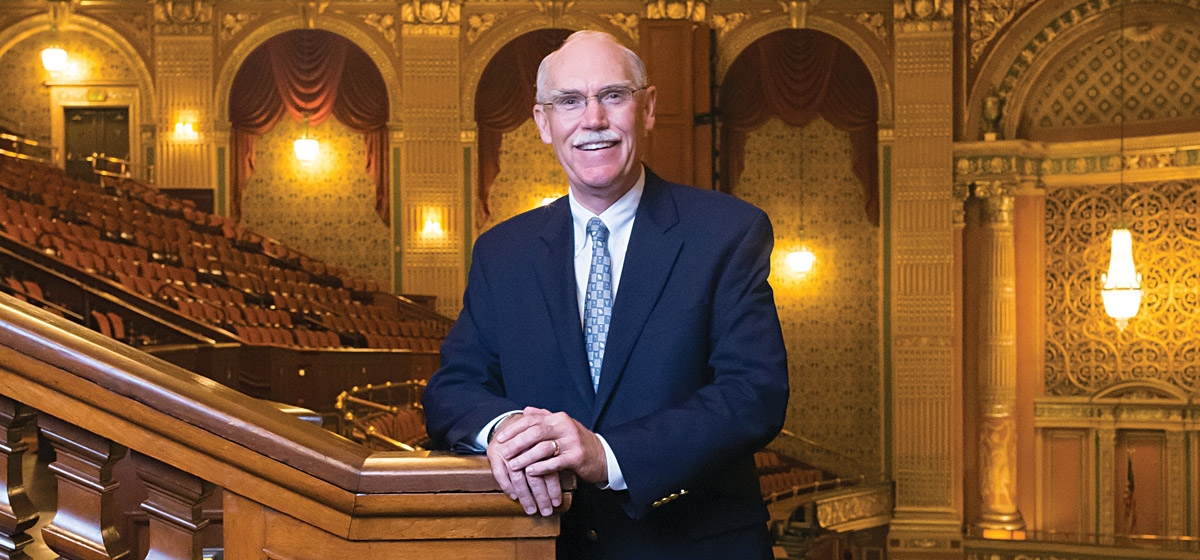

J. Kevin McMahon, Arts & Culture Executive

It’s not a secret, but I actually was born in Pittsburgh. I don’t talk about it, not because I’m not proud of Pittsburgh; Pittsburgh is great. But in Pittsburgh, if you say you were born here, everybody expects you to know everything about it. When I was a little kid, my family moved, so I did not grow up here and, hence, really did not know Pittsburgh before returning in 2001.

I grew up in Connecticut, which was interesting. There’s a lot of history there. We lived in Fairfield, so I was basically a suburban kid. My dad was a pharmaceutical company executive his whole career and commuted into New York City five days a week. Shuttling back and forth like that was, especially in those days, quite challenging. To be sure, his days were very long.

Of course, I had many wonderful opportunities as a result of living near one of the greatest cities in the world. Our family would go into town to see Broadway shows and to attend concerts and museums. It was great in many ways. But it was also very homogenous. I’m talking about in the 1960s and ’70s. And like a lot of teenagers back then, I was looking for adventure.

When it came time to think about college, most of my friends wanted to stay in New England to attend the “right” schools. But that wasn’t for me. I wanted to go west, and I stumbled upon a little liberal arts school called Hiram College, in Ohio, and that was it. It was the perfect place for me. Hiram was a very progressive institution; still is. And I just kind of “found myself” there.

My first college roommate was a good guy. But one evening, early on in our freshman year, he told me that he had never been to New York City. Now, I didn’t think there was a person alive who had never been there. This was a wake-up call because, not only had he never been to New York, but, even more shocking, he didn’t care that he had never been there! I couldn’t believe it and yet, at that moment, something clicked and I thought, “Wait a second, Kevin. There’s a whole world out there. There are still many people to meet and places to explore.”

At Hiram, I met my wife, Kristen (who was also, coincidentally, from Connecticut), and started my working life as a student in the college’s food service. It paid the bills, and by my senior year, I was in charge of all the food service at Hiram—the dining halls and 300 employees—and learned quickly about responsibility. If on, say, a Saturday night, the pot and pan scrubbing guys decided to call off, I would end up doing that myself. Or if the floor guy didn’t show: It’s two o’clock in the morning and I’m mopping the floors because by six, the dining halls must be ready for the next wave of hungry people. No excuses. I didn’t mind because that was the way I was brought up. One had to take responsibility. I stayed on at Hiram for about 18 months after graduation and worked for the college’s president and vice president doing some admissions and development work. Then I got my first “real” job at a small, all-women’s liberal arts institution named Kirkland College, in Clinton, N.Y. Soon after, Kristen and I got married.

Kirkland was the complement to Hamilton College, a distinguished men’s institution. Many colleges were going co-ed in those days, but Hamilton decided it would take a different path. Instead of bringing women into the ranks, it was going to create, across the street, a new college called “Kirkland” for women only. And like a lot of plans, it was sort of working—for a while. Kirkland had been in existence for about seven or eight years by the time I got there, and I was the “token” male. Practically everybody in the college was female except the president, Sam Babbitt. I was very young, and it was a great experience because I was exposed to a whole new way of seeing the world. The women there were assertive and many were brilliant. I had been working there for about a year-and-a-half when Kirkland got into financial trouble and was merged into Hamilton. Kristen and I had been married for only maybe eight months, were starting our careers and then “poof”—no job. As it turned out, being “merged-out” at Kirkland was perhaps the best thing that ever happened to me because I soon got a call from a person whom I had met through Hiram, who said, “We’ve got a big capital campaign to launch at Case Western Reserve University, so come on over.” Within a month, I had a new job in Cleveland.

I was the youngest development person on the staff at Case Western, which, in those days, was in the top 10 in terms of annual fundraising of all universities in the country; right up there with the Ivy League schools. Today these numbers seem tiny, but we had a five-year campaign to raise $214 million, one of the largest in the country, and about 70 fundraising professionals on staff to do it. Those were heady days. We were really doing big stuff, and I had five or six different jobs during the 4½ years I was at Case Western. I was “the kid,” you know? The president would say, “We have a new initiative. Does anybody want to tackle it?” I’d jump up: “I’ll do it.” It was a wonderful environment and I learned the art of fundraising there.

Opportunity knocks

Anyway, while at Case Western, I met a person who ran a fundraising consulting company, who also happened to be a Hiram alumnus. He said, “This campaign at Case Western is wrapping up. Why don’t you think about coming to work with us?” The company was located in New York City and it specialized in arts management. In fact, Carnegie Hall was one of its big assignments. Then the company informed me: “We have this one little client that’s actually still in Cleveland, so maybe you could just work on that for a while.” Well, a little while turned into three years. That client was Playhouse Square, which provided my first major exposure to arts management. I wrote a business plan. We hired a president and assembled a board. I got along famously with the president we hired, and he wanted to hire me on permanently. But what would I tell the fellow that hired me at the fundraising consulting company in New York? I was really torn. No matter which job I chose, I was going to upset one of these two fine people, both of whom I admired and respected. So I did the only noble thing: I wished them well and left both of them.

At any rate, Kristen and I had started a family by then, so we decided to circle back east and actually ended up living in Connecticut, in Fairfield, no less. It was nice to be close to family again. Then I worked in New York City for about nine years at The New School for Social Research as its vice president for development, which afforded me the opportunitiy to meet many fascinating people including New School President Jonathan Fanton, who became one of my mentors (and wound up being president of the MacArthur Foundation and is now president of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences). The New School was a quintessentially eclectic, multifaceted institution founded in 1919 as an outgrowth of a burgeoning dissident movement at Columbia University. The intellectuals there, who had been persecuted pre-World War II, formed what was called the “University in Exile,” a graduate program in social science. They also created a school of public policy. But the really cool thing was Parsons School of Design, which was also a part of The New School. The institution provided a stimulating environment for a young person like me at that time to continually open up his mind.

The only thing that wasn’t wonderful was commuting two hours each way every day into the city. This was in the days before cell phones and laptops, mind you. And the only good thing about a two-hour commute, most of which was by subway and train, was that I had time to read—up to five newspapers a day. After a while, one gets a sense of what’s really going on in the world.

I was going home on the train one evening, reading The New York Times, and learned that the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts had hired a new president. Then I looked at his picture: “Hey! I know that guy!” It was the former president of Playhouse Square, whom we hired and with whom I had worked, Larry Wilker. So I called Larry to congratulate him. He said, “Kevin, you’ve got to come down here. We need good people.” I said, “Sure. We’ll bring the kids down in the spring.” He said, “No, no. You’ve got to come down here right now. I want to hire you.”

“What attracted me to The Cultural Trust was a chance to make a true and lasting difference.”

— J. Kevin McMahon

Now, I hadn’t actually talked to Larry in five years. But within a month, I was down there in Washington, D.C., working with him and a great group of people. That’s when I got back into the arts management side of things. Working at the Kennedy Center…Wow! It was the big time. It was there that I received my first invitation to dinner at the White House, where I met all kinds of larger-than-life people. And as with The New School, I stayed there for about nine years. Then off we headed, on our next adventure, to Pittsburgh, where my life story actually began.

Downtown transformation

I was really looking forward to it. As important as the Kennedy Center was and is for our country, at the end of the day, it was just about arts and culture. What got me hooked on The Pittsburgh Cultural Trust (other than Jim Rohr, who was the board chair at the time and relentless in his pursuit of me, and founding president Carol Brown, whom I admire greatly) was the fact that it is not only an arts and cultural institution, it’s also an economic development organization. When it was founded 30 years ago by Jack Heinz and his so-called “Band of Dreamers,” it was a game-changer for Pittsburgh. These founders were asking an important question: “What can we do to make our city better?” What attracted me to The Cultural Trust was a chance to make a true and lasting difference. In my 14-plus years here, I believe that we have helped to make this community a better place.

When I came to The Cultural Trust in 2001, people were saying, “Wow, look at how great our Cultural District has become,” to which I would respond, “Yeah, it’s pretty good.” But people were still afraid to walk the streets downtown. And I looked out our office windows, right across the street on Liberty Avenue, and there were still half a dozen porn shops and “Triple X” establishments. Over time, our Cultural District had become, shall we say, a “different” kind of entertainment district. But in the late 1800s and early 1900s, it was a legitimate place for theater. The Alvin on Sixth Street and the Gaiety, which became the Fulton (and is now the Byham Theater), were prominent in the United States and presented world-class productions, even pre-vaudeville. Then in the 1920s came the advent of “big cinema;” the Loews Theater (now Heinz Hall) and the Stanley Theater (now the Benedum Center). It was a thriving entertainment district until the 1960s, when we saw the demise of urban centers in the U.S. in general. At that time, one of the few things that was still bringing people downtown were large movie houses, but then came changes in the anti-trust laws which separated the ownership of the film studio producers from the owners of the buildings in which their movies were screened. Before long, the films being shown downtown were no longer first-run and the old theaters closed.

Those were dark days when The Cultural Trust was created. Not only was the city experiencing a mass exodus of residents to the suburbs, but also an exodus to other cities because the steel industry, simultaneously, was collapsing. And of course, the government was in paralysis just trying to hold things together. So this “Band of Dreamers,” with a lot of help from the local foundations, took the worst part of downtown and set out to make it into one of the best. They simply said, “We’re going to do this.” And it happened in a relatively short period of time.

There is an assumption that it’s like this everywhere; that every city has a great cultural district which presents a variety of first-rate arts and cultural activities and facilities. And I say to people all the time, “It is not like this everywhere.” I believe that we have a more vibrant arts and culture scene than any other city our size. Unfortunately, when people talk about all the great attributes of Pittsburgh, somehow we’re not thought of as a great arts and culture town. How do we change that? By promoting the truth about what we’ve done here to build and sustain the arts and culture. In fact, other cities are trying to emulate what we already have.

A couple of years ago, a story ran in The Wall Street Journal listing the top five cities in the country that were going to recover the fastest and grow the most as the recession of 2008 was winding down. They were the usual suspects. But in the second paragraph of each of these cities’ descriptives, the focus was on their prevailing arts and culture scenes. This key determinent would separate the great places to live from the also-rans. My wish is that we all support and promote our arts and culture scene when we talk about Pittsburgh—not instead of, but in addition to all its other attributes. No city can call itself “great” if it doesn’t have one.