Look What’s Happening in Cleveland

With the opening of the Carnegie International less than a month away, I drove to Cleveland to see their inaugural international exhibition. Under the umbrella of “Front International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art,” projects happened as far away as Akron and Oberlin, but the majority were located in three Cleveland neighborhoods.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”268″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

With a loose theme of “An American City,” the rust belt city served as ground zero. Unlike the Carnegie International, which is museum-based with a singular curatorial vision, this first endeavor of the promised triennial was an independent venture that reached out beyond Cleveland’s art museums. It combined museum participation with installations and works placed around the city, following the model of site-specific shows like “Skulptur Projekte” in Munster (held every 10 years since 1977) or as a periodic part of the Spoleto Festival in Charleston, South Carolina.

Cleveland, currently in its post riot and comeback state, resembles Pittsburgh with revitalization and gentrification, and the artists of the Front take advantage of that change while simultaneously asking who wins and who loses in the process. They also look to history as a reminder of what and who contributed to the character of the city. The theme expands into issues of identity that go beyond the specificity of Cleveland to address international concerns. In this regard, the Front occupies the same conceptual space at the upcoming Carnegie International, where identity will be examined from a variety of points of view.

The Front is more a consortium of shows and events than a unified, focused exhibition. Under the seasoned eye of artistic director Michelle Grabner, a highly regarded abstract painter who was part of the curatorial team of the 2014 Whitney Biennial, a team was assembled, artists were chosen, and sites picked. This democratic process produced some great and not so great results.

As expected, the art institutions did what they do best with interesting and focused shows. The Cleveland Museum of Art, an august institution revitalized by an ambitious 2013 renovation, has been playing catch up with the art of our times because its esteemed director Sherman Lee (1958-83) did not engage with contemporary art. This has changed with a growing collection and a series of small exhibitions featuring artists such as Kara Walker or examining the cross pollination between Sol LeWitt and Eva Hesse, life-long friends who continually critiqued each other’s work.

The quality of those shows continues in the museum’s contribution to the Front, consisting of six one-person shows. The best, not only at the museum but perhaps in the whole project, was an enormous woodcut by Kerry James Marshall, accompanied by incredible studies where intense figures seemed to jump off the page. (Marshall’s comic book, “Rhythm Mastr,” that he debuted in the 1999/2000 International and will revive for this year’s show, was on view at the public library.) His woodcut, showing a mastery of an historical technique used in both Europe and Japan, presents a quiet, everyday scene of six black men conversing in a living room. Rather than part of stereotyped media representations, Marshall’s figures harken back to traditional paintings with two groups of three figures arranged to create depth in an essentially flat work, an effect that is underscored by the long blank wall that leads to a view into an empty Van Gogh-like bedroom. The formal spatial shifts within an ordinary scene serve both aesthetic and content purposes in a work that is insistent upon visibility for black men who are seen so rarely on the walls of museums, in what Marshall calls his “counter archive.”

At the Museum of Contemporary Art, a short walk away, the theme of the city characterizes the work of five very different artists. Of particular note was “Nightlife,” a 3D motion picture by Cyprien Gaillard. Shot entirely at night, Gaillard’s footage comes from four sites and is presented like a three-act play with a coda/encore. He starts with a slow, close-up pan of the surface of Rodin’s “Thinker” which sits outside the museum. Who knew it was damaged by a bomb, detonated as a protest against inequality in 1970? Once the camera circumnavigates the sculpture, the scene shifts to Los Angeles and non-indigenous plants swaying in the wind. Taking on almost human appearance, these fronds and branches create an eerie effect, especially when they come up against a chain-link fence that frustrates their freedom of movement. Another shift takes us to the annual fireworks display over the Olympic Stadium in Berlin, the site for Jesse Owens’ triumph in front of Adolf Hitler in 1936. Gaillard comes back to Cleveland to end with an oak tree that grew from a sapling gifted from the Fuhrer to Owens, placed in front of the school where he trained in his hometown. The mesmerizing images which float in and out of the visitor’s world are accompanied by a recording of “Blackman’s Word” by Alton Ellis. The repeating phrase, “I was born a loser” was re-recorded with “I was born a winner,” and the latter is heard at the end of the footage. While many will not read the label and understand the political content, they surely will appreciate the stirring images and sound.

The Akron Art Museum, in another rust belt city that was once known as the rubber capital of the world, is a third art institution that participated. Like the art museum in Cleveland, its building was enhanced with a glass jewel-box entry and new galleries in 2007. Its curator presented a group exhibition of international artists looking at the city as both site and concept with historical and contemporary references shaping urban identity. The incessant presence of media centric commodification, though from an earlier era, almost overwhelms the space as it blares from a separate gallery. Irish artist Gerard Byrne assembled 12 hours of radio broadcasting, overlaying nostalgia for simpler times with an understanding that only the scope of media saturation has changed.

Among the 12 artists and collectives, Nicholas Buffon, Jessica Vaughn, and Katrin Sigurdardóttir stood out. Buffon created his own city tour of Akron with small colorful works, placing himself in front of gay bars and gathering places. Vaughn reconfigured seats from public transport into a minimalist composition of dark grey on the white walls. The simplicity belied that public transport while critical to the wellbeing of a city also controls how we navigate urban areas. Both the content and the composition recall the poignant phrase in the stenciled work by Glenn Ligon at the Carnegie: “we are the ink that gives the page a meaning.” Another nod to minimalism is found in the work of Sigurdardóttir. Her practice involves gathering clay in her homeland of Iceland, shaping it into cobblestones in her NYC studio, and then distributing them in urban areas around the world, reshaping the ground people traverse in their peregrinations around the city. Her documentation of the process includes photographs of the changes that occur to her implants but also beautiful minimalist drawings of the slabs of clay.

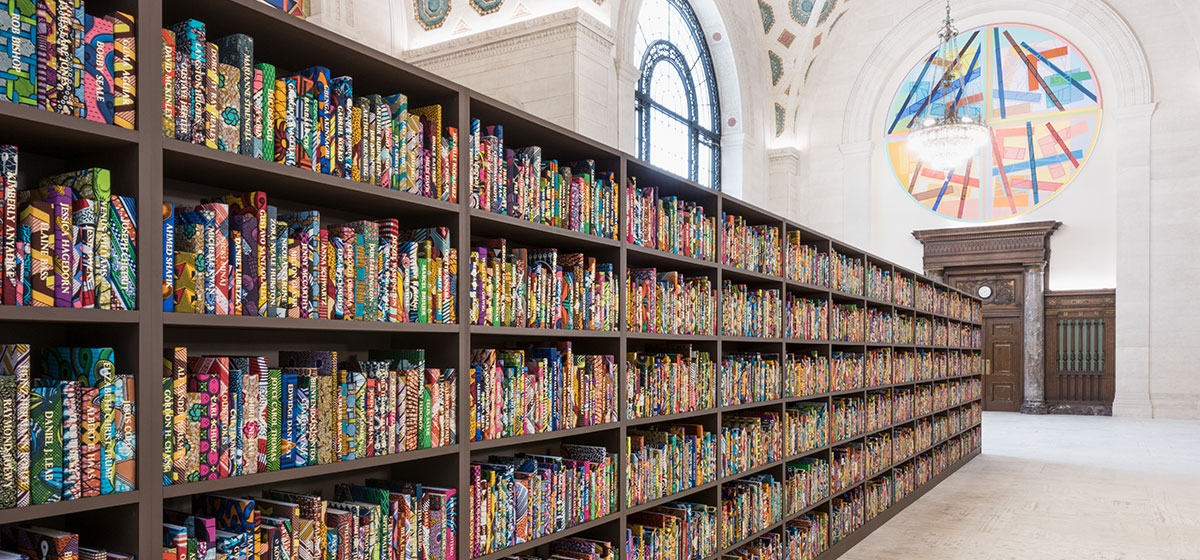

These three institutions created a diverse conversation about cities, past, present, and future with unexpected connections occurring as visitors experience the work. Reinforcing the museum work are several site-specific pieces sprinkled throughout Cleveland. Two of these pieces were especially memorable, one in the public library by Yinka Shonibare and one by Dawoud Bey at a small episcopal church in disrepair that was a last stop on the Underground Railroad.

Bey is an American photographer known for large-scale portraits of the marginalized. For the Front, he turned his interest to the Underground Railroad and the routes taken by slaves attempting to get to Canada. Instead of relying on historic documents, Bey imaginatively recreated the journey in a series of dark, moody photographs placed in the church. He inserted a dark, foreboding presence with black panels that hang among the pews. Like unmoving entities awaiting their fate, they recall former parishioners and/or slaves just passing through. His photographic images, shot in Cleveland but resembling scenes the escapees could have experienced, gradually emerge from their dark backgrounds, giving a shadowy presence to a story where fact and fiction merge. While the panels assert a concrete presence, the images are more suggestive of black ciphers slipping through the dark. Alone in the small church where the paint is peeling off the walls, you feel transported in both time and place.

Shonibare’s work is immediately recognizable as he has been constructing tableaux with mannequins dressed in the colorful, patterned fabrics associated with Africa, fabrics with a much more complex history due to cultural appropriation in colonial history and the tourist trade. They are just one clue in his scenes, many based on European paintings, that he is deconstructing the power and beliefs of imperialism and the colonialization of Africa by turning conventions and assumptions upside down. In “The American Library,” situated in the grand space of Cleveland’s public library, he once again incorporates these fabrics. Here they cover 6,000 books arranged on a typical library bookshelf. This collection, arbitrary yet significant, acknowledges first- or second-generation immigrants who have contributed to American culture while referencing the fact that the United States is a country of immigrants, the so-called melting pot. This archive is based on serious research, yet it is still random, just the tip of the iceberg. Shonibare invites visitors to use the website dedicated to this project on computers at the site. They can find short biographies of every named person, but they can also add their own immigration stories, building up the collection.

While not part of the Front, the Yayoi Kusama retrospective at the Cleveland art museum added yet another perspective to its theme. Her infinity rooms, which have been drawing strong attendance in every venue, allow us to viscerally experience the possibility of infinity in the present where we all exist.

The Front, on view through the end of September, offers a rich experience, even when if can’t make it to all the venues, including a show featuring Pittsburgh artists organized by artist John Morris. The overarching theme created a general platform, eliciting many responses and directions that mirrored the complexities of the American city. The theme provided a context and connections between works about challenging ideas, proving once again that artists have both creative and concrete solutions to our problems. I have no doubt that the conversations at the Front will overlap with those at the Carnegie International because it is the nature of the art of our times to deal with all aspects of our times.