Robert Taylor: Demanding Coach

James H. Morris is a retired professor of computer science and dean of the West Coast campus of Carnegie Mellon University. In a series of blogs for Pittsburgh Quarterly he writes about some of the computing pioneers he encountered during his career.

As I struggled with the rigors of being an assistant professor at University of California, Berkeley and was approaching fatherhood, I read a Rolling Stone article about Xerox’s new Palo Alto Research Center, called PARC. Xerox wanted the center to design the office of the future.

Robert Taylor, a former program director at the U.S. Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, was a manager there. He had hired many of the computer science Ph.D.s whose research he had supported. There were former child prodigies, future Turing Award winners, and future Silicon Valley multi-millionaires—all under 40. One of them was Alan Kay, who had been a Quiz Kid on the radio in the 1950’s. He said, “This is really a frightening group, by far the best I know of as far as talent and creativity. The people here all have track records and are used to dealing lightning with both hands.” Even though I could barely deal lightning with one hand, I wangled an interview with Taylor and his gang.

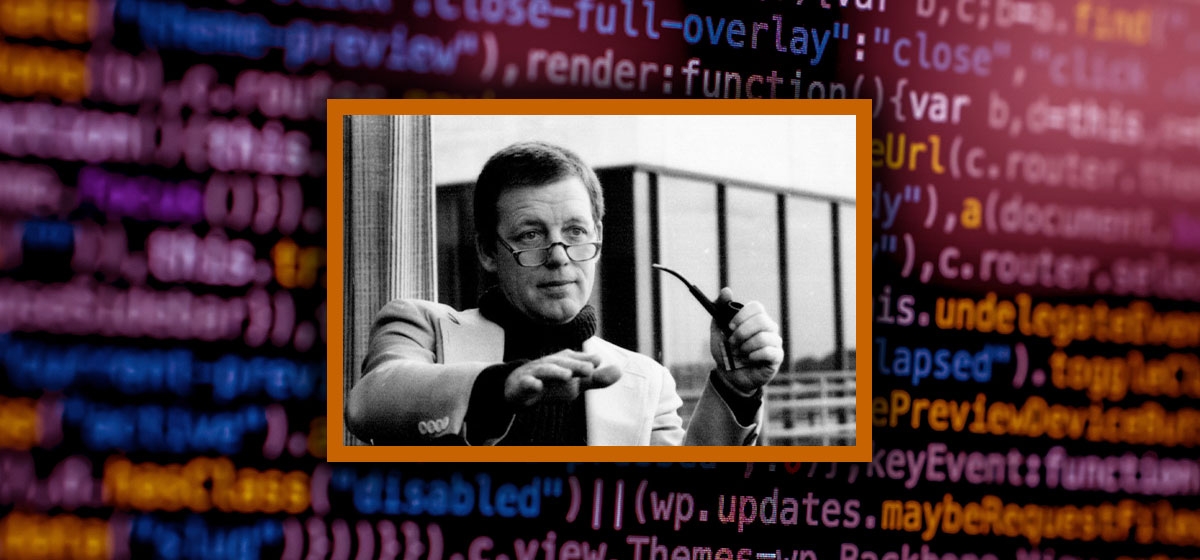

The Svengali-like Robert Taylor fixed his intense blue eyes on me and told me he wanted PARC to be as great as Bell Labs. That was ridiculously ambitious. Bell Labs housed Nobel Prize winners and had invented the transistor, cell phone and the UNIX software system.

He was more interested in why I did things than in what I’d done. He asked what made me tick. I blurted out that I wanted computers to help people rather than governments and corporations, forgetting that Xerox was a corporation. He must have liked that, because I got a job, even after my technical presentation to the assembled geniuses ended with them gleefully uncovering a flaw.

Bob was born in Texas and was adopted as an infant. In high school, Bob had been a competitive athlete and a part-time cowboy. He once intentionally antagonized a Brahman bull into throwing him off its back. He’d entered college at 16, served in the Navy, gotten degrees in psychology, but never bothered with a Ph.D. In his own words, he’d been to a few county fairs.

While I admired the brilliance of my Ph.D. colleagues, I was entranced by Bob’s leadership skill. He found herding computer geeks easier than herding cattle. Most of our egos were concerned with who was smarter. Bob’s considerable ego was somewhere else. He was like a football coach who selected and exploited talent to win games. He particularly wanted to outdo IBM.

He believed competition created excellence and encouraged us to argue about technical issues. However, he required each side of an issue to give coherent descriptions of the other side’s view. He never competed with us and allowed us to take all the credit for our technical achievements. However, in the end, his vision of the computer as a personal, interactive communication platform emerged. We invented the networked personal computer and called it the Alto.

Here is a picture of the Alto computer. When I showed the one in my office to my mother-in-law she thought it was a television on top of an air conditioner. I had to tell her it cost $20,000 to impress her.

Xerox donated complete Alto systems to Stanford University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Carnegie Mellon University. True to form, MIT ignored it, Stanford spun off SUN Microsystems to commercialize it, and Carnegie Mellon did research on it.

While Bob was a joy to work for, he was hell on organizations that employed him. His competitive instincts made him attack all the units around him and belabor his superiors for more resources. Many people in Xerox were relieved when he left to start a research group for the Digital Equipment Corporation. He once tried to get me to take over a Digital Equipment research lab adjacent to his, but I knew better than to compete with him. Later, he browbeat Digital into giving my startup company, MAYA Design, a contract.

In retirement, Bob became a curmudgeon, rarely leaving his house in the hills above Silicon Valley. He complained about the many people claiming to be fathers of the Internet when, in fact, he had initiated the DARPA research program that led to it. When he won the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers’ John von Neumann Medal and the Presidential Medal of Freedom he refused to travel to Washington, DC to accept them. He even suggested that Bill Clinton drop off the latter while visiting his daughter, Chelsea, at Stanford.

A few days before he died he sent all of us email thanking us for being his friends. It ended with his signature goodbye, “Write if you get work.” Bob’s obituary appeared on the front page of the New York Times, above the fold.