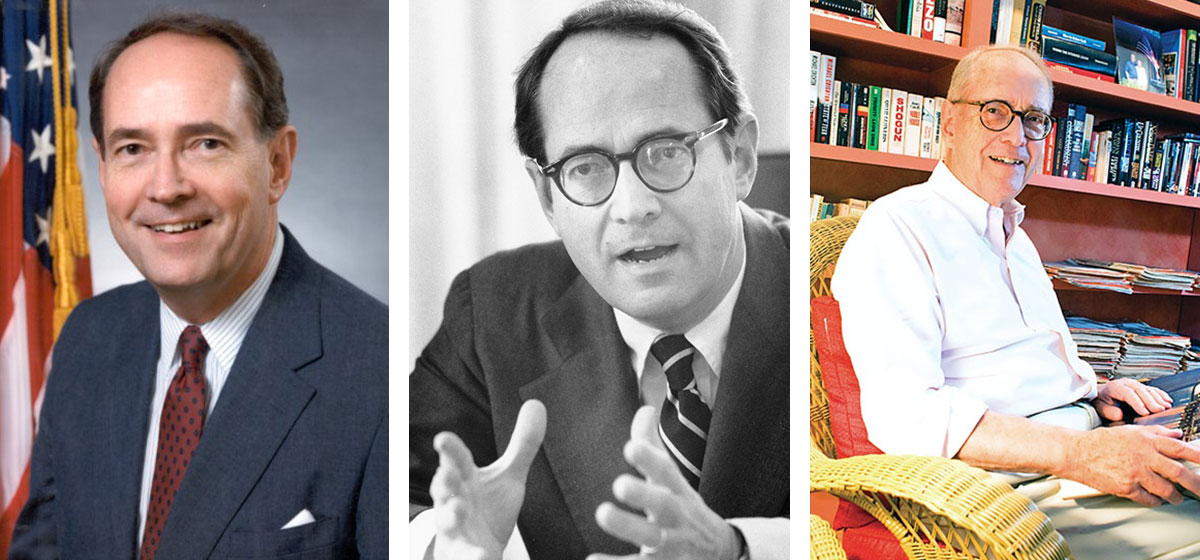

A Reflection on the Life of Dick Thornburgh

Written by his son David Bradford Thornburgh, read by his granddaughter Blair Elizabeth Thornburgh at Shadyside Presbyterian Church on Jan. 16, 2021.

It’s my great honor to read the following reflection about the life of my grandfather, as written by my father, David.

In my dad’s words, about his:

I’m sure all of us have been overwhelmed by the hundreds of condolences we have received since Dec. 31. Those public remembrances testify to the enormous good that this remarkable man brought to the lives of so many, most of whom we never knew and may never meet.

But now this is a time for us gathered in this chapel—those who knew him best and loved him most—to reflect on his life, and to remember and cherish what made him such a special man in our lives. I hope these words will be of comfort, and I know they will be just the beginning of our shared reflections, which will continue to grow and which will inspire us our entire lives, and, we hope, will inspire the lives of our children and grandchildren as well.

Dad was the star of his own Frank Capra movie. Take “It’s a Wonderful Life,” add “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” top off with “You Can’t Take it With You,” and there you have the life of Dick Thornburgh. And, of course, who other than Jimmy Stewart (except maybe Gregory Peck or Henry Fonda) could be cast to play the starring role?

It’s a familiar story to most of us, but it’s a great story, and great stories should always be told and retold. Like many great stories, it’s somewhat improbable. Dad often said that his Mercersburg and Yale classmates were utterly mystified as to how the Dick Thornburgh they knew became the Dick Thornburgh they read about and admired. He imagined them rummaging around for their old yearbooks to make sure they had gotten the name right, and that he was in fact the same guy.

David McCullough, one of Dad’s favorite historians, has noted that in leadership, character is everything. In fact, to the ancient Greeks, character is destiny. Doris Kearns Goodwin, another favorite, further observed that great leaders are defined by an unusual combination of great confidence and great humility.

So how did Dick Thornburgh gain the confidence and the humility to become the man he became?

Clarence, help us out.

Dick Thornburgh was born at home, in Rosslyn Farms on July 16, 1932. In that bucolic community, Dick lived the Great American Childhood. Taught in a four room schoolhouse, he made lifelong friends, participated actively in the life of the community, and tried to stay out of trouble—witness that small “incident” involving a payment of Girl Scout dues that went astray after being placed in Dick’s care. (An illicit purchase of candy ensued.) Eleven years younger than his next youngest sibling, Dad grew up almost as an only child. Besides his small group of great friends, he lived in a world bounded by books, the Sporting News, All Star Baseball, and Life magazines. An enthusiastic but limited athlete, he became a rabid fan of all sports, but primarily of his Pittsburgh Pirates. He thought he might be a sportswriter one day.

Dad left the protected cocoon of Rosslyn Farms to enter Carnegie High School. Carnegie was a rough and tumble steel town, and its high school was not exactly known for the rigor of its academics. While earning straight As, but perhaps eager to stand out in other ways and—despite an accidental and fleeting wrestling triumph—not finding that opportunity in sports, Dick ended up, it seems, goofing off a lot. Probably after a few stern talking-tos by his father, he was packed off to Mercersburg Academy where, his parents fervently hoped, a change of scenery and peers would help him focus on his studies. That was not to be, as Dick spent a considerable amount of time “walking guard” early Saturday mornings in order to work off the demerits earned by his mischief.

On New Year’s Eve 1948, Dick met the first love of his life, Virginia Kendall Hooton. A vivacious, popular and warm young woman who could play the jazz piano stylings of Errol Garner and Ralph Sutton by ear, she and Dick became inseparable. After he headed to Yale and she enrolled at Connecticut College, they spent many weekends together in New Haven or, on occasion, on trips to New York City to sample the nightlife. In fact, it seems Dick’s extracurricular activities—his acting pursuits, flicking out at the movies with his “Dirty Eight” buddies, yukking it up at the Fence Club—left little time for his curricular life. Without much reflection, he had chosen to major in civil engineering, a field for which he had neither aptitude nor interest, but which his father, grandfather, great-grandfather, brother and two uncles had all pursued. After his father died suddenly in December of his sophomore year, Dick’s grades tumbled to the point where he faced the equivalent of “double secret probation,” and he was banned from extracurricular activities. Smart, witty and charming to those who knew him, let’s just say that academically he occupied that part of his class which “makes the top of the class possible.”

But in his senior year he made a fortuitous choice. Perhaps hoping to avoid a seemingly inevitable career in the family profession of civil engineering, he enrolled in a course on business law. It turned out to be one of his favorite classes, where he finally excelled. When it came time for him to graduate in 1954, he applied to and was accepted at Pitt Law School.

Instead of constructing bridges, tunnels, and roads, Dick would now be constructing cases.

A year later he and Ginny Hooton were married and, when he graduated in 1957 with an impressive academic record, he accepted a position as staff counsel for the Alcoa Corporation in Pittsburgh. Soon after, John was born, and then thirteen months later David, and then, sixteen months after that, Peter came along. In 1959 Dad left Alcoa and joined the Kirkpatrick & Lockhart law firm. In the spring of 1960, his life couldn’t have felt more complete. He and Ginny were as content as a young couple with three little “chicks” could be.

It’s here, of course, that fate intervenes. I remember trying to imagine, when I turned 27, what it possibly could have been like to get a phone call informing me that my beloved wife had been killed in a car accident, that my dear little boys had been seriously injured. Novelists call it the Dark Night of the Soul, when fate tests faith and brings to the fore those most fundamental questions of human existence: How could this have happened to me? What is now the meaning of my life? Where do I go from here? This was George Bailey’s moment of despair and decision on that snowy bridge on Christmas Eve.

Sometimes fate answers her own questions. And so it was that, as an extra man at a wedding in April 1963, Dad met an outgoing, spunky 23-year-old named Ginny Judson, who immediately stole his heart. Her “amazing grace” rescued him and revived him, put him on course and gave new meaning and purpose to his life. To say that theirs is one of the world’s great love stories doesn’t begin to do it justice. Quite different from each other, their souls nevertheless completed each other’s. He brought her insight, intellect and perspective, and she brought him confidence, focus and purpose. These two should, and I believe, will go down in history as one of the great couples of all time. With the two of them, one plus one truly equaled multiples of three.

After their whirlwind courtship and marriage in October 1963, together they plunged into the formidable but rewarding task of raising their young family, and particularly caring and advocating for Peter. Their world was changing in other ways. Six weeks after their marriage, President Kennedy was shot, which ushered in a period of intense social and political upheaval. Republican Barry Goldwater’s crushing defeat in the Presidential election of 1964 jolted Dad into action. Raised as a Wendell Wilkie Republican, he was interested in politics, but had never been particularly active. 1964 changed all that. In a letter to the Post-Gazette, written the day after the election, Dick decried the “infusion into our party of a brand of fanatic political extremism which rallied every right-wing fringe group… The time is now, Republicans. We must, beginning today, start the job of rebuilding our party… Let us be done with the lunatic fringe. Let us look instead for inspiration to the principles of Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt and Dwight Eisenhower which have made our party great.”

With Mom by his side, by the time Bill came along in 1966 he had already embarked on a lifelong journey of service to his beloved nation and to the world. In that brief six year period, from 1960 to 1966, Dick Thornburgh had suffered great loss, and had found great love. He had gained the confidence and the humility that Kearns Goodwin describes. He had found his calling, which the theologian Frederick Beuchner described simply as “the place God calls you to… where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.”

So there you have it: My version of the story of how my dad became Dick Thornburgh. But of course there’s so much more, so many stories and so many details. He was a great storyteller and we honor his life by telling and retelling his stories. His story is now our story, and ours, his.

Great stories, of course, are also told with great details. Here are a few of my favorite things about my dad, a man of extraordinary interests and abilities. Pick one or two that you didn’t know, or maybe didn’t appreciate, or pick from your own. So now, for Dick Thornburgh, watch Rocky and Bullwinkle. Look up a word you don’t know. Listen to Shorty Nadine on a Jazz at the Philharmonic album. Read John Updike’s “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu”. Watch the 7th game of the 1960 World Series. Practice speaking as Count Dracula. Watch “The Third Man.” Listen to Sha Na Na. Make a note, with a red felt-tip pen, of the next typo you encounter. Sing “Mack the Knife.” Listen to Tammy Wynette. Read Jacques Barzun. Listen to Errol Garner’s “Concert by the Sea.” And finally, of course, watch a Frank Capra movie. Or three.

I hope always to hear my dad’s voice whenever I need it most. To be reminded to do the right thing, and to do it right. To remember to bend down and talk to the little one, or to the person using a chair, at their level and on their terms. To show understanding, to share gratitude and to offer the important small kindnesses that people always remember. As written in his favorite Bible verse, Micah 6:8, Dick Thornburgh did justice, he loved kindness, and now he walks humbly with our God.