A Final Chat with Franco

My wife and I were at a party Friday night at the History Center, and after a cocktail, chit chat and getting our picture taken with Santa, we were going to check out the John Kane painting exhibit before the seated dinner. As we were making our escape from the crowd, however, I saw Franco Harris standing apart from the crowd, talking with TV journalist Sally Wiggin.

I’d met Franco maybe half a dozen times in my nearly 38 years in Pittsburgh but never spoken more than a couple words to him. But I walked over and said, “Happy Anniversary!” Sally raised her eyebrows and said, “Of what?” and then was kicking herself for not remembering that Dec. 23 would be the 50th anniversary of the Immaculate Reception.

Franco thanked me, and I told him I’d seen it on TV, that I was a sports nut as a 10-year-old and was at a family Christmas party in Cincinnati. As the rest of the family were socializing in other rooms, I was glued to the game on a small TV in the kitchen.

Franco was surprised that I was 10 (maybe he thought I was his age?). And he said, “People find it hard to believe when I say this, but I have almost no recollection of the play.”

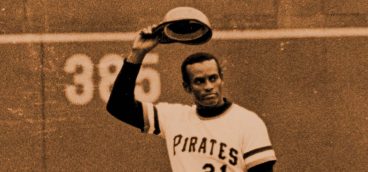

In case there’s anyone in Pittsburgh who doesn’t know, the Steelers were losing 7-6 to the Oakland Raiders in the ‘ 72 playoffs, and 22 seconds remained on the clock, when Terry Bradshaw threw a desperate pass to Frenchy Fuqua. The ball ricocheted off the Raiders hard-hitting defensive back Jack Tatum as he broke up the play laying Fuqua out. For an instant, the Raiders celebrated, until Franco came out of nowhere to catch the ball just before it hit the ground and gallop in for the winning touchdown.

“I saw Tatum hit Frenchy and we’re trained to go toward the ball. So that’s what I was doing. I’ve always had good reactions, and I was young then – a rookie. I saw the ball and the only thing I remember thinking as I reached down for it was not to break stride. I guess it was all instinct, and in football, I always had good instincts.”

It was electrifying for anyone who saw it — the greatest play in NFL history and it changed the Steelers trajectory from longtime losers to winners of four Super Bowls in the 1970s. I told Franco I assumed he didn’t want to get drafted by the Steelers, and he agreed. “This was the last place I wanted to come – here and Green Bay – mainly because of the weather. I wanted to go somewhere warm.”

“People didn’t expect much of us then,” he said, adding that they lost to the Dolphins in the next playoff game. We took turns recalling the players on that undefeated team, and Franco recalled the Dolphins game. “The game was in Pittsburgh, and I thought we’d have an advantage because of the weather – but the day of the game – the end of December — it was 60 degrees. And I thought, ‘that’s not a good omen.’”

I’d played in college and told Franco we had something in common that very few people did – catching a deflected pass and running it in for a touchdown – joking that I never understood why no one remembered mine at the midwestern football powerhouse Kenyon College. He laughed and we talked for 10 minutes, mainly about football, before another friend came over and complimented Franco on what a great player he was at Penn State.

After dinner, at the end of the evening, I stopped Franco for a second and said it had been a pleasure to talk with him. We shook hands, and he returned the compliment.

On a drive to Cincinnati the next morning, I told my son about my conversation with Franco and what a genuinely friendly, gracious, and unpretentious person he was. And in the days to follow, I wondered to myself why we had never featured Franco in Pittsburgh Quarterly. It was a mistake I intended to rectify.

And then came yesterday’s news that Franco had passed away. On ESPN, commentators showed The Immaculate Reception over and over as well as clips that reminded me what a great and powerful running back he had been. And, to a person, those who knew him said what a good man he was.

For Pittsburgh, of course, he was all those things and more. He was a shining example of what a citizen should be and of what a professional athlete could be. He used his celebrity standing to help this city more than any athlete I can think of in the nearly four decades I’ve been here. The examples are legion, but none surpasses his leadership of the Pittsburgh Promise in its efforts to help city children attain higher education.

Yes, his death is a great loss to football fans everywhere and to Pittsburghers everywhere. And as some would say, the timing was heartbreaking, coming as it did, days before his number was to be retired and before a major anniversary celebration of the Immaculate Reception.

But, what a tremendous and rare example he leaves for the rest of us – of grace and humility. And of commitment to doing whatever he could to make his community – Pittsburgh – a better place.