Andrew W. Mellon: Building a Banking Empire

The year was 1866. With monotonous regularity, an older man and a little boy boarded the train in East Liberty for the short run downtown. The older man, attired in a long-tailed frock coat and a high-starched wing collar, spoke to the boy about matters of consequence; he spoke to him as an adult.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”14″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

The boy volunteered little; in rapt attention, he seemed to absorb rather than listen. The older man was Judge Thomas Mellon (1813-1907). The boy was his third surviving son, Andrew William Mellon (1855-1937).

Thomas Mellon, an Ulster Scot — commonly called Scots Irish — came to the U.S. from Ireland in 1818 and settled with the extended Mellon family already in Westmoreland County. Like young Henry Ford, farm life was not for him, and he soon left for Pittsburgh and a college education. He came upon a copy of Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography and read it several times. Resolution, frugality and industry would lead their devotee to wealth and prominence. Franklin’s precepts melded comfortably with the Scots Irish Presbyterian doctrine of industry and self-reliance. It formed a template that lasted not for one lifetime, but for two.

In 1837, Thomas Mellon graduated from the Western University of Pennsylvania (later the University of Pittsburgh). He was better educated than any of his forebears, and by his own design, better than his offspring. He read law, but not out of love of the profession. Lacking capital, law offered the best entry into business, and he set his sights on mortgages, foreclosures, real estate and property development. Deals started small, but his operations grew. In 1843, Mellon estimated his net worth at $12,000 ($300,000 today). At age 30 he set out to find a wife.

Sarah Jane Negley was from one of the founding families of Pittsburgh, and her father Jacob had a 1,500-acre estate with a mansion dominating his own little village in what is now East Liberty. Mellon intended to marry up for social standing. Money was not the decider, but it would help. Sarah Jane’s share of the Negley estate was $50,000.

The courtship was conducted with the thoroughness of a military campaign, with seemingly endless visits to the Negley mansion. Sarah Jane wasn’t swept off her feet but eventually succumbed. Mellon described the process in his 1885 autobiography: “There was no love beforehand so far as I was concerned. Nothing but a good opinion of worthy qualities; if I had been rejected I would have felt neither sad nor depressed only annoyed as to the loss of time.”

He chose well. The couple lived in a house he built on her property at 401 Negley Ave. for 57 years. Eight children came between 1844 and 1860. Only four boys survived to adulthood: Thomas A. (1844-1899), James Ross (1846-1934), Andrew W. (1855-1937) and Richard B. (1858-1933).

The Mellon family, as directed by the judge, was to be a financial unit much like the farming family that had been his provenance. And there was one profession and one profession only for the Mellon boys: business. “I secured free admission to their confidence from the first and participated in all their plans; and in return incurred their willing cooperation in my purposes for their plans.”

His boys were to be extensions of himself both economically and personally. His was a multi-generational plan; his progeny and their stewardship of his fortune was to be his immortality. There was little light or levity at 401 Negley; Thomas Mellon was a humorless, hard man.

Taking a lesson from Plato, he started his own school at home. The curriculum was practical: reading, writing and arithmetic. Poetry, literature and science had no place. The older boys, Thomas A. and James Ross, were rushed into business and received considerably less education than their father. As teenagers, Thomas ran a nursery and James a coal mine; both were successful.

Mellon’s sterling reputation in the law, buttressed by Sarah Jane’s family connections, helped him expand. Property, whether mortgages, real estate or minerals, was the common thread in all his investments. A bolder, less cautious man might have turned to operating businesses, and in Pittsburgh, manufacturing was the obvious choice. Here money could be made many times faster than with the judge’s painstaking real assets investments — or it could be lost.

The annointed son

In 1859, Mellon was elected associate law judge in the Court of Common Pleas and was ever after known as “the judge.” He enhanced his reputation and contacts through his judicial office and built his already sizable fortune. But in the quest for fortune and prominence of the first rank, he had fallen short; the money would simply not pile up fast enough. But the judge had a secret weapon: his sixth-born child, Andrew Mellon.

Andrew’s nearest sibling, Selwyn, died at the age of 9, and the death weighed heavily upon young Andrew, drawing him closer to his father. With failing eyesight, the judge drafted Andrew to read to him the serious works in his intellectual diet. In Darwin, Spencer and Huxley, Andrew read and absorbed the lessons of capitalism. The judge paid for these reading services at 25 cents per hour. He doubtless sensed Andrew’s precociousness and let his education run beyond that of his older brothers — but within bounds. Between 1869 and 1872, Andrew took a combined preparatory/college course at the Western University. He left without a degree. At the uncommunicative dinner table at 401 Negley, Andrew received top prize for silence; he always kept his own counsel. His character, set early on, was a contradictory amalgam of diffidence, inhibition and shyness, coupled with powerful confidence and self-sufficiency. Despite the onslaughts of wealth, fame and power, this mold was never broken.

A few months after stepping down from the bench, the judge founded a private bank, “T. Mellon & Sons” at 514 Smithfield St. Two years later, he erected a four-story iron-front building with a statue of Benjamin Franklin standing above the door. This was the bank headquarters for the next 50 years.

During his university time, Andrew spent every Saturday and time off from school at the bank. He absorbed its rhythms. Determining that Andrew and his younger brother Dick needed practical operating experience, their father set them up in a building supply business similar to that run by Thomas and James in East Liberty. Andrew piloted the enterprise. He sensed, however, that business was too good and got out just before the financial panic of 1873. He returned to the bank in time to stand by his father during the crisis. T. Mellon & Sons survived, but the judge was shaken and humiliated. He had to stop payments to most customers and nearly closed. At 19, Andrew was now full-time at the bank. Thomas’s growing confidence in Andrew coupled with his failing eyesight led him in 1882 to turn over T. Mellon & Sons to Andrew. He was 69; Andrew 27.

In the wake of 1873, it wasn’t much: modest profits and a very good name. Less well-educated, less articulate and far less a commanding presence than his father, Andrew might have been expected to have a caretaker mentality, cautiously expanding in the style of the judge. But beneath that saturnine countenance brooded ambition equal to that of Carnegie. The analytical skills he inherited from his father provided only the foundation, upon which rested vision, imagination and appetite for risk.

One of the early customers at the new iron-front at 514 Smithfield was Henry Clay Frick. Frick was building his empire of beehive coke ovens in Fayette County. Battered by the storm of 1873, he was stretched thin but sought to expand at the expense of his bankrupt competitors. The judge made a series of loans that grew under his tenure to over $100,000. In 1876, at the end of a meeting with Frick, he introduced him to Andrew. Frick was Andrew’s senior by six years. He was better educated and much more a man of the world. Frick called him Andy, but Andy always referred to the coke king as Mr. Frick. They became good friends and close business associates. Frick dominated the friendship, but the younger man’s accomplishments would far outstrip those of “Mr. Frick.”

In 1881, in partnership with Frick, Andrew acquired control of the Pittsburgh National Bank of Commerce. In 1883 he bought the Union Insurance Company and started the Braddock Bank. In 1886, again with Frick, he founded the Fidelity Title & Trust Company. With a larger financial base, he set his sights on Pittsburgh industry. Along with Colonel James M. Guffey, an inveterate oil prospector and promoter, he established and controlled the Westmoreland Carbon Gas Company and the Southwestern Pennsylvania Natural Gas Company. He was also a substantial investor in the Bridgewater Gas Company and the Shenango Valley Gas Company, and, while not destined to be a major Mellon enterprise, he financed John Pitcairn in the newly established Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company.

Dick Mellon joined T. Mellon & Sons as vice president in 1887. He became a full partner, pretty much splitting everything with his brother 50/50. As Andrew described it, “It was an outright gift…I just said to come in, and he came in, and we were partners.”

His favorite investment

Although he would make more money in oil, Andrew’s favorite investment was aluminum. In 1889, Captain Alfred Ephraim Hunt and two young associates, Arthur Vining Davis and George Clapp presented themselves at 514 Smithfield seeking $4,000 for their struggling Pittsburgh Reduction Company. Their prospects hinged on the patents of a young Oberlin College graduate, Charles Martin Hall, for the electrolytic reduction of aluminum from bauxite. The company was small, the technology questionable and the team, with the exception of veteran metallurgist Hunt, was unproven. It was a classic venture capital investment long before the term had been invented. It was an investment the judge would never have listened to, let alone made.

The wolf was at the door for the Pittsburgh Reduction Company (later Alcoa). The technology seemed feasible, but there were doubts. Andrew knew and respected Hunt. In the end, though, Andrew was won over by Davis, a 22-year-old with a pimento-loaf complexion and waxed ibex-horn mustaches. “I’ll tell you the worst,” Davis said. “I am a college graduate (Amherst) and the son of a minister, but I mean to pay.” Mellon was sold. Knowing the crew would never make it on the $4,000 they were seeking, he offered $25,000 to provide needed working capital.

There were losses, lawsuits, tariff issues and a host of problems scaling an entire new industry. The bank advanced more money, and Andrew joined the board, followed soon by his brother Dick. In 1894, their stake was 12 percent. With Arthur Vining Davis, Andrew had judged well. Alcoa became a huge success.

Striking out

Aluminum is big business; oil is the biggest business. The Mellons got into oil by fits and starts. Robert Fulton Galey, the judge’s old friend, convinced him to take a small position in a few wells along the Clarion River. The sums were modest, and the wells soon petered out. The judge didn’t like oil or oil prospectors.

By 1889 there were numerous oil strikes near Pittsburgh. William Larimer Mellon (1868-1949) was at the bank. W.L. was the son of Andrew’s older brother James Ross Mellon and eager to be a hands-on operator. John Galey (Robert’s son) fired his imagination, and the two of them convinced Andrew and Dick to back them. Success followed; money was advanced. The more success they had, the more money they needed. Gathering lines were built to bring the crude to Coraopolis where it was sold to Rockefeller’s Standard Oil.

They then built a refinery and began to sell refined products in competition with Standard Oil. The business grew, offshore markets beckoned and soon the Crescent Oil Company (35 percent Andrew, 35 percent Dick and 30 percent W.L.) owned 400 tank cars that carried oil East. They had baited the bear, and Standard Oil took action. The Pennsylvania Railroad, at the behest of Standard Oil, imposed crippling rates upon the Mellon enterprise. The Mellons counterattacked by building a 271-mile pipeline from Pittsburgh to Marcus Hook on the Delaware River. Standard Oil and the Pennsylvania Railroad threw up legal roadblocks. Pennsylvania, however, was the Mellons’ home turf. They had friends in high places, and the pipeline went through. It was the only pipeline in Pennsylvania not controlled by Standard Oil. They now had an integrated oil company with a refinery on the Delaware River.

By 1895 the Mellons were reputedly shipping 10 percent (probably high) of the nation’s oil exports. They had invested $2.5 million in Crescent, far and away the biggest investment they had ever made. They knew when to fold. In 1895, they sold the company to Standard Oil for $4.5 million. The profits were good, and they took no little pride in having bested mighty Standard Oil.

Act Three of Mellon’s oil investments began in 1900. The same inveterate prospectors and promoters who had previously led Mellon to oil caught Andrew’s ear again, and he backed them in a well at Spindletop, Texas. Spindletop spewed forth oil at a phenomenal rate of 40,000 barrels a day. It was the biggest gusher the nascent industry had ever seen. This operation was far bigger than Crescent, and it took far more money. The Mellons laid pipelines, built a refinery at Port Arthur, Texas and bought a fleet of tankers to service distribution nodes in several East Coast cities. Problems abounded: too much oil, narrowed profit margins and Guffey, a genius at finding oil, was a lousy manager. Andrew headed for the exits. Along with W.L., he went to New York and approached Standard Oil. Their unpleasant experience in the losing battle with Mellon over Crescent was fresh in their minds; they turned him down.

Andrew upped the stakes. He sent W.L. to Texas just as a major new field was opening near Tulsa, Okla. Standard again was the team to beat. As luck would have it, in November of 1906, Theodore Roosevelt pulled the trigger on the historic antitrust suit against Standard Oil. With little obstruction this time, the Mellons built a pipeline 400 miles from Tulsa to Port Arthur. They pushed Guffey out, and W.L. built a team capable of running a now sizable business.

Gulf Oil, as one of the seven sister international oil companies, became the crown jewel of the Mellon empire. In 1928, Gulf’s net assets were $650 million. Andrew, Dick and W.L. held 70 percent of the stock in the still-private Gulf Oil Company, the largest company ever to come out of Pittsburgh. Even on a lengthy laundry list of major Mellon investments, Gulf probably accounted for 40 percent of the family fortune. Reflecting on his turndown by Standard Oil, the laconic Andrew remarked: “They weren’t so smart, were they?”

A reasonable estimate of the combined worth of the Mellon family in 1900 would be $5 million ($100 million in today’s dollars). A decade later this number had probably increased 20-fold. How did Andrew Mellon do it? The judge once said that it might be a good thing if Andy lost a loan; virtually without exception it never happened. Andrew was a superb banker and a keen judge of character. Successful entrepreneurs are committed body and soul to the propagation of their enterprise. They are cautious but not normally skeptical. Carnegie and Westinghouse are prime examples. As F. Scott Fitzgerald observed, the test of a first-rate mind is to hold two opposing ideas in equipoise. Both skepticism and unwavering commitment were the heart of Andrew’s genius.

The other distinguishing feature of the Mellon system was reliance on family. As Andrew and the judge were of a piece, so were Andrew and Dick, and their nephew W.L. — only 10 years younger than Dick. Dick was well fed, well balanced and jovial. In the critical interviews with entrepreneurs who sought Mellon support, he filled the gaping holes in the conversation as his brother silently calculated the likely outcomes. He provided his psychologically fragile brother with crucial emotional support. Andrew pulled the trigger on every deal — no Andrew, no vast Mellon fortune. But without Dick, it’s questionable whether Andrew could have sustained the effort.

Disastrous marriage

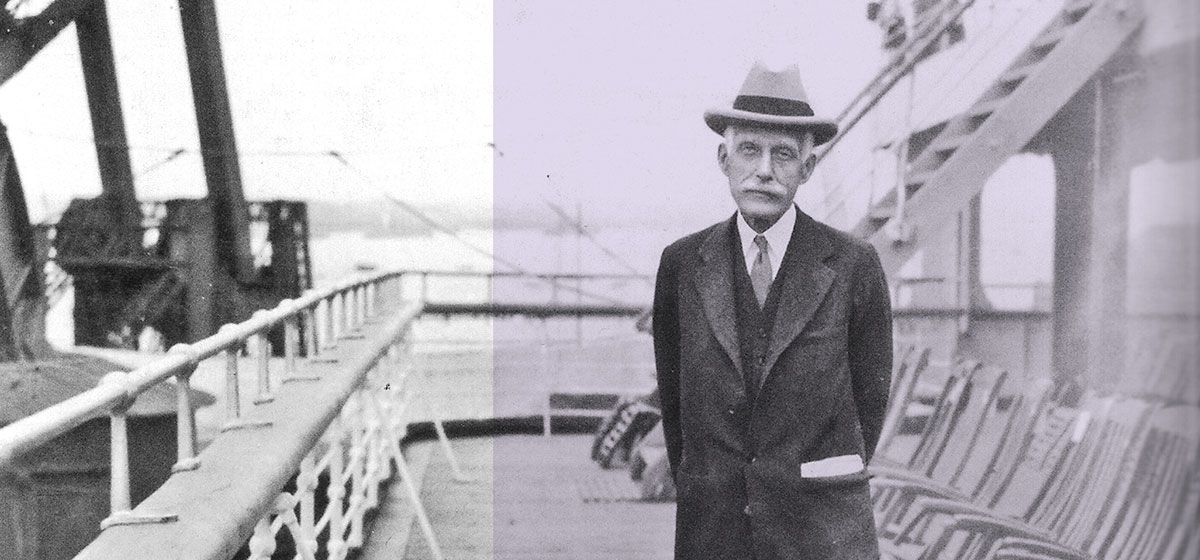

Dick married in 1897, leaving his brother a middle-aged bachelor, still at 401 Negley, taking silent dinners with his parents. On a crossing to Europe in 1898, Frick introduced Mellon to Nora McMullen, 19, the youngest of nine children and the only daughter. Her father was a brewer and gentleman farmer. Andrew visited the McMullens briefly and returned the next year to propose. Nora turned him down: “You must see it is a mistake… it would mean nothing but unhappiness for us both.” There was a 24-year age difference. Her life was the English countryside vs. grimy Pittsburgh. Mellon ignored common sense and advice from his father and smashed through every roadblock.

They were married in 1890, and problems arose at the start. When the newlyweds departed the train at East Liberty, Nora exclaimed: “We don’t get off here do we? You don’t live here?” The mystique of his wealth aside, Andrew Mellon was poor marriage material. He was consumed by business and was just embarking on his most productive decade.

A year after their marriage and the birth of their daughter Ailsa, Nora developed a romantic interest in an Englishman, Alfred Curphey. He was still married, had squandered his wife’s moderate means and was looking for ripe pickings. He came to Pittsburgh, smoothly talked Mellon into a $20,000 loan and took up an extended residence at Mellon’s Forbes Street home. He began squiring Nora around Pittsburgh during Andrew’s business travels. By 1903, on an ostensible visit to England, she took up residence with Curphey. In 1904 she told Andrew she wanted a divorce.

Mellon, determined to hang on, secured a promise from Curphey to forget Nora for 20,000 pounds. This bought Mellon sufficient time to see his son Paul born in 1907. The situation worsened. Having squandered his Mellon payoff, Curphey reunited with Nora in 1908. She beseeched Andrew for a regular allowance. He offered $10,000. Nora insisted on $20,000 ($500,000 in today’s money), most of it earmarked for Curphey. In 1909 Nora renewed her demand for a divorce. Mellon sought middle ground with a separation. He offered to provide Nora with the income from a $600,000 trust fund as well as an initial payment of $250,000. In 1910, things came to a head. Mellon moved out and filed for divorce on grounds of adultery.

The McMullen family, including Nora’s mother, were on Mellon’s side. In Pennsylvania, however, divorce on grounds of adultery called for a jury trial with all the risks of an unfavorable verdict and adverse publicity. And the Mellon divorce would provide enough scandal to fill a year’s worth of National Enquirer covers.

Mellon hired an army of operatives spanning Europe for evidence to support the adultery charge. Through a combination of prior efforts on behalf of Nora and Curphey to cover their tracks, third-rate gumshoes and plain bad luck, he came up empty. Nora fought back. She poisoned the minds of Ailsa and Paul against their father and gave incendiary newspaper interviews.

In the end Mellon won a Pyrrhic victory. The children were to remain in Pittsburgh, with Nora allowed four months visiting rights. Mellon took the pain to his grave. Badly scarred, Ailsa and Paul suffered the most.

A national figure

Following the pattern set forth by the judge, Mellon sought political influence to further his business interests. With his empire playing out on the national stage, Mellon became one of if not the biggest donor to the Republican Party. In 1920, Pennsylvania’s senators, Philander Knox (a longtime confidant of Andrew) and Boise Penrose lobbied President-elect Harding to name Andrew secretary of the treasury. His great creative period as a businessman had ended 10 years earlier. The second-highest position in the cabinet would help fill the void in his life.

He resigned 63 directorships, and Dick Mellon became the go-to guy for all the Mellon enterprises, performing admirably. Andrew was only a phone call away, though, and the brothers frequently consulted. It was a different world then, and Andrew never hesitated to use his considerable influence to lobby Congress on behalf of Gulf Oil and Alcoa.

Andrew’s tenure at the Treasury from 1921-1932 spanned three presidents — Harding, Coolidge and Hoover — and was surpassed in length only by Albert Gallatin. When Coolidge declined to run in 1928, there was talk of Mellon for President. The country was riding a floodtide of prosperity. The world’s preeminent financier, both private and public, was at the helm. The Mellon presidential movement never got off the ground, though, and it’s doubtful he had much interest. At 73 he was too old, and one can hardly imagine Mellon on the stump like Nelson Rockefeller at Coney Island, pressing the flesh in one hand while munching a hot dog with the other: “Hi ya fella.” It was not to be.

Mellon’s tenure at the Treasury earned him the reputation as the best Secretary since Alexander Hamilton. The times were right for Mellon, and Mellon was right for the times. Calvin Coolidge famously proclaimed: “The business of America is business.” Spending was cut, taxes were cut and surpluses abounded; America and Andrew Mellon had become banker to the world. The 1929 crash and the Great Depression left Mellon at sea, with the Hoover administration foundering. What might have been a financial panic in the manner of 1893 or 1907 was dragged into worldwide depression by Europe. And Mellon had only old tools to deal with a new problem. His solution was what Hoover called the “liquidation school.” Mellon’s answer was to sell: “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmer, liquidate real estate.” Hoover eased him out in February of 1932 by naming him Ambassador to the Court of St. James.

A philanthropist is born

In the late 1890s, Frick introduced Andrew to art. His early purchases were inexpensive and undistinguished. In 1905, Mellon deepened his interest, spending some $400,000 on a variety of good art. With the Mellon fortune in full flower after 1920, Mellon accelerated his purchases, becoming the most important collector in the country. He purchased a dozen or so masters in a range of $200,000 to $500,000. With help, Mellon’s eye was getting better, and he drove a hard bargain. Mellon’s coup d’maître came with his purchase of 21 of the world’s greatest paintings from the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. The Soviets needed money and wanted to make a large deal quietly; Mellon was their man. The bag included Hals, Raphael, Van Eyck, Veronese, Rembrandt and Botticelli. Mellon continued to make major purchases until the year before his death in 1937.

During the ’20s Mellon was a symbol of all that was right about America. With the New Deal, however, he was politically crucified as the cause of all that was wrong. No sooner was Franklin D. Roosevelt in office than he recalled Mellon from Britain. The Justice Department then instituted a series of suits against Mellon for fraudulent underpayment of taxes. Mellon was put on trial simply for being Mellon, and Roosevelt was the guiding hand in the political theater. The Board of Tax Appeals finally exonerated Mellon in December of 1937, three months after his death.

After returning from Britain in 1933, Mellon crafted the gift of his art collection to the nation he had served. In a letter to Roosevelt, Mellon outlined the proposal. At a specific site on the Mall in Washington, D.C., Mellon would erect at his expense a repository for his collection and for future additions to be called the National Gallery. He insisted that the gallery not bear his name; this was a significant act of self-effacement but only in part. As the National Gallery, other major donors would augment the riches of the gallery far beyond Mellon’s seeding gift. His legacy would be made all the more powerful and enduring.

The trustees were to be named by Mellon and their successors co-opted by his initial board, ensuring in a sense Mellon control beyond the grave. His offer was subject to no political compromise; it was take it or leave it, period. At a meeting with Roosevelt, the deal was formally struck and soon ratified by the Congress. Returning from a very pleasant meeting with the man who had put him on trial for the excesses of the ’20s, Mellon remarked to an associate: “What a wonderfully attractive man the president is.” Thus at a stroke Mellon gave witness to Roosevelt’s infinite capacity to charm, and no less to his own humanity.

For a man whose talents were remarkably unbalanced, Andrew Mellon’s achievements were stunning. As a financier, he was second only to J.P. Morgan. As an industrialist he ranks with Carnegie, Ford and Rockefeller. He gave birth to not one, but five Fortune 500 companies, plus a score of enterprises, each of which could be the basis for an enduring family fortune. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation is one of the nation’s largest, with assets exceeding $4 billion. Indirectly, through bequests of his brother Dick and Dick’s son Richard King Mellon, billions more have been provided.

Despite this, there was a sadness in his life. Are the origins to be found when he ignored Nora McMullen’s prophetic warnings against their marriage? Or was it far earlier, when the little boy accepted his father’s charge to shoulder the burden of his all-consuming dynastic vision?