Barebones Gets Its Teeth Into “God of Carnage”

The living room has always been one of the most dangerous places in America, because it’s a space that brings people into close contact, allows them to share their feelings, and usually happens to be where the alcohol is stored. As we’ve learned from plays such as “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf,” and “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” putting people and drinks in the same place for an extended period can be revelatory, but almost always turns disastrous. The living room is really a domestic stage where ordinary folks get to perform, acting out fantasies or taking on roles they would never portray outside of their homes. It’s perhaps the most convenient ready-made set in the dramatic world — Elizabethan in its simplicity — comprising merely a couch, a couple of chairs, and a table. Psychologically, we love the drama of this room, much as we love the drama of any performance area. When we enter our living rooms, we become budding Hamlets, earnestly projecting our antic dispositions onto those with whom we engage in conversation.

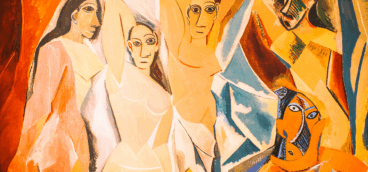

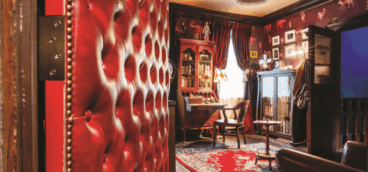

Ironically, “God of Carnage,” is a French play, written in 2008 by Yasmina Reza (translated by Christopher Hampton), which makes sense when you listen to the intellectual dialogue of the characters, referencing subjects such as the artist Tsuguharu Foujita, the civilization of Sheba, and the Darfur war. I haven’t been in many contemporary French living rooms, but in American ones you’re going to hear a lot more about sports and politics, so the easy banter regarding art and history is refreshing. In fact, the set, designed by the meticulously insightful Tony Ferrieri – with its mid-century prints by Rothko and Pollock, Bauhaus-style furniture, and coffee table art tomes — is a giveaway. Especially when there’s no television in sight. Toto, we’re not in suburban America anymore.

What makes this interesting is that it puts us in a world we think we know but really don’t. The four characters – two couples brought together by their 11-year-old children’s schoolyard fight (one hit the other with a stick, knocking out a couple of teeth) – devolve, over the course of an evening, into the kids whose conflict they are trying to resolve. To the playwright’s credit, this process isn’t linear, as each adult lurches in and out of their own emotional childishness, with an acuity that the talented cast never lets become predictable. If this were an American play the descent into chaos would be direct and unrelenting (like those works mentioned above); however, as a French contrivance, we are kept guessing. These are ruminative souls who were raised on Montaigne, not Monday Night Football, and even if they are not deep, they are thoughtful. All this adds to the perturbation that ensues.

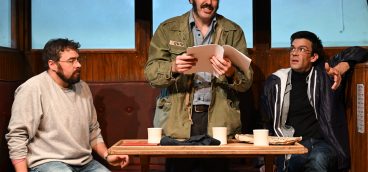

The first thing you notice about David Whalen’s character Alan is that, for a lawyer, he’s not as cutthroat as he would be in this country. He is, at least in the beginning, quite reasonable; almost polite. Mr. Whalen is one of those rare actors whose physical immersion into a role is complete, yet not tendentious or inflated. His is a quiet intensity that lulls you with understatement until something more is called for and, when it is, he can pivot with ferocity without foreshadowing it. Furthermore, he has a way of weaving his dialogue into the flow of a scene that allows him to step on another actor’s line the way we do in real life, without the false beat of ellipsis points that signal recitation, not reaction.

Playing his wife, the repressed Annette, is Gayle Pazerski who has – without giving the crux of the action away – the most demonstrative role in the show. She’s a woman trapped in a pantsuit with one of those corporate bow ties that went out in the 1980s, but she’s too afraid to relinquish the authority of this look, thinking it gives her gravitas, when it’s really a sign that she’s being strangled by the inattention of her workaholic husband, who is more in love with his cell phone than her.

Hosting these two are Veronica – portrayed by Daina Michelle Griffith, with a self-assured, yet manic fastidiousness – and her husband Michael – Patrick Jordan — who sells plumbing equipment, but unironically fantasizes himself a modern Spartacus. (This may sound strange, but if you’ve seen enough La Nouvelle Vague films, tropes like this make sense in France). Yes, these people all need therapy, and it’s no wonder their kids are screwed up.

What you probably won’t notice, because it’s so subtle and appropriate, is the direction by Melissa Martin. Especially the blocking which, on the exiguous Barebones stage (with a depth that can’t be more than 25 feet) could have been a mess, but Ms. Martin has found a way to make it both dynamic and organic. There is quite a bit of physicality on and around the large pieces of furniture, which most directors would have made look like a tennis match on a submarine.

Had this been staged in a large space, like the Public Theater, it would be a completely different performance, as the tension would have to be shown rather than felt by the actors, and the temptation to fulminate too great. We do get to see the eponymous violence, but it transpires not in the way you might think. And the conclusion, without the archetypal American sense of denouement, is also vivifying. In fact, “God of Carnage” begins and ends in medias res, and with a question rather than an answer, which an American play would rarely have the guts to do these days. This is not didactic theater, but experiential.

In fact, the exit music – always a major statement with Barebones — is Beck’s “Nausea” which, after you’ve experienced this stunning show, is extremely telling, and kind of like waving the Le Tricolore across the stage. Ultimately, this leaves us in the realm of Sartre, not Shakespeare, trapped in an existential living room with, apparently, no exit.

GOD OF CARNAGE continues through November 23rd at the Barebones Black Box Theatre, 1211 Braddock Ave., Braddock, $54.84. www.barebonesproductions.com