August Wilson and the Joe Louis-Billy Conn Title Rematch

Pulitzer prize-winning dramatist and Pittsburgh native August Wilson dramatized the modern history of African-Americans in 10 plays, often called the Pittsburgh cycle, for each decade of the 20th century.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”144″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

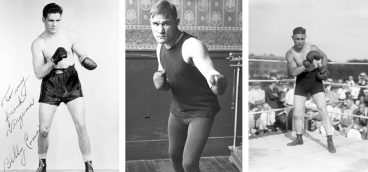

In “Seven Guitars,” set in the Hill District in the 1940s, the key historical moment comes when his characters gather to listen on the radio to a heavyweight championship rematch between Joe Louis and Billy Conn.

In May 1941, Conn, who grew up in East Liberty, lost one of the most memorable heavyweight championship bouts in boxing history when he was knocked out in the 13th round after outboxing Louis throughout the fight. When Conn broke his hand in a fist-fight with his father-in-law just before a scheduled rematch with Louis, he had to wait until after the war for another shot at the heavyweight title.

In June 1946, Billy Conn finally had his rematch, but he wasn’t the same fighter who had nearly defeated Louis five years earlier. In “Seven Guitars,” Wilson’s characters listen to legendary broadcaster Don Dunphy describe Louis’s eighth-round knockout of Conn: “A hard right, a left, and a straight right that knocks Conn down. He’s flat on his back! His eyes are closed! It’s all over! It’s all over!”

In the first half of the 20th century, boxing was as popular as baseball for those living in Pittsburgh’s ethnic and minority neighborhoods. A few years after the Pirates gave Pittsburgh its first professional championship with its 1909 World Series victory, two area boxers made Pittsburgh the city of champions. In 1913, New Castle’s George Chip challenged and knocked out Pittsburgh native and middleweight champion Fred Klaus. Chip and Klaus were just the beginning of a long line of boxing champions with close ties to Pittsburgh and environs.

“The Pittsburgh Windmill” Harry Greb, and “The Croat Comet” Fritzi Zivic headed an impressive group of area boxing champions that included Monaca’s Teddy Yarosz, Farrell’s Billy Soose, and Jackie Wilson, who was born in South Carolina but grew up and fought in Pittsburgh. In 1941, the year of the first Joe Louis-Billy Conn title fight, Conn was boxing’s light-heavyweight champion, Soose held the middle-weight title and Zivic was the welterweight champion.

My father loved boxing and let me tag along when he walked to Kalka’s, his favorite beer joint on Pittsburgh’s South Side, to take in the Pabst Blue Ribbon Bouts on Wednesday nights and the Friday fights on the Gillette Cavalcade of Sports. I sat on a bar stool and watched boxing legends from flyweight Wille Pep and welterweight Kid Gavilan to light-heavyweight Archie Moore and heavyweight Jersey Joe Walcott.

My father, like most of city’s working class, rooted for “The Pittsburgh Kid,” Billy Conn, in his rematch with Louis, but that wasn’t the case for those living in the Hill District. In “Seven Guitars,” August Wilson’s characters gather around the radio to root for “The Brown Bomber.” When Louis knocks out Conn, they celebrate by gathering in a circle and dancing the “Joe Louis Shuffle.”

After the celebration, Floyd “Schoolboy” Barton, a talented blues guitarist, marvels that Louis, described as “The Mighty Mighty Black Man” earlier in the play, can “beat up a white man in front of a hundred thousand people and they give him a million dollars. If I go out there and punch a white man in the mouth, they give me five years.” Barton, who just spent 90 days in the workhouse, is told that “Louis got a license and you don’t. He’s registered with the government and you ain’t.”

The “licensed” Joe Louis knocked out Billy Conn in their title rematch, but his victory, while a source of pride for African-Americans, didn’t knock down racial barriers in the post-war America of the 1940s, even for Louis. Exploited by white managers and promoters, he paid a heavy price for his success. After his retirement as undefeated heavyweight champion, the IRS hounded Louis for delinquent taxes. He had to endure humiliating defeats in a boxing ring that he once dominated in a futile effort to pay off his debt.

In “Seven Guitars” Floyd Barton believes he has the talent and toughness to become “the Mighty, Mighty Black Man,” but his desperate effort to overcome the bigotry and injustice that surround him lead only to his violent death. Looming over his tragedy is the figure of Joe Louis, a hero to African-Americans but also a victim of the same forces of bigotry and injustice that would destroy Barton, provoke the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, and still haunt America.