Finding New Ways

It’s around noon, and the winter sun shines on Fanny Edel Falk Elementary School at the top of the hilly University of Pittsburgh campus.

Through a window facing southeast from one of Falk’s language arts classrooms, it looks as if you can see forever—toward Pittsburgh’s east suburbs and beyond. Many of the students seem keenly aware of this, and they stare at that immense and gorgeous view. It’s a Friday, after all, and lunchtime approaches.

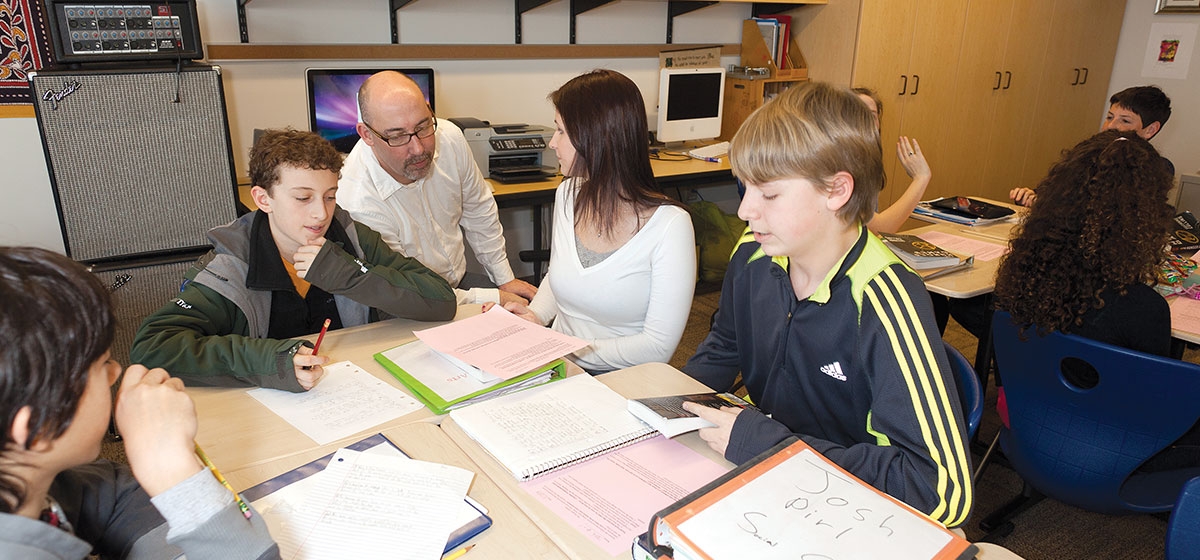

Maria Mrozowski brings them mentally back to the classroom one by one to participate in a discussion. Mrozowski graduated from Pitt in May and opted for an extra year of study at the university’s School of Education to get her master of arts in teaching (MAT) degree. She and her mentor, Greg Wittig—Falk’s middle school language arts curriculum coordinator—have been working on how best to focus students on thinking critically about literature.

Whether it’s literature, math or science, discovering how best to reach and teach students is a matter of critical importance across the nation, including Washington, D.C., where President Obama has called the nation’s educational system “untenable for our economy, unsustainable for our democracy and unacceptable for our children.”

The statistics are sobering. The 2009 report from the National Center for Education Statistics shows that U.S. citizens spend more money per student than any G8 nation and that U.S. teachers consistently work more hours than their international peers. Despite that, U.S. students are outperformed by students in most G8 nations in important indicators such as science literacy. U.S. students are distracted by more classroom disruptions than students in other countries, and they are often paid less after graduation than if they achieved the same level of education in another G8 nation.

And in a 2010 study of graduation rates in 48 states, the Schott Foundation for Public Education found that 33 of those states reported that black males are the least likely to graduate from high school.

The University of Pittsburgh’s Graduate School of Education is among the nation’s leading institutions tackling these problems. Last year, the School of Education celebrated its 100th anniversary, making it one of the nation’s oldest education schools. This year the school—which enrolls nearly 500 full-time graduate students and more than 1,200 total graduate students—is ranked 23rd in U.S. News and World Report’s list of the top 25 education schools in the country.

So how does this venerable education institution work to understand and educate the students and professionals of the future?

For Alan Lesgold, dean of Pitt’s School of Education, the answer is complicated. But, he says, it can be best understood through considering Falk School, a tuition-based campus laboratory school that educates students in kindergarten through eighth grade with the help of Pitt’s School of Education.

Falk, which opened about 30 years after the School of Education’s 1910 founding, is a prime example of how Pitt’s School of Education formulates research and develops new methods to educate successful teachers and students.

Some 300 youngsters are enrolled in Falk, and they go through their daily class regimens with the help of student teachers overseeing lessons and testing new ideas about how students can learn more effectively. Some of what those student teachers learn will eventually become doctoral theses and scholarly articles in internationally renowned journals such as Cognition and Instruction (which got its start at the University of Pittsburgh). And some of that knowledge will go toward educating student teachers to be more effective professional teachers post-graduation.

“Remember that a generation ago, if you made it through high school, you could get a job in a mill and have a really good salary,” Lesgold says. “Now all of a sudden that’s not enough. And now you have a cultural expectation in nearly every city that the most important thing is for your kid to get a diploma. But it’s a lot easier for your kid to get the diploma than to know your kid got a good education.”

The “diploma first” mentality often makes the role of educators difficult. If they try to implement innovative studies to improve education programs, they typically face two reactions. The first is skepticism that borders on distrust. “Anything that changes standards risks depriving a kid of a diploma,” says Lesgold.

The second is more grounded in an educational phrase that’s been fraught with controversy for decades: teaching to the test. “You have people who only believe in test scores,” Lesgold says. “And while test scores are an index of whether you’re heading in the right direction, they’re an extremely low threshold; you can pass all the tests you like and still not be prepared for life.”

Lesgold likens what teachers face daily to running a three-ring circus. “They’re in classrooms with 20 to 30 students, and there’s public demand from parents for tailoring each child’s experiences to his or her personal needs.” Teaching teachers how to manage that circus requires observation of successful teaching and teaching experience—the kinds of things they learn at Falk.

For example, when Falk was recently renovated and expanded, the university added video capability so that teachers can review classroom episodes in the same way that sport teams dissect game films, and get first-hand demonstrations and reviews of principles that were wholly abstract in their own instruction.

Consider the issue of high dropout rates for young black males. Lesgold, like just about anyone who attempts to answer these troubling numbers, is hard pressed to provide a concrete solution. “We don’t know how to get all of the youth who drop out to stay in school. So, we’re… beefing up our capabilities in the areas of motivation and engagement so we have researchers who can help develop better approaches.”

And it turns out that research—not teacher instruction—is what puts Pitt’s School of Education on the national map.

Robert J. Morse, the director of data research for U.S. News and World Report, stresses that when U.S. News ranks Pitt’s School of Education as the 23rd Best Graduate Education Program in the U.S., it’s not referring to how well the school trains the teachers of the future.

“We’re not trying to measure which schools are the best at producing the best teachers, except in the most indirect way. Our rankings relate to doctoral programs, the quality of research conducted by the education school, the number of Ph.D. students, entrance requirements into the doctoral program, and faculty awards. Currently, we don’t have the resources or the scope to research teacher education.”

Regardless, Lesgold says good research is what makes good teachers. And in the face of dire statistics from any source, Lesgold says, a good teacher is someone who understands the environment in which they work and cares about improving the lives of their students.

“A good teacher knows how to get across the hardest ideas and understands the different ways that knowledge grows in different kids. A good teacher respects and is able to motivate kids and is sensitive to their lives outside of school. A good teacher knows that learning comes from interactions—with teachers, with peers, and with artifacts in the world—and knows how to promote for each child the kinds of interactions that will lead to learning. A good teacher is a role model of self-directed, life-long learning and of moral strength.”

Is the School of Education successful? It would seem so. Pennsylvania’s state tests for special education, for example, were developed in Pitt’s School of Education. A widely read and often taught book about how to teach composition, “Ways of Reading Words and Images,” was co-written by Anthony R. Petrosky, associate dean of Pitt’s School of Education. And Kakenya Ntaiya, a doctoral student at the School of Education, was named a 2010 National Geographic Emerging Explorer last year for her work educating young girls in a small Kenyan village. That’s in addition to teachers like Wittig, who work to create a classroom environment where some language arts students seem to know more about literature and media than most adults do.

Back in that classroom on the sunny Friday morning, Mrozowski and Wittig have given their students a worksheet with two specific questions about occurrences in the final chapters of “The Hunger Games,” Suzanne Collins’s popular 2008 novel about a dystopian North America of the distant future. But the two adults in the classroom seem less concerned with the worksheet than with getting the kids to share their thoughts coherently with one another.

As students discuss the book in groups of four or five, Wittig explains that his ultimate goal is to “prepare kids for life,” rather than something more conventional, like a standardized test.

The focus of his language arts classes is on discussion and reading and encouraging kids not only to understand what’s on the page in front of them, but also in the world around them. It’s a focus that has developed gradually. The laboratory school environment is such, he says, that, “We’re free to react to where the students are, what they’re doing, how they’re learning, and seeing what emerges from that.

“The idea for us is that you want to show kids how to learn and to encourage them to be curious and intrigued. That’s what’s most important for us.”