Cooking the Books

For me, it started with “The Betty Crocker Cookbook for Boys and Girls.” My sister-in-law loaned me her copy when I was 7. The 1950s spiral-bound edition depicted smiling, neatly dressed girls in aprons stirring batter and beating eggs in (now vintage) bowls with the boy in the background tasting from a pot resting on mid-century Formica.

I remember thinking those kids from an earlier time didn’t look like me, but I pored over those pages with the bright Kodachrome inserts of cupcake clowns and tin-drum cakes beside line-drawn illustrations of Funny Bunny Cake and Mulligan Stew. And something in my brain clicked. I wasn’t so interested in eating the food shown on those pages; I wanted to make it. That cookbook sparked a lifelong journey into the world of cooking and baking.

Amateurs and professionals alike have to start somewhere. If it isn’t in our childhood kitchen learning from scratch, it’s in the kitchen of our first apartment. From cookbooks and worn index cards to hands-on instruction, these experiences teach us to practice and experiment and to accept a few failures along the way to our successes. And sometimes the recipes, once a list of rigid rules to follow exactly, transform into mere suggestions—guidelines to work from toward new interpretations. Like a jazz musician learning to improvise, you think, “Aha! There are only a handful of rules. The rest is up to me.”

I’ve talked to friends about their first cookbook loves, and many credit Irma S. Rombauer’s “Joy of Cooking,” Betty Crocker’s cookbook with its red iconic cover, or Mollie Katzen’s game-changing 1977 “Moosewood Cookbook” for sparking the fuse of their inner foodie. But what about Pittsburgh chefs? What early influences nudged them to where they are today, and what cookbooks do they reference now to keep them moving forward?

“When I was in third grade or so, our English teacher had us make cookbooks,” said Neal Heidekat, chef de cuisine at Sonoma Grille downtown. “Everyone in the class contributed a recipe, which she then made copies of, and we bound them all together with yarn and construction paper. I think I still have it.” The first cookbook to really impress Heidekat, however, came in two volumes: Julia Child, Simone Beck, and Louisette Bertholle’s “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” “They possessed an almost mystical quality when I was a child. My mother would pore over the pages, and then later that night we would have a wonderful meal as a result.”

Today, Heidekat finds himself returning to “The Great American Cookbook” by Clementine Paddleford, and he also occasionally follows Aki Kamozawa and H. Alexander Talbot’s blog “Ideas in Food. “When you read a cookbook, you’re really getting a glimpse inside another chef’s brain. It’s fascinating to see the various details that different chefs obsess over. We all have our idiosyncrasies.”

For Sonja Finn, owner and chef of Dinette in the East End, her original love was “The Frugal Gourmet.” “It was the first cooking show I ever watched, and I remember the first episode I watched. It was a weekend morning, I was probably 5, and my parents were still asleep. Jeff Smith was making omelets, which I had never seen or heard of. I went upstairs and woke them up and we made cheddar and mushroom omelets. They bought me the cookbook after that.”

“Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone” by Deborah Madison inspired Finn in a different way. “Deborah Madison is an excellent chef, and I love all her cookbooks,” Finn said. “But it wasn’t the recipes that got me; it was the cover shot. Deborah Madison in an apron with spoons propped just right on her shoulder. A vase of flowers in the background. She looks so powerful, confident, no nonsense and beautiful. That is the chef I wanted to be. I’ve never seen a better cover or a better picture of a chef.”

Finn doesn’t always turn to the written recipe for inspiration these days. Long hours and a head full of food ideas keep her inventing beyond the page. “After cooking professionally for 18 years, I pretty much have a style and a taste I’m going for. Six and a half years of daily practice creating new menu items at Dinette has made it easy for me to come up with new dishes without referencing a cookbook or similar source. This is not to say I don’t enjoy reading cookbooks. I may not cook a recipe from the book, but that doesn’t mean I don’t enjoy a good flip through, let’s say, a River Cafe cookbook. I go to the library frequently and flip through cookbook after cookbook, new, old, and really any cuisine.”

Chef Kate Romane of e2 in Highland Park reads a lot of cookbooks and eats out to keep herself inspired. “I usually let seasonal produce guide our menus, so having lots of reference material in your brain is good. I also think it’s good to keep yourself open to new flavor combos and techniques. I often ask my new chefs to take books home to look at.”

Today Romane’s new favorite is Yotam Ottolenghi’s “Jerusalem: A Cookbook.” But back at the beginning it was the staple “Joy of Cooking,” a gift from her Uncle Millard. “It’s like culinary school in 500 pages,” she said. “Everything from conversions to how to set a table—the basics are all there. I have the call number for the book tattooed on my arm as a reminder of where I started.”

Michele Savoia, owner and executive chef at the South Side’s Dish Osteria, learned to cook by watching and doing. Raised by his grandmother as a young child in Sicily, he experienced food as a daily event. “She never had a cookbook and did not write any recipes down. The most simple act of shopping, prepping, cooking and making a meal just became an intrinsic part of everyday life.”

Savoia can’t remember a time when he didn’t worship food. “No matter what, a plate of good food and a glass of good wine will always be the most important goal for me to achieve.” He admits he has never been able to follow any recipe 100 percent, but later after he had entered his professional career, he discovered the cookbooks of Marcella Hazan. “Some very good classic recipes,” he said. “True, rustic, simple.” Today, Savoia likes to browse magazines like Cucina Italiana, as well as websites and blogs. “This media age has contributed a wealth of information never before available.”

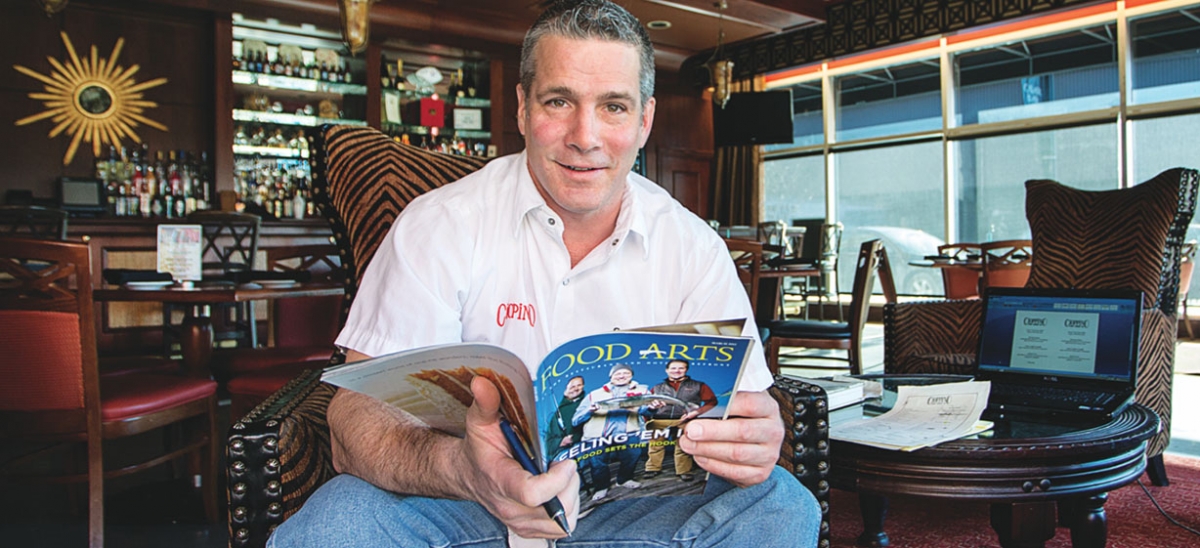

Chef Greg Alauzen of Cioppino in the Strip District remembers his mother’s “Betty Crocker Cookbook” with a bit of embarrassment, but Georges Auguste Escoffier’s “Le Guide” made an impact. Given to him by a mentor and a hard read, it provided all of the basics in French cooking. Today, Alauzen uses his cookbooks more as reference points—“To check on a brine recipe, or I’ll look at James Peterson’s “Fish & Shellfish” while I’m at the restaurant because we cook a lot of fish.”

Alauzen leans more toward magazines these days to stay current. He likes to keep up with Food & Wine and Bon Appétit, but his true love is Food Arts. “When I see it sitting on my desk, I take it home and read it cover to cover.”

As Chef Kevin Sousa transitions from his Friendship/East End restaurant tri-fecta of Salt, Union Pig and Chicken, and Station Street Hot Dogs to his new Braddock project Superior Motors, he’s reading up a storm of cookbooks. “Heritage” by Sean Brock, “Bar Tartine” by Cortney Burns/Nicolaus Balla, “Relæ” by Christian Puglisi, “On Food and Cooking” by Harold McGee, and “The Best of Croatian Cooking” by Liliana Pavicic/Gordona Pirker-Mosher are all on his list. His reasons for picking these books vary from a wonderful experience working with Burns, to admiring Brock’s willingness to go after what he wants, to Puglisi’s opening up a new way to think about food.

Sousa credits reading cookbooks as a major influence on his career. “I have always been a cookbook nerd. My interest in modernist food has not waned; neither have my cookbook-buying interests. New techniques are what reading cookbooks by contemporaries is all about. I attribute more of my cooking background to what I’ve read than whom I’ve worked for.”

The first cookbook to impress Sousa was Thomas Keller’s “The French Laundry” and his first cookbook ever was “The Art of Cooking Vol. 1” by Jacques Pépin. But he feels it was his introduction to the modernist (molecular) approach to cooking that pushed him. “It taught me to ask more questions and find the answers on my own. It pushed me creatively and intellectually. I feel like I have a group of tools that is now ever-present in my food, if even in just a subtle way of thinking and overall approach.”

Will there be a cookbook author in one of these chefs’ futures? “People ask me this a lot,” Finn said. “I’m undecided. I struggle against my shyness. Is it presumptuous of me to think people would want to read and cook my recipes? The truth is, it would be helpful for me to start writing this stuff down just for Dinette. Most restaurants have a kitchen notebook with recipes, but it’s 6-1/2 years in, and I’ve yet to write down a single recipe, even for the dough.”

Sousa has thought about it. “Not necessarily a cookbook per se,” he said. “I have a life story and I’d like to tell it.”

Romane dreams of it. “I love photography, and I obviously love food. I think we’ve had some really special dinners here [at e2] that I would love to be able to capture and share with a broader audience.”

Alauzen has a cookbook in progress. It doesn’t yet have a title, but he’s 60 recipes in. “I’ve been working on it for a couple years now,” he said. “It’s a collaboration of dishes—favorites things through the years. There’s a lot involved in a cookbook.”