Exuberance at the Warhol

Devon Shimoyama’s just-ended exhibition at the Andy Warhol Museum proves the enduring power of Warhol’s work 30 years after his death and shows that the museum has no interest in becoming a shrine to a self-referential and reverential hagiography. “Cry, Baby” brings a young talent to our attention, while simultaneously offering new insights into the museum’s namesake.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”302″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

Shimoyama obviously knew Warhol’s work. He was looking in particular at a rarely seen series entitled, “Ladies and Gentlemen.” Commissioned in 1974–75, it includes more than 100 works by the Pittsburgh-born artist of anonymous drag queens, some of which are also on view at the museum. The juxtaposition creates a context for Shimoyama’s autobiographical work that is rooted in lived experience as he navigates the world as a queer black man.

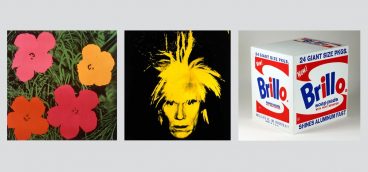

Warhol and Shimoyama have much in common. Their exuberant pop aesthetic, bordering on camp or kitsch at times, luxuriates in excess in both paintings and sculpture, while their content is serious and rooted in their times. Best known for figurative works that vacillate between identity and narrative, they both understand those who live in the margins and bring new kinds of people to the white walls of the museum, providing visibility and diversity. If Warhol hoped to democratize art by treating uptown and down NYC subjects as equals and by making icons out of Hollywood stars and Campbell’s soup cans, Shimoyama examines the disconnect in his own world between hypermasculinity and gay culture, and police and black males as he explores ways of being in the world. Both have had to navigate unfriendly territories, even though they are from different generations. When Warhol first came to New York City, the macho environment of the abstract expressionists blocked his acceptance. He hid his homosexuality for many years, while carefully constructing a shadow persona. Shimoyama’s identity as a queer black man is a part of, yet disrupts, the public narrative of the black man in America. He, too, navigates a fraught territory. While much has changed between the 1960s and the 21st Century teens, much remains the same as seen by comparing works about identity and race by the two.

Shimoyama is still a young artist finding ways to visualize his lived experience. In “Cry, Baby,” he first turns to various mythologies in order to, he says, “celebrate and invent some sort of new fictions of the queer black male,” while shattering contemporary myths about black men. This narrative element, from Daphne transforming into a tree to escape the lustful Apollo, to a snake entwined around a male body, to night spirits, provides a point of entry to the work. But nothing here is clear cut. His black figures merge into a black night sky, perhaps as a way to hide in plain sight. Daphne pays a price for her beauty, as she, too, tries to disappear. And the symbolism of snakes contains both strength, coming from non-western myths, and evil, as in the serpent in the Garden of Eden. These faceted fictional characters move beyond immediate impressions. Yet they serve as a way to distance black men from fraught stereotypes in today’s world. Not only do the figures shift fluidly from masculine to feminine, but their multi-variant identities are protected, camouflaged with decorative embellishment. His fancifully painted bodies are embedded in lush fields of flowers, glitter, and costume jewelry. But then, there are the eyes. Prominent, formed from photographs or found objects, including flower knobs, these eyes stare boldly, challenging the viewer: “I see you looking at me, and I’m looking back.”

That intense gaze becomes even stronger in the slightly newer works set in the quintessential barbershop, a neighborhood comfort zone for gossip, friendship and posturing. Salons and barbershops function similarly in black and white culture, but in the former, there is the added element of treating black hair, that marker for race and racism. The artifice of storytelling from the myth series is replaced by a recognizable reality, and the actors are frequently friends or the artist himself. Still reveling in the ability of decoration, now enhanced with more collaged elements ranging from feathers to costume jewelry, he hints at identity while simultaneously protecting the body. Shimoyama has made works that are more focused and direct, even autobiographic. His figures now declare, “We’re here and we’re queer.”

That assertive assurance is, of course, an act which Shimoyama admits, confessing that he rarely felt or feels at home in such sites of hypermasculinity. His men hide beneath the salon robes that are frilly with feathers or appliquéd silk flowers while they sit quietly. The proprietor is not present, seen only through his hands or his instruments—those sharp scissors, blades, and clippers. How much is made obvious, how much is ignored, and how much is masked here? That ambiguity, or perhaps the fluidity of gender identification, enriches the scene and hints at the many layers of the struggle to fit in. The added glitz references both a drag queen aesthetic and the macho posturing of wearing big, gold necklaces to appear more important. Hinting at the narrow divide between revealing and concealing an identity, Shimoyama conflates male/female, masculine/feminine, macho/effeminate in bold portraits.

This honesty gains swagger when the men are placed within their own bathrooms, shaving and shaping their hair. Frequently naked to the waist, their bodies are not clearly defined; rather they seem like templates filled in with a flat, ombre like color. These read as shapes more than bodies, linking them to the flatness of Warhol’s silkscreens, except Shimoyama often delineates facial features with delicate and assured drawings or collaged elements. The unusual colors, replacing black flesh that Shimoyama has now abandoned as too obvious, accentuate the bedazzled decorative effect of his work. Even the cord of the hair clippers is formed with large beads, curving like the snakes that used to twist around his men. Once again, the eyes dominate, drawing attention to sight and perception, visibility and invisibility, being seen or hiding/fading into the background.

The body-centricity of these works has been sidelined when Shimoyama deals with police brutality, where the artist leaves out the horrifying details, most importantly the body itself. Instead, he employs surrogates in momento mori sculptures, perhaps echoing Warhol’s intuitive recognition that repeatedly seeing horrific images robs them of the ability to affect us. Shimoyama sensitively masks the reality of death by creating an object of memory. He imbues ordinary objects with grief, caution, love and despair. A piece of driftwood becomes a flower- bedecked swing for Tamir Rice, the 12-year-old boy killed by Cleveland police in 2014, and glittery or flower encrusted hoodies for Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old killed by a neighborhood watch captain in Florida, and others lost to violence. There is something intensely moving and tender about these tributes, evoking a lost humanity.

It’s apparent from the very first look that Devon Shimoyama is wrestling with demons, taking on race, gender, violence, sexuality and the sites where they intersect. What might seem to be an emphasis on the surface of things is really a much deeper dive into perception, a process that begins with the obvious. This subtlety is even in the title of the show, “Cry, Baby.” The change from “crybaby” to “cry, baby,” encompasses both pejorative labeling and unleashed anguish. Shimoyama mines contentious territories. Yet, this show is anything but an essay on anger management. His work, imbued with strength and humanity, glamour and glitz, is a worthy successor to Warhol’s.