After college, I went into the military. I was in the 298th Army band stationed in Berlin, Germany, and we’d go around entertaining the troops. During that time, the great sax player Joe Henderson, who was also in the Army, visited Berlin, and we became best of friends. One night, Joe and I were hanging out, playing and talking, and the question came up: “When you get out of the Army, what are you gonna do?” We both agreed that we would like to live in Paris, study music with Nadia Boulanger, and play at night in the Blue Note with Kenny Clarke, the great drummer from Pittsburgh. That was our dream. But when I got out of the service, I stayed on in Berlin to play the local clubs, mainly because it was steady work. The truth is, it was at this time that I decided that I really wanted to work as a musician, not as a schoolteacher.

In Berlin, I worked with guys like trumpeter Benny Bailey and Joe Harris, another great drummer from Pittsburgh. Then a cat named Joachim Berendt produced and recorded a concert called Expatriate Americans in Europe. I was asked to substitute for the great tenor saxophonist Lucky Thompson, who couldn’t make it due to illness. Kenny Clarke heard me and invited me to join him in Paris at the famous club St. Germain des Pres! It was amazing. I went to work in one of the top jazz clubs in the world. One night, Dizzy Gillespie would come in. Another night, it would be Miles Davis, or Dexter Gordon, or Johnny Griffin and Sonny Criss, Carmen McCrae, or Nancy Wilson and Erroll Garner, another Pittsburgher. Everybody was coming to hear Kenny Clarke play. I was working seven nights a week, and started thinking, If I go back to the States, I ain’t gonna be workin’ seven nights a week, that’s for sure; and I’ll never have a chance to play with cats like Dizzy, Miles or Dexter. So I ended up staying in Europe for almost 10 years, about seven of those in Paris.

Now, how is it that I got to Pittsburgh? In 1969, I was still working in Paris, and planning on living and dying there. Around that time, the University of Pittsburgh had decided they wanted to add jazz to their music program. People started to get into jazz as a cultural thing. It was happening all over. Between 1966 and 1968, I taught a jazz history course at the Paris American Academy, which was founded by another Pittsburgher named Richard Roy. Bob Snow, chairman of the music department at Pitt at that time, contacted David Baker at Indiana University in Bloomington, and David recommended that they try to see if I would accept a new position at Pitt. It was Richard Roy and David Baker who negotiated that agreement for me to come back to the States. Most of the musicians I knew — Arthur Taylor, Johnny Griffin, Clifford Jordan, and so on — were against me returning. But not Kenny Clarke. He said that, when he was a kid growing up in Pittsburgh, there were few (if any) blacks teaching at the University of Pittsburgh. His advice was to take the job, and go and tell the truth about this great music.

Pitt was interested in me I guess because I had a degree in music education. But most jazz musicians at the time were skeptical of institutions that wanted to offer degrees in jazz. They thought, How can any school offer a degree in jazz? You can’t teach it. It’s a club thing. You just have to do it. David Baker, Donald Byrd and me — we were the pioneers of this whole business, the first to create full-curriculum jazz studies programs in the U.S., and the world. Everybody else came later. We often talked about the differences between musicians who came up through the clubs and musicians who learned in school. When you hear a club-wise player and then you hear one of these polished guys just out of school, you hear two different things. I think David saw me as a unique combination. I was a club-wise jazz musician who also had a degree. I could bring both the streetwise approach to improvisation and the academic structure necessary for a successful jazz program. So you see, I didn’t seek out a job at Pitt or any other university. Pitt found me in Paris. And I am eternally grateful because I have really enjoyed working at Pitt.

The University of Pittsburgh Jazz Seminar, which just finished its 36th year last fall, came about the way a lot of great things do—by accident. I was in Pittsburgh in 1969 trying to get Pitt’s jazz studies program off the ground, and I noticed that Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers were playing at the Crawford Grill. I had toured with them in ’65, so Art knew who I was. [The New Jazz Messengers then were: Art Blakey—drums, Reginald Workman—bass, Jackie Byard—piano, Freddie Hubbard—trumpet, and Nathan Davis—saxophone]. Word got out that I was in town, so Art called and said, “Come on down and bring your horn.” That night, I went and played with those cats. Art was so proud that he got up and said, “This man here is Nathan Davis, my ex-tenor player. I taught him everything he knows. He runs the music department up at Pitt.” And I said, “Art, I don’t run the music department. I’m just teachin’ jazz there.” But he went on. “Nathan’s my boy and I want y’all to support him.” Now, I was new in town, and that was one hell of an endorsement. Then for some reason, I asked Art if he would like to come up and talk to my students. He said, “Hey fellas, let’s go up to Pitt and help Nathan get goin’.” That’s how it happened.

I remember one year I really wanted Dizzy to come, and he had a gig somewhere out of town on the night we needed him. But he flew in anyway and did our seminar with his own money and didn’t charge us anything. Word started to spread, like I had some kind of magic touch, bringing in such amazing people. But there’s no magic, I can tell you. I once read in one of those European books, like an encyclopedia of jazz history or whatever, and it said something like, “Nathan Davis went to Pitt and put Pitt on the map by calling on his expatriate friends from Europe.” That’s exactly what I did. People that I knew passed the word around and we always got great artists to talk and play at our seminar. In the beginning, we were paying them no more than 500 bucks. Can you imagine that? Things have changed since then. Now I have supporters like Mellon Bank, Dominion, Office of the Provost, The Ford Foundation, and private donors like Larry Werner who contribute on a regular basis. As a result, we have been able to expand the outreach part of our program by taking it international. We were selected by UNESCO’s International Music Council to be the first and only jazz group to celebrate International Music Day throughout the world in such places as Bahia, Brazil, Jordan (The Queen Noor Conservatory of Music), the University of Ghana, Bahrain, and elsewhere.

When I look back on everything, the main highlights of my career at Pitt have been the excitement of bringing many great artists from around the world to Pittsburgh and the Pitt Jazz Seminar, and being part of the first university in the world to establish an International Jazz Hall of Fame. (Scholars, critics, and musicians from 20 different countries vote on who gets inducted.) And then, of course, there was the premiere of my opera called “Just Above My Head.” I sincerely believe that Mildred Posvar and Jonathan Eaton of the Opera Theater of Pittsburgh should be commended (and supported) for their enormous courage in presenting this minority opera to the City of Pittsburgh.