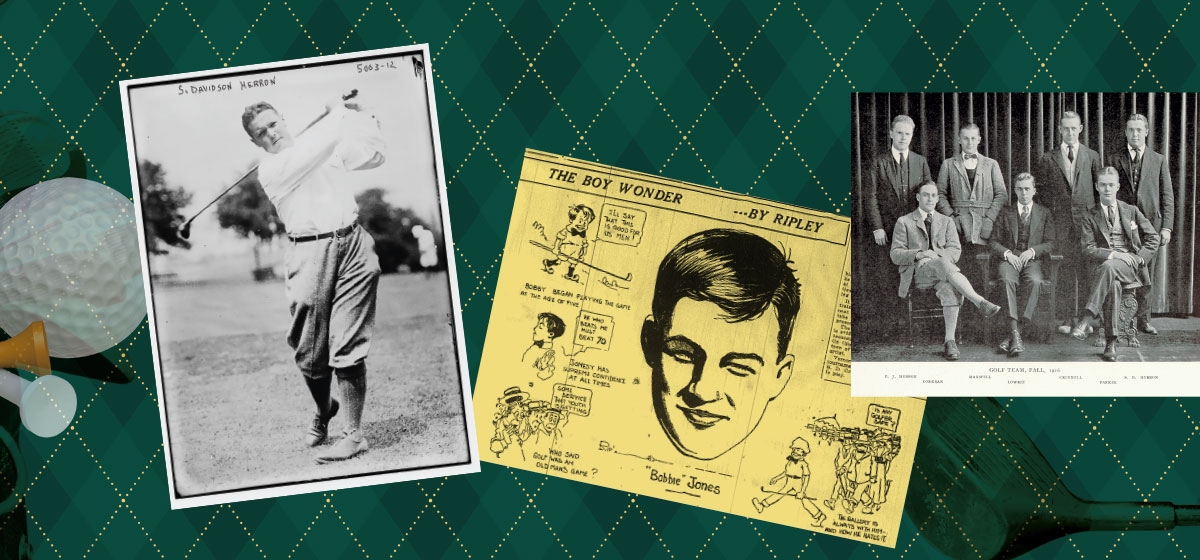

One hundred years ago, Pittsburgh native son S. Davidson Herron defied expectations that rising young superstar Bobby Jones was too much for him and won the prestigious National Amateur championship at Oakmont Country Club, shocking the golf world in the process.

The 1919 National Amateur was the first since 1916 due to World War I. And Dave Herron’s victory was remarkable. He conquered Oakmont, already arguably America’s most difficult course. And he defeated the 17-year-old Jones, golf’s “boy wonder” from Georgia and the most talented teen golfer the world had ever known.

While World War I raged in Europe, Jones had competed on equal terms against the sport’s top professionals, as well as its top amateurs. Most sportswriters and other experts following golf—those outside Pittsburgh, that is—assumed he would defeat Herron with ease.

But, as many in the Pittsburgh Press predicted, it was Herron who defeated Jones with relative ease, turning in a ball-striking and putting performance that marked a new highpoint in the 23-year history of the National Amateur. “Herron’s play throughout the tournament stamps him as one of the leading players of the country,” Joe Davis of the Chicago Tribune wrote.

Not everyone agreed. Golf historians generally have accorded Herron some respect, but many dismissed his victory at Oakmont as a fluke. It’s almost as if his triumph had to be explained away in order to validate the game’s greatest heroes, like Bobby Jones. Herbert Warren Wind, perhaps America’s most accomplished golf writer, saw Herron as merely “a competent golfer” and ignored his command of all parts of the 1919 Amateur. For Wind, the story was about why Jones lost, not why Herron won: Jones succumbed to his adolescent temper, losing the match on the 30th hole when he freaked out after a loud noise disrupted his swing and hit his ball into a difficult lie in a cross-bunker. “Jones not only mis-hit his shot but allowed himself to become so irritated…that he never got back in the match.”

The story of the 1919 Amateur and the 21-year-old who won it leaves little doubt that history is cheated by such interpretations.

Coming of age

Herron was born October 16, 1897 in the Hill District. His father’s stature as a bank president enabled the family to join Oakmont Country Club soon after it opened in 1904 and he groomed his three boys as golfers, each playing for Shady Side Academy and Princeton University. The elder Herron himself had a single-digit handicap and regularly competed in local amateur events.

Dave entered his first golf tournament when he was 11 years old, a junior event for boys under 18. He shocked everyone, including his family, when he advanced to the semi-finals. His true breakthrough came in 1912. At age 14, he won his first adult tournament, the Butler Invitational and with it recognition as one of the best golfers in the region.

Herron did most of his competitive play at Oakmont. At 15, he was excited to learn that the club was sponsoring its first invitational tournament for western Pennsylvania players. The field included the three prominent champions who mentored him at Oakmont: W. C. Fownes, Jr., Eben Byers, and George Ormiston. He played superbly and advanced to the semi-finals before losing.

A week later, he won the Stanton Heights Invitational claiming his second adult championship. Later that summer, he won a 36-hole medal qualifier for the first time, maintained that pace into match play and barnstormed through the field to notch his second victory of the 1913 season and his third regional title. At 15, he was the top pre-collegian in Pennsylvania.

He took a major step in his career at the 1915 National Amateur at Detroit Country Club. An East-West team match preceded the Amateur, and Fownes, as captain, chose Herron to compete for the East. Herron dispelled any doubts that he belonged and stepped into the national spotlight by defeating one of the country’s best golfers, Chicago’s Ned Sawyer, for the lead in the opening qualifying round. “Oakmont Lad Startles Oldest Followers of Game by His Remarkable Demonstration in First U. S. Championship in Which He Ever Played,” the headline in the Pittsburgh Gazette Times read. The tournament also proved to be a lesson in humility. He qualified for match play in Detroit, but lost in the first round and the national press lost interest.

He went back to winning in college. Herron led the Princeton golf team to a 9-0 shellacking of Harvard in the finals to win the team competition in the 1916 National Intercollegiate championship, which was played at Oakmont. Playing in the top slot, he destroyed Dudley Mudge, the Yale captain and medalist at the 1915 National Amateur. He routed the Harvard captain, Lawrence Canon, shooting under par in the process. He seldom missed a fairway, his approaches were straight for the pin and he putted well. He won the medal qualifier in the individual championship. But he and Princeton’s other top golfer, D. C. Corkran, were placed in the same bracket, which meant that one wouldn’t make the semi-final round. Neither flinched. Both birdied the 16th hole. But Corkran closed out Herron on the 17th, a defeat he took hard.

Under the cloud of war

America’s entry into World War I in April, 1917 turned the amateur golf world topsy-turvy. For Herron, it shortened his college golf career at Princeton. Most tournaments were cancelled in 1917 and 1918. He’d play in only two national intercollegiate championships on a team that was recognized as the best in the nation, one that he would captain in his senior year.

Several of Herron’s friends enlisted in the military. He was rejected because of his “excessive weight.” Herron played little for the remainder of 1917, choosing not to participate in the two local charitable tournaments that were held to raise money for the troops.

He returned to form quickly once he returned to school and began playing regularly at Princeton Golf Club, where he set a course record of 72. He won the club championship for the third time a few weeks later, then won the Atlantic City Invitational, his fifth tournament victory of note. But the spring golf season was cancelled a few weeks into the semester and Herron turned to water polo, diving and the hammer throw in track. Those sports helped him trim down and following his graduation in 1918, Herron was accepted into the Navy’s aviation service.

Before he left for basic training, he retooled his golf game. At the Allegheny Invitational, he tied for top spot in the medal qualifying rounds, then took down one challenger after another and defeated the veteran J. B. Crookston for the championship. “There is not a player in the state who could have defeated the kind of golf that Herron played,” The Pittsburgh Post reported. “He is a player without nerves.”

“There is not a player in the state who could have defeated the kind of golf that Herron played. He is a player without nerves.”

—The Pittsburgh Daily Post

Herron left for military service in July of 1918 not knowing when he’d next play golf.

As the amateur approached

After basic training, Herron was sent to the Naval Aviation flying school in Miami in October. It didn’t last long. One month later, the war was over and he was discharged. He returned to Pittsburgh around Thanksgiving and started planning for a business career. He also had to decide whether he could resuscitate his golf game after competing little during the past season. But the National Amateur was coming up and it would be played at Oakmont.

Given Herron’s Princeton education the first job he took seemed odd. He entered an apprentice school in a South Side steel foundry and became a low-level laborer. His entrée into the steel industry would start at the bottom. He left for work at 5:00 a.m., taking public transportation, heavy lunch pail in hand. His agreeable personality and physical strength helped with the hard labor he encountered and the challenge of working with recent immigrants whose lives were far different from his. But he had limited time for golf.

Pittsburgh was rife with speculation about which local golfers would contend at the Amateur. What had Herron been doing since the end of the war? How sharp was his golf? Would he compete at Oakmont? He hadn’t been seen on the links often. He chose not to play the West Penn Amateur. Still, the Pittsburgh Post reminded its readers, he had the “one necessary requisite essential to a champion. And that is golfing temperament.”

Herron took the entire month of August off work to prepare for the National Amateur. That gave him roughly two weeks to prepare for the first qualifying round on August 16th. He chose not to play competitively in favor of practicing fulltime at Oakmont. He focused on regaining the rhythm of his swing and his feel for the greens. He familiarized himself with the most recent hazards that had been introduced to toughen the course. Months of hard labor had made him stronger. Parts of his game quickly returned to form. Others did not. His tee shots were longer than they’d ever been, but were not consistently straight; his irons and short-approach shots were ragged—problems he hoped playing 36-plus holes per day would resolve.

Local hero

Dave Herron was the Steel City’s Bobby Jones. The local press glorified his history as a golfer, the tournament victories he piled up since his first at the Butler Invitational as a 14-year-old. The local consensus was that Herron would be a contender at the National Amateur.

The Pittsburgh sporting press spoke alone. Save for a brief early summer reference in the New York Times, golf writers elsewhere paid no attention to him. They focused on the headliners in what was considered the strongest field ever assembled for the National Amateur, one that included six former champions.

Two notable non-Pittsburghers, however, suggested he could emerge as a serious contender.

One was Walter Hagen, the flamboyant professional golfer and reigning National Open champion who was in town to write a syndicated column about the Amateur. He didn’t know anything about Herron. He didn’t watch him play until the later match-play rounds. And he was cocksure that Bobby Jones was the only young golfer with a chance to win on a course as long as Oakmont’s 6,707 yards. In his judgment, Jones was the longest, straightest driver in all of golf. His exceptional power would matter tremendously on a course where long, high tee shots were critical to clearing its omnipresent hazards.

But Hagen wanted to hear what others thought about the field and decided to spice up his column by asking Oakmont’s caddies for their views. They spoke with a single voice: watch out for Dave Herron. He was playing outstandingly well, intimately knew Oakmont and was calm under pressure. Hagen decided to watch Herron in the quarter- and semi-finals. What he saw, to his great surprise, was a golfer who’d have no problem keeping up with Jones off the tee.

Francis Ouimet of Boston, the former National Open (1913) and National Amateur (1914) champion and the most popular golfer in town for the tournament, also noted Herron’s potential. Ouimet was playing in his first national championship since the United States Golf Association reinstated his amateur status the previous year. He’d known Herron for several years, having first met him at a tournament in Baltimore during Herron’s freshman year at Princeton. Shortly before the first qualifying round at Oakmont, Herron and his childhood friend, Dwight Armstrong, defeated Ouimet and George Ormiston in a fierce match that made clear how far Herron’s game had improved.

Most striking to fans who tagged along was how easily Herron out-drove the long-hitting Bostonian. Ouimet spoke of Herron’s game to The Pittsburgh Press. If he didn’t win this year’s Amateur himself, he said, he would not be surprised if Dave Herron did.

The non-Pittsburgh sporting press knew little about Herron. In fact, until he played with Ouimet on the eve of the championship, it’s unlikely that he had practiced with anyone except his Oakmont buddies. He was about to show them on one of golf’s biggest stages.

No fluke

As the 1919 Amateur got underway, Herron consistently demonstrated all the requisites for winning. He blasted his tee shots high over Oakmont’s hazards. He extricated his ball with relative ease from its gnarly rough. He putted with confidence on its hair-trigger greens. He remained calm. He feared no one. Coming of age inside the ultra-competitive golf cocoon of Oakmont Country Club, he was primed to play against the very best, regardless of resume or national celebrity.

Arguably, the proper question to ask on the eve of the finals was whether Bobby Jones could stand up to Dave Herron. Pittsburgh’s sporting press posed that question and answered it unequivocally: No way. “Dave is at the crest of his game, which applies particularly to the snap in his short iron shots, which makes for accuracy,” E. Ellsworth Giles wrote in the Pittsburgh Gazette Times. “Herron to date has played the best golf in the tournament, which is, indeed, a distinction. His steadiness has been most marked, and there is little fear that he will break during the final round.”

Herron, for his part, spoke little to the press throughout the tournament. But on the eve of the final match, he expressed to the Pittsburgh Post the unflinching confidence that would help him carry the day. “This is the first chance I have to meet Jones in a tournament. I do not see any reason to be affected in my game by the fact that the match is for the National championship.”

When the final putt was made, it was clear that Herron’s victory was no fluke. He had dominated the 1919 National Amateur from start to finish. He turned in medal, or stroke play, scores much lower than those posted by Jones or anyone else throughout the week. He was the only player to consistently shoot in the mid-70s. And he was the first player ever to finish at the top in each of three discrete components of the National Amateur as it was contested in the early 20th century, which included an individual match play competition, 36-hole qualifier and a 36-hole American Golfer Trophy tournament.

And he did so against stiff competition. Jones’s temper tantrum aside, both golfers played exceptionally well in the finals match. It inspired USGA President Frederick Wheeler to call it “the finest finals ever played in any amateur championship in this country,” to which he added, “I never saw finer golf than that played by Davidson Herron.”