John Fetterman, Public Servant

I was born in Reading, Pa., on Aug. 15, 1969. My parents, Karl and Susan Fetterman, were both only 19 years old at the time, so I was an “unplanned event.” But my mom and dad did get married and, as I matured and came to understand the circumstances surrounding my birth, the knowledge helped shape the way I looked, and continue to look, at life.

My father worked as an underwriter for an insurance company, and we lived with my maternal grandparents until I was two. We didn’t come from money, that’s for sure. Highlights of my early childhood were exciting excursions to the laundromat, and other everyday places.

I lived in the Reading area, but when my dad received a job offer in York, Pa., we moved there. That was in 1975. So even though I was born in Reading, I consider York, where I actually grew up, to be my hometown. Dad worked hard and, in time, became an insurance business owner himself, and much more successsful, financially. But that prosperity didn’t really kick in for our family until well after I began attending high school.

My parents were both Reagan Republicans, so I grew up in a conservative household. But we did not adhere to the twisted kind of conservatism that many people practice today. We were just a typical American suburban family. When I was nine or 10, I’d head out with my friends to play in the woods, and my mom and dad would say, “See ya.” We would disappear for hours, yet our parents would never worry. Growing up is so much different now.

My parents went on to have three more children—my two brothers and my sister—and I considered our life very ordinary. I figured that I would pursue rather typical goals in life, and never really considered the “bigger picture.” I was just growing up in a prosperous America and “doing my thing,” like millions of other middle-class, more or less privileged, kids just like me.

After admittedly sleepwalking through high school, I decided to attend a small, private, liberal arts college in Pennsylvania called Albright, where I played football and continued doing my thing. Then, after graduation, I attempted to earn an M.B.A. at the University of Connecticut, figuring that, perhaps one day, I’d have the opportunity to take over my father’s business. In 1993, however, during the final months of business school, my life was turned upside down.

One day, I was waiting for a friend to come and pick me up to go to the gym for a workout—but he never showed. Tragically, he had been killed in a car accident on his way to my house. That event was a real wake-up call for me. Never before had I been close to someone who died so unexpectedly, in such a violent, abrupt manner. I was stunned by the idea that one could, on any given day, wake up, have breakfast, kiss one’s family good-bye, and then disappear, forever. Think about it: You could have just 20 minutes left to live and not know it. The sudden death of my friend threw me into a whirlwind of grief and soul-searching. “If I were to die prematurely, what kind of an account could I give of my life?” I decided that I wanted something good to come from this tragedy, so I left business school and joined Big Brothers Big Sisters of America.

At Big Brothers, I was paired with a little boy in New Haven, Conn., who was just eight years old and had been born with AIDS. His father had just died from the disease, and his mother was in the final stages of dying from it, too. I can remember seeing her in bed, under a blanket, and she was, literally, just skin and bones. When she went to shake my hand, I remember thinking to myself—and I’m ashamed to admit it now—“Is it OK for me to touch her?” I had never experienced anything like that before, and it blew me away to think that this little boy would be an “AIDS orphan” before his ninth birthday. To think that he was living just six miles from Yale, one of the world’s most prestigious universities, an institution that he, more than likely, could never attend, upset me greatly. I suddenly felt sad and more than a little uncomfortable with my privilege. After all, I grew up with both of my parents (and still have them today) in a house where I was loved and cared for. I got to go to college and then on to graduate school, and had never done anything special. I was simply the beneficiary of what I call the “random lottery of birth,” a roll of the dice that we all get in life. Some win. Others do not, and it’s totally unfair. I figure that a boy shouldn’t have to face the world alone at nine years old.

It’s true that, in life, once you know something, you can never really “un-know” it. And given my experiences, I just couldn’t go back to the “typical” life I had planned. So I joined AmeriCorps (basically a domestic version of the Peace Corps) and moved to Pittsburgh to teach G.E.D. classes in the Hill District. But once there, I was again struck by the troubling realization of just how pervasive inequality is in our country. The young people with whom I was working in The Hill were coming in with fourth- or fifth-grade educations at best, but it wasn’t their fault. It was the result of the “random lottery” of their births: the time and place in which they were born, and to whom. The lack of support they experienced growing up in families where their parents (if indeed they had them) had to work several low-wage jobs just to put food on the table. This experience really fueled my determination to invest my life in combating such inequality.

Over time, I decided that I wanted perhaps to find a way to combine public policy, social work and economics to produce something useful for young people who were far less fortunate than I had been. So in 1996, I applied to graduate school and went to Harvard, to the Kennedy School of Government. I wasn’t sure exactly what my ultimate contribution was going to be, but it was definitely the direction I wanted to go, and I came out of the program with a full head of steam.

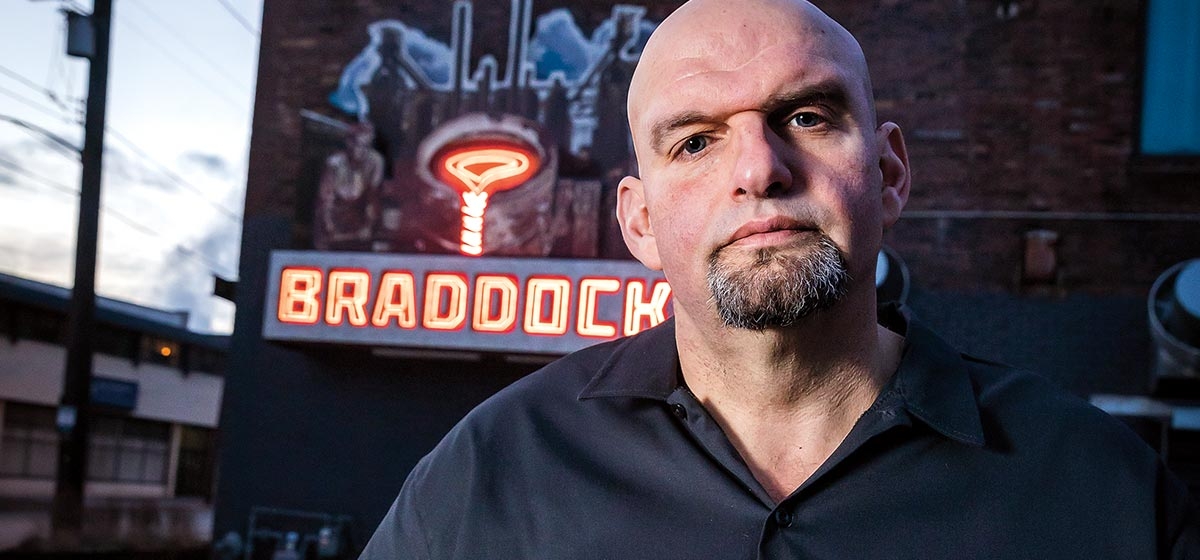

When I finished, I was offered another chance with AmeriCorps to start a program working with young people here in Braddock. I was aware of the town’s reputation. It was one of the places you were warned not to go. But somehow it felt ideal. This was at the height of the “dot-com” boom and many of my classmates were taking jobs with companies that had no redeeming social or community value that I could see. Most were just “get-rich-quick” schemes. Slap a “dot-com” on a business concept and, suddenly, you were making money. Conversely, Braddock felt authentic and real to me. So I turned up here again in 2001 and started working with the local youth, fully expecting to disappear into a life of service.

In Braddock, my job was to help young people get their lives back on track: to earn their GEDs, get their driver’s licenses, and find jobs—all things that were just handed to me when I was young. Over time, I developed a successful youth program that was recognized with an award in its first year from Allegheny County. We had a great run with that program—that is, until a couple of my students were gunned down in the streets. Those shootings sent me to a dark and reflective place. Sure, I could help some young people to earn GEDs, get their driver’s licenses and maybe find jobs, but I couldn’t do anything to change the circumstances of their births. So, inexplicably and perhaps reflexively, I decided to run for mayor, which was a big decision because I hadn’t run for any public office before, and I was not a longtime resident of Braddock.

Typically, the mayor’s job in any town goes to a person who has lived in the community their entire life. To run in Braddock was an unusual move for me but, against all odds, and with the help of the young people with whom I was working—who registered to vote and voted for the first time, in most cases—I managed to squeak out a victory… by one vote. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve thought, “What if that one person didn’t show up that day; if, say, he or she couldn’t get time off from work to go to the polls?” If that election had been held two years later, I would have lost by one vote because two people that I know voted for me previously were subsequently murdered. Once again, the trajectory of my life had been altered by tragedy. I will always carry a flag for the young people of Braddock, understanding that I’m where I am because of them. The community had been written off and discarded. That’s why I took it on. I didn’t grow up here. But if I had, I likely would have experienced an outcome similar to that of most of the young people here, who desperately need a helping hand to raise themselves up.

My arms both feature tattoos that mean a great deal to me. On my left are the numbers “15104,” which is simply Braddock’s zip code. On my right is a series of dates—each of which corresponds to the dates on which local kids have died here since I’ve been mayor. They were violent, awful deaths, and I remember all of them, vividly—all nine. To me, these events were not just fodder for local newspaper headlines or blurbs on the evening news. The lives of those young people, cut so tragically short, mattered. Those kids had families and people who loved them. I hope that I never get desensitized to such tragic occurrences because, if I do, I will have lost some of my humanity. I’ve seen what violence can do. It is usually the byproduct of totally meaningless issues, yet it comes with a permanent outcome, and you can’t ever un-know that.

When you think about it, Braddock’s history is, in a sense, romantic. In 1755, at the beginning of the French and Indian War, George Washington experienced his first days of combat here, as a military lieutenant. Later on, Andrew Carnegie, one of the world’s greatest industrialists, came to Braddock and built his first steel mill, which changed the world. That mill has been in operation since 1875 and, unlike other mills in the Pittsburgh area—Braddock’s mill has never closed. In fact, it’s the last of its kind in Western Pennsylvania. I think this town’s history explains a lot about what’s happened to the middle-class in our country. It also explains much about the growing inequality that I see. The path to middle-class life in America has continued to narrow for the past 40 years or so. When industry started to disappear, the fortunes of Braddock, and communities like it, went with it.

Not so long ago, Braddock was home to 20,000 employed people. I can only imagine how traumatic it must have been to have lived here when the mills were booming, only to see them close, up and down the river, tumbling like dominoes. That cataclysm must have triggered a kind of “fight or flight” response. “Do we stay and figure out how to make it work here, or do we take our chances and move to a new place?” Nine out of 10 people left Braddock. If you want to know what happens when 90 percent of its residents leave a community, look no further. Braddock had a terrible reputation when I moved in, but the young people with whom I’ve worked turned out to be outstanding. The community here is a good one. Braddock is just a place that deserved much better than it got.

Pittsburgh is a magical city. It’s home to some really great, historical neighborhoods, and Braddock is one of them. I love what I call the “malignant beauty” of this place. Sure, it’s not Walnut Street. If you want Walnut Street, go live in Shadyside. There’s nothing wrong with that. But while I was born in Reading and grew up in York, Braddock is the only place that has ever felt like home to me. It’s where I met my wife. It’s where all three of our beautiful children were born. It’s a place where no one thought a person like me could come and build a good life, but that’s exactly what I’ve been fortunate enough to do—and all through community service.