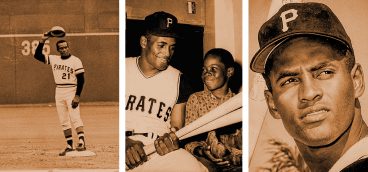

Eye on the Ball: Centerfielder McCutchen

Tuesday night, Aug. 25, 2009. There are 17,049 paying customers in PNC Park. If they are baseball fans, they are getting their money’s worth.

True, the Pirates are out of pennant contention. They are the sole resident of last place in the National League Central Division, as they have been for much of the past 17 years.

The Phillies are in a different division, the National League East, and in a different world. The defending World Series champions lead their division by five games. They are strutting their stuff, and they have brought hundreds—if not thousands—of fans with them from Philadelphia and its suburbs to help them do it. It is a short trip, after all, and an easy ticket.

If the Phillies fans are familiar with Robert Ardrey’s 1966 anthropology classic, “The Territorial Imperative,” a bit of wine before dinner has helped them forget its primary assertion. Although they are in enemy territory, where visiting fans traditionally hunker down and thank whatever gods may be for anonymity, the Phillies fans have blown their cover tonight. Many of them showed up wearing Phillies shirts, Phillies caps, Phillies jackets. Many more have been chanting loudly in support of their team since their shortstop, Jimmy Rollins, whacked a home run on the night’s first pitch.

Pirates fans do not chant much, as a rule, nor do they have cause to do so. But they are familiar with the territorial imperative. And they have spent the evening in full-throated support of their home turf. And so the chants have flown back and forth, hurled like weapons by the partisans; the louder the chant, the sharper the spear.

The crowd is excited, and that, in turn, has excited the players, who have done more than their share of things to make this a memorable night.

Ryan Doumit’s home run in the second inning tied the game at a run apiece, but Rollins homered again off Ross Ohlendorf to start the third. The Pirates reclaimed the lead at 3–2 in the sixth on a two-run homer by Steve Pearce. A succession of Pirates relievers has kept that fragile lead and handed it over to Matt Capps in the ninth.

Capps is the Pirates’ closer, the pitcher whose job is to turn ninth-inning leads into victories. He has been struggling this year. There have been precious few ninth-inning leads to protect, and he has squandered not a few of them. At season’s end the Pirates will do something almost unprecedented in baseball’s modern era: After failing to trade a young, proven closer, they will give him his outright release. Thus, when the Washington Nationals subsequently sign Capps to be their closer, the Pirates will receive no compensation.

This night, this inning will mark a turning point in the future of the Pirates franchise. And the inning starts badly. Capps surrenders doubles to Chris Ruiz and pinch hitter Ben Francisco. The game is tied, three all.

Shane Victorino, the Phillies’ center fielder, steps to the plate with two outs. Victorino, an All-Star dubbed by sportswriters “the Flyin’ Hawaiian,” is known for his speed, his combativeness, his penchant for making the big play when the big play is needed most. He is not known for his power.

Peering in at Victorino from shallow center field is his Pirates counterpart, Andrew Stefan McCutchen, 23, a rookie not yet three full months into his Major League career. The 11th pick in the 2005 draft, McCutchen is not merely the Pirates’ center fielder, but their shining star, the centerpiece of their organization. What he does for the Pirates— and what they do with him—will play a huge part in determining if Major League Baseball can survive in Pittsburgh under the team’s current ownership.

Andrew McCutchen grew up in Fort Meade, a small city in Polk County, Fla., little more than an hour’s drive from the Pirates’ spring training headquarters in Bradenton. The county’s oldest city, Fort Meade, dates to 1849, when settlers built around the cavalry post the U.S Army had established for its war with the Seminoles. Stonewall Jackson was sta- tioned there in 1851. Union soldiers burned his garrison to the ground 13 years later, but some of the surrounding homes survived and are among the 300 Fort Meade homes now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Fort Meade encompasses five square miles and fewer than 10,000 residents. About two thirds are white. African Americans, with approximately 22 percent, are the only significant minority. The one working traffic light is on Broadway, the city’s main thoroughfare. Blacks and Hispanics, almost without exception, reside south of the light, whites to its north.

“Everyone gets along,” says Kenny Eldell, one of McCutchen’s closest childhood friends. “The whole town’s like a family. But still, when you look at it, it’s segregated.”

Once they finish elementary school, the overwhelming majority of the town’s children attend Fort Meade Middle and High School. Andrew McCutchen didn’t. He was sent by his parents to Union Academy, a magnet middle school in Bartow, about eight miles from home. If you knew his parents, Lorenzo and Petrina, that would not surprise you.

No one in Fort Meade talks for a full minute about Andrew without paying tribute to his family. Yet they were not a family at all, at least in the legal sense, when Andrew was born Oct. 10, 1986, early in Andrew’s mother’s senior year in high school. They were both 17, although Lorenzo was a year behind Petrina academically. “We knew we loved each other, but that wasn’t enough, even though we had a baby,” Petrina says. “Lorenzo wanted to fulfill a commitment to the Lord before we got married. He wanted to be sure he’d be a good father and be in his son’s life full-time.”

She felt much the same way. She wanted a full-time husband as committed to her faith as she was, or she wanted no husband at all.

Lorenzo helped support his son by working at Junior’s Food Market, a Fort Meade convenience store, when he was not in class or playing football, basketball and baseball for the Fighting Miners of Fort Meade High School.

When she graduated, Petrina accepted a grant-in-aid to play volleyball at Polk Community College in Winter Haven, leaving Lorenzo to finish high school in Fort Meade. When he graduated, Lorenzo accepted a football scholarship at a more distant college, Carson- Newman in Jefferson City, Tenn.

Eventually, both returned home. Lorenzo became a youth counselor for the Peaceful Believers Church and Petrina the leading voice in the church’s choir, as well as a juvenile case-records manager for the sheriff ‘s department.

Only when Lorenzo accepted her faith did Petrina accept him as her husband, ending a marathon courtship. Andrew was 5 years old when his parents married. They celebrated their 18th anniversary in Pittsburgh, and McCutchen gave his parents a gift they will not soon forget. Of the 12 home runs he hit in his rookie season, he hit three that evening, driving in five runs in the Pirates’ 11–6 win over Washington.

His parents sent him to Union Academy because of its high academic standards. He was already showing signs of athletic precociousness, but they wanted more than an athletic prodigy. They wanted their son to be a good citizen and a serious student. And he fulfilled both those wishes.

He got good grades. His behavior was impeccable for the most part—although the few, minor exceptions stand out in his mind. Here is his rap sheet, which ends with a rap song:

1) He received a detention at Union Academy for freeing his shirt tail at the end of the day. “But the school bell had rung,” McCutchen protested. “But you were still on campus,” an instructor replied, putting an end to the discussion.

2) In high school he rested his eyes during a high-school Spanish class, not really sleeping, as he recalls. Who among us has not rested their eyes in class on rare occasion? Not Zoe Giannopoulos, who attended the same Spanish class. “Everyone got in trouble in that class,” recalls Zoe, who now works in the property assessor’s office. Not Kenny Eldell, who was cited for the same infraction by the same teacher. And certainly not Jason Payne, who leaned back while resting his eyes one afternoon in that same Spanish class until his chair tipped over and deposited him on the floor. Noisily, in case you wondered.

3) This one had nothing to do with school authorities. It took place in the summer, while Andrew was playing for an AAU traveling team. A teammate gave him a used truck, a red Dodge Dakota. The new owner lobbied his father for permission to install a modest audio system.

“That’s fine,” Lorenzo said. “But your mother and I don’t want you listening to songs with explicit lyrics. Anything you wouldn’t play in the house with your little sister (Lauren, then a pre-teenager, now a high-school cheerleader) in the room, don’t play in that truck.”

Andrew agreed, and Payne installed the audio system. Shortly thereafter, Andrew and his friends inserted a disc by a rapper named David Banner. “Mostly to hear the bass,” as Eldell recalls. Then Andrew committed another, more costly error. He forgot to remove the CD from the player and hide it at the end of the day.

Lorenzo looked in the CD player. End of CD. End of audio system. End of Andrew’s use of red Dodge Dakota.

McCutchen’s youthful misdeeds were spread over almost two decades, and they would not make him a candidate for the FBI’s Most Wanted list if they occurred during a single Boy Scout picnic. This is a kid of obvious substance; has been since he was old enough to crawl. “He was an honorable, respectful kid,” recalls Eldell, now a college student in Ohio. “He had his standards, and he stood up for them.”

“He had some friends, but not a lot of friends,” his father remembers. “He wanted to go to some parties, but not every party. He was never a wild child by any means.”

Being by far the best schoolboy athlete in a small town (not to mention the bearer of Lorenzo’s raffish genes), he was much in demand among the teen belles of Fort Meade and Bartow. But he dated only two. His major heartthrob was Ashli Cornelius, the pastor’s daughter. That relationship lasted almost to the middle of their senior year.

“He wanted to get her something nice for Christmas one year,” Petrina recollects. “But with all the ball he played and keeping his grades up, he didn’t have time for a job. I had some gold jewelry, and I had a necklace made into a bracelet for her.”

Andrew didn’t know it, but his mom was peeking out a window into the yard of their neatly kept, yellow brick ranch home at the corner of Lanier and Martin Luther King when he pre- sented that necklace to the pastor’s daughter and received a chaste kiss.

On a slow night in Fort Meade, Andrew and his friends used to go bowling. Except on Sunday, which was so slow, the bowling alley was closed. Andrew and friends sometimes rented a movie.

His hobbies, acquired in middle school, were drawing and writing poetry.

“It’s something I really love doing,” he said five years ago in an interview with Baseball America. “It calms me.”

In one of his favorite poems, “Step Up to the Plate,” written in high school, he describes a recurrent dream: “I’m in my first game in the pros,” he told the magazine.

“It’s on TV, and I’m starting in center field.” The dream ends, of course, with a home run by the author.

“Andrew was one of those rare kids who always knew where he was going and what his purpose was,” recalls Jeff Toffanelli, a roofing-supplies contractor in Fort Meade, over lunch at the local drive-in. In addition to being the baseball coach at Fort Meade, Tofanelli coaches the school’s varsity and junior varsity wide receivers in football.

Andrew McCutchen didn’t play baseball at Union Academy. The magnet school lacked a baseball team. Instead, by age 11, the boy was starring on the local Dixie Youth League Baseball League. That is how Tofanelli first heard of Andrew and where he first saw him play.

I asked Tofanelli when he decided to make McCutchen a starter on the Fort Meade High varsity as an eighth-grader. “The first time I saw him swing,” he said.

His faith proved justified. As the only eighth-grader on the Fort Meade varsity, McCutchen, then a shortstop, hit .591. That made him the leading hitter not just in Fort Meade, but in Polk County. He stood 5′ 8” and weighed 145 pounds after two help- ings of breakfast.

“Freakish,” said Tofanelli of the way the 13-year-old boy among 18-year-old young men could hit a baseball. “There’s a big difference physically among boys at those ages.”

Senior pitchers with long high-school pedigrees tried knocking him down. He got back up, brushed himself off and dug his spikes in deeper.

He played wide receiver on the junior varsity football team that fall. In his final game for that team, he caught two passes for touchdowns, ran back kickoffs for two more and scored a fifth on a punt return. It wasn’t the Fort Meade’s final JV game, but it was Andrew’s last, because Tofanelli promoted him to the varsity.

A leg injury the following year slowed his football progress. “The play was designed for Andrew to follow his block- ers outside,” Tofanelli recalls. “He saw an opening inside and cut back to go through it.”

The hole proved to be an illusion. It slammed shut, and McCutchen was sandwiched between tacklers. An ACL joint snapped, ending Andrew’s football season.

Eventually, he would recover well enough to be one of the top football recruits in the talent-rich state of Florida. As a senior, he signed a letter of intent to play for the University of Florida.

“He would have been playing wide receiver or cornerback [in the National Football League] by now if he’d gone in that direction,” Tofanelli speculates.

But baseball had been Andrew’s first love since he started enticing Lorenzo to play catch with him in the back yard as a preschooler.

Don Jacoby of the Major League Baseball Scouting Bureau saw Andrew play as a freshman and made a sugges- tion. Jacoby was not permitted to speak directly to McCutchen due to the boy’s tender age, so he talked to Tofanelli.

“He recommended we shift Andrew to the outfield to take advantage of his speed,” Tofanelli remembered.

Good suggestion. Tofanelli took him up on it the following season. Which is how Fort Meade’s four-by-100-meter relay team won gold in the state track and field championships—it consisted of Fort Meade’s starting outfield and its designated hitter.

It isn’t just how fast McCutchen runs, it’s how he runs. He appears to glide. His head doesn’t bob up and down the way most other outfielders’ heads do when they reach flank speed. His stays level to the ground. Thus the ball doesn’t seem to jump from one plane to another as he looks for it. He can turn his back to a line drive, losing sight of it, and instinctively know where to find it when the time comes.

McCutchen’s baseball statistics as a senior in high school read more like fantasy than reality. He led the county in every offensive category. He hit .781. That wasn’t his on-base percentage; it was his batting average.

“Remember,” you say, “He played for a Class 2A school. Two-A schools are the little guys. The big schools are up there in 4A through 6A.”

To which Tofanelli says, “I came here knowing that to build a respected program, we had to play the bigger schools. Outside of our conference games, which were mandatory, we played almost nothing but 4A through 6A schools while Andrew was here. And that’s true now, also.”

So here we are back in PNC Park with two out in the top of the ninth, the game now tied and McCutchen peering in from shallow center field at Victorino. Why from shallow center? In part because there is a base-runner in scoring position. But mostly because Andrew McCutchen always plays shallow—closer to second base than you would expect and so far from the center-field fence you would never expect him to get there in time to snatch a well- struck baseball before it struck that edifice.

Only great outfielders play shallow most of the time, and all great center field- ers do it. You have to be able to turn your back on the baseball, lose sight of it, then find it again—like a wide receiver running a deep route in football. McCutchen is lucky. Beyond being a brilliant wide receiver in high school, he has studied the art of playing center field under two outstanding tutors. Bill Virdon, the roving outfield instructor in the Pirates organization, has worked with him since he was drafted, stressing that five balls will drop in front of him for every one that falls behind him. Gary Varsho, who works with Pirates out- fielders once they reach the big-league team, has repeated the Gospel of Virdon and expanded on it.

You cannot make a sow’s ear into a Gold Glove outfielder, of course. Varsho estimates that a great center fielder is 70 percent the result of innate ability, 30 percent the product of coaching. McCutchen was already on his way to being a great cen- ter fielder when he was called up to Pittsburgh from Class AAA Indianapolis last June, but Varsho taught him, among other things, to control his adrenaline when base-runners challenged him and he had to throw the ball. That tutoring alone made McCutchen better.

Overthrowing a cutoff man will not be the problem tonight. Capps unleashes the 1–0 pitch. Victorino swings.

Pirates outfielders are taught to take a 90-degree turn to the left or right until they are sure in what the direction the ball is headed. A line drive hit straight at the outfielder is the hardest to judge. Pirates outfielders are trained to judge the most likely landing spot of such drives with the aid of their cap bill.

“If you see the ball come out of the hitting zone and it’s beneath the bill of your cap, you have to start in toward the plate,” Varsho explains. “If it looks like it’s over the bill of your cap, you need to turn and go get it.”

McCutchen took one step in, then a second. But Victorino’s bat had imparted enormous backspin on the ball. Topspin will make the ball dive faster than it would otherwise. But backspin will make it carry.

One wrong step and McCutchen was helpless. Probably he would have been anyway. Belatedly he turned and raced frantically toward the center-field fence. The ball got there before he did.

No error was charged on the play because the official scorekeeper is instructed to charge an error on plays where normal effort by a competent big-league fielder would have resulted in another, better outcome for the defense. Normal effort by an average big-league center fielder on this play would have resulted in a triple by Victorino. Which was the outcome on this play.

McCutchen blamed himself, of course, and some in the news media described the play as his “gaffe.” Certainly it proved he is human. But Lastings Milledge, playing left field that night, said the ball was uncatchable. And Garrett Jones, watching from right, doubted he could have caught it without the aid of a motorcycle.

It didn’t matter what anyone else thought. The Pirates trailed now, 4–3. And Andrew blamed Andrew.

He had one consolation: He was due up third in the bottom of the inning.

“God blessed me with the ability to make that kind of catch,” he says. “But I didn’t make it. By the time I got back to the dugout all I was thinking about was who was going to pitch to me.” Encountering Capps at the dugout steps said, McCutchen said, “My fault.”

He took a seat in the dugout and watched the Phillies’ closer, Brad Lidge, warm up. In 2008, Lidge’s first year with the Phillies, he finished with 41 saves in 41 opportunities. He won two games and lost none that year and posted a 1.95 earned- run average. It was one of the great tour de force performances by a relief pitcher in baseball history. But 2008 was over. And hitters were using Lidge, like Capps, for gunnery practice.

Not only that, but this night marked Lidge’s fourth appearance in four consecutive nights, a less than ingenious way to use him. McCutchen looked at him the way a hungry cheetah locks its gaze on a wounded antelope.

Luis Cruz, a last-minute replacement for Ronny Cedeno at shortstop, greeted Lidge by lining a single to shallow left field. Brandon Moss pinch-hit for Capps, and Lidge immediately threw a wild pitch that allowed Cruz to move to second base, where Brian Bixler, a pinch runner, replaced him. Moss now grounded a single to right field, and an error by Phillies right fielder Jayson Worth permitted Bixler to score and Moss to move to second.

Tie game. None out. Runner in scoring position. Last of the ninth. A single by McCutchen ends it. But singles in this situation are for peasants. McCutcheon had a message to send, and he sent it with a vengeance. He drove Lidge’s 1–0 pitch over the center field fence. Good morning, good afternoon, good night, Mr. Lidge. Thank you for playing.