Art is a Conversation, Not a Lecture

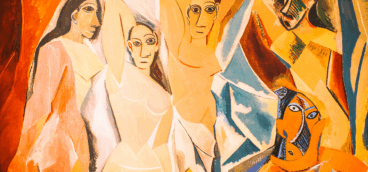

We read Stuart Sheppard’s recent piece for Pittsburgh Quarterly, “Is it Time to Stop Wearing Our Art on Our Sleeves?” with interest, and a fair amount of disagreement. Centering on Kara Walker’s recent exhibition at the Frick, which featured annotations from a select group of Pittsburgh-based guest labelists alongside the artwork, the article raises questions about artist intent versus audience interpretation.

But by diminishing the practice of artists sharing origins and intent alongside their works as “self-indulgent proclamations,” the piece falls flat. And by centering the op-ed on a Black artist whose work is bringing to light experiences of racism, followed by a critique of Pittsburgh Public Theater’s 2019 all-female retelling of The Tempest, the author leans on a sense of privilege and misses the very real ways art sparks conversation and drives change.

Art is meant to be a conversation. You can approach a work and form your own impressions, but dismissing the artist’s perspective outright shortchanges the depth and complexity of what’s in front of you. Critiquing artists simply for having a point of view is reductive. Films, paintings, performances, and poems often all come alive when we engage first on our own, and then circle back to consider context, intent, and commentary. Skipping that step misses half the impact.

Art today isn’t funded, or expected to exist, purely for beauty. Communities and funders increasingly look to art to create social benefit, spark dialogue, and drive impact in areas like equity, inclusion, environmental awareness, and civic engagement. When an artist shares perspective or intent, they’re opening a door for conversation. We can’t assume everyone comes from the same background or lived experience. Meeting audiences where they are, and providing context or resources to expand understanding, doesn’t water down the work, it makes it reach further.

And let’s be clear: art does influence attitudes and behavior. A “mere” painting, poem, or performance can provoke thought, empathy, and dialogue in ways that are subtle, powerful, and lasting. Throughout history, work created by artists and presented by arts organizations has been proven to expose corruption, challenge propaganda, and serve as a rallying cry for change.

Art isn’t neutral, and pretending otherwise ignores what makes it vital.

Sheppard states that ”not trusting your audience to form its own opinion is perhaps the greatest insult you can manifest in any creative act.” We’d argue that assuming an audience can’t form its own opinion while also knowing the intent of the artist is a larger insult.

Yes, don’t let anyone tell you what to think about a work of art, but also don’t ignore the artist. The real magic happens in the space between intent and interpretation.

—Patrick Fisher & The Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council

Stuart Sheppard Responds:

I am grateful for the response of The Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council to my essay, as I believe “conversations” such as this one are extremely important to our cultural vibrancy as a city. However, I am disappointed that their rebuttal resorted to the old ad hominem “privilege” trope, which is usually an indication of weak disputation, in that the person is attacked, rather than his or her argument. My hope is that younger readers of this exchange will come away with the insight that it is always appropriate to question didactic art, even if it means challenging the powerful institutions and museums that promote it.