A Bold Look at Race Through Art at the Carnegie Museum of Art

When Vogue lauded “20 / 20: The Studio Museum of Harlem and Carnegie Museum of Art” as the most important art show in America, they guaranteed a critical response. Setting aside the hyperbole, the magazine established race as the context for viewing and thinking about the exhibition, stating that “as monuments to Confederate generals come crashing down in the South, and white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and those who champion their values keep a terrifying grip on the media,” the exhibition offers “a dialogue on the importance of art during times of political and social change.” Amanda Hunt, former associate curator at the Studio Museum even called it “an unprecedented exhibition” “about America and its current state, about its history and the complexity of that history, and especially how it has specifically impacted communities of color over time,” while the Carnegie’s curator Eric Crosby was more measured, writing that the show (which runs through Dec. 31) couldn’t possibly cover all aspects of today’s national conversation.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”216″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

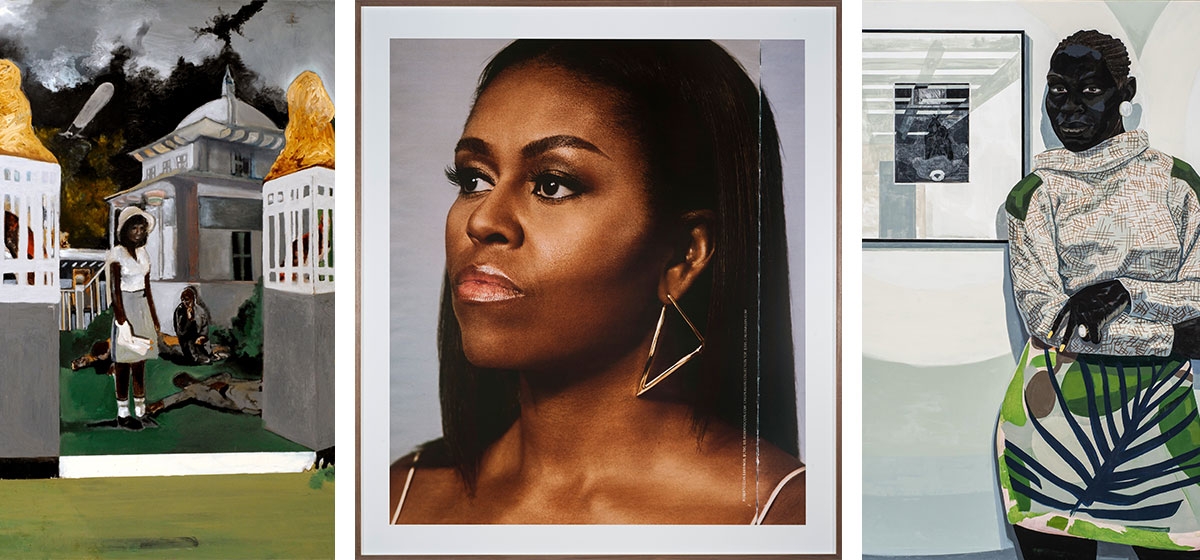

What started as a simple premise, combining selections from the collections of two very different museums—one encyclopedic with an emphasis on art of our times and the other dedicated to artists of African descent—had been blown up into something else. The curators brought together works made in the last 100 years by 40 artists, 20 from each museum, and arranged them in six categories: A More Perfect Union about democratic ideals, Working Thought about histories of labor and economics, American Landscape about social and physical landscapes, Documenting Black Life, Shrine for the Spirit about spiritual introspections, and Forms of Resistance. Whew. Painting a picture with such a wide brush might have made sense because of the diverse works available from each museum, but no exhibition can cover so much territory, and “20 / 20” can seem confusing, distracting from the pure pleasure of seeing work by so many people of color in the Carnegie at one time.

Crosby and Hunt opened the exhibition with a small, unassuming painting by a self-taught artist. Horace Pippin’s “Abe Lincoln’s First Book” (1944) features the future president in a white shirt reaching into a dark background for a book, an image they feel is full of hope, perhaps signaled by the single candle. The president who liberated the slaves is shown as an educated man, reaching for knowledge that perhaps led him to reassess the practice of owning, buying, and selling human beings as he sought to reinforce or reinstate the more perfect union promised in the constitution and referenced by the curators as the starting point for the show.

Coming after World War II, Pippin’s painting seems much more enigmatic, perhaps suggesting that emancipation was difficult to achieve and that 80 years later, there was still serious racial inequality in the country. The artist himself served in the first world war, suffering serious injury to his right arm and most likely experiencing the mistreatment of black soldiers by the American military. In his last series of paintings, “The Holy Mountain” (1944-46), he situated a peaceable kingdom inspired arrangement of animals in a landscape, but this calm is fractured by the crosses, soldiers, and lynchings hiding in the dark background. Perhaps that contrast between peace and war is also the underlying theme of Pippin’s portrait, a reality check about promises made and the difficulty and slow pace of change. Even the curators echo this disappointment by referencing Barack Obama’s 2008 speech about race when he reused the idea of a hoped for more perfect union.

A similar ambiguity and questioning characterize the brilliant photograph by Gordon Parks of a black man’s head silhouetted against a light background as it emerges from a manhole in a deserted location. Part of a 1952 essay for LIFE to illustrate the bestselling “Invisible Man” by his friend Ralph Ellison, “Emerging Man, Harlem, NY,” refers to a scene cut from the book in which the black protagonist escapes from a hospital through underground tunnels. As a single image, removed from that context, it gains new meanings; the man could be one of many invisible city workers, perhaps part of the great migration. Is he emerging from the nether regions, pulling himself up by his own strength or is he holding on for dear life, about to slip back down into the darkness? Is this a sign of respect for honest work or a reference to Ellison’s view of Harlem, a cultural capital within a city of culture, as “the scene and symbol of the Negro’s perpetual alienation in the land of his birth.” Perhaps the answer can be found in the nearby work of Glenn Ligon that contains a repeated stenciling of a phrase written by Jean Genet about blacks in America: “They are the ink that gives the white page a meaning.” Changing Genet’s pronoun to “we,” Ligon presents a proud and powerful voice.

The two works by Pippin and Parks placed at the beginning of the exhibition were made only six years apart, at a time when segregation was still in place and the civil rights act was more than a decade away. The U.S. was in the throes of the red scare with McCarthy’s activities dominating the news. Concentrating on searching out communist spies, the Wisconsin senator questioned very few Negroes because, in fact, few were in positions of power. Langston Hughes, a leader of the Harlem Renaissance, a renowned poet, and a social activist, was one of the few called to testify. Starting his remarks with “I was born a Negro,” Hughes went on to speak about things denied him because of his race. In his poem “I Too,” written in the 1920s, Hughes, like Ligon, asserts his identity as an American, writing that despite racism, he too can “sing America,” and he too “[is] America.”

The layered, and at times ambiguous, ideas raised by works like these continue throughout the exhibition, and there is a lot of star power here with some of the best African American artists. A grouping of cold, hard, industrial sculptures that speak about the lynching of black men by Melvin Edwards sit uncomfortably beside the tar-covered faces of black prisoners by Titus Kaphar; Kori Newkirk’s beaded curtain inspired by Venus and Serena Williams’ hair can be compared to the augmented ads for black hair products by Ellen Gallagher or the conceptual work of Lorna Simpson. The photographs of James Van Der Zee, Teenie Harris, Zoe Straus, Collier Schor, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Lyle Ashton Harris offer a range of subjects and intentions, though it might have been nice to see them all in one place in the galleries. The artist list, including a few works by white artists, is impressive, almost making us forget the absence of figures such as Betye or Allison Saar, Faith Ringgold or Wangechi Mutu.

There is a powerful piece by Kara Walker from the Carnegie’s collection that is rarely seen for conservation reasons. Walker, a mature artist sure of herself and her mediums, brave and courageous in her beliefs, has become a lightning rod for any representation of race, both praised and criticized by African Americans while practically universally loved by white viewers. These prints, part of a larger series, mimic her silhouette work; the simplicity of the black on white imagery is direct and pointed, like a concrete illustration of Ligon’s black ink giving the expansive white field meaning. The horror of slavery cannot be escaped, the four “incidents” building the evidence, witnessing the travails as we read and fill in her narrative. Her title, “Emancipation Approximation” hints that while emancipation was proclaimed, perhaps it wasn’t fully achieved, and we are still fighting injustice and inequality even while we struggle to deal with the embarrassing history of slavery in our country.

In a recent review of Walker’s work at a New York gallery, Jerry Saltz claims that one of the works on view in the show there is perhaps the best painting about America. Just adding that word, perhaps, admits the possibility of other opinions and changing ideas over time, unlike Vogue’s bombastic headline. While it is a challenging and engaging exhibition, and hopefully just the beginning of adding representation of, about, and by people of color to the Carnegie’s collection, 20/20 is not only not the most important art show in America right now, it wasn’t even the best show about race in Pittsburgh when it opened. That honor belonged to “Oaths and Epithets: Works by Sonya Clark” at the Society for Contemporary Craft, even though it is probably unfair to compare a one-person show with a group exhibition limited to works owned by two museums, with a few additions from private collections. But for all of its faults, the Carnegie’s exhibition is a giant step in the right direction. It reinforces their purchase of a work by the acclaimed master of narrative painting, Kerry James Marshall. His black-skinned protagonist stands in a museum, signaling not only a presence but a sense of belonging.

Any discussion of race is fraught with so many difficulties that it can be practically impossible to utter a single word, but the Carnegie has given visibility to artists whose work has rarely been seen in Pittsburgh. In Saltz’s review of the Kara Walker show, he quotes James Baldwin who once said “no true account really of black life can be held, can be contained, in the American vocabulary.” “20 / 20” makes a case for the possibility of developing a visual vocabulary that at least attempts to do exactly that.